As the smoke begins to clear on COVID and we gain more perspective for where radio has been as an industry and where we’re headed, one thing is clear:

The path we were on in 2019 has been disrupted by the pandemic. You can make the case that many of the trends that were in motion accelerated during the many weeks and months of lockdowns, mask orders, work from home, and social distancing.

But it runs deeper than that. COVID forces us to take stock of our lives, our careers, our life philosophy, and our purpose, unlike anything we’ve experienced before. Aside from the fans in the street for the “Free Britney” movement, most of us now have a lot on our plates as we consider what’s important to us versus the sideshows in our lives.

From the standpoint of working in radio at this pivotal moment in time, it is certainly a time of reflection; of determining what matters to our careers, our mission at work, and what we’re trying to accomplish. I’ve been doing this in one form or another for 45 years, and I cannot think of another point on the curve when everything has felt so up in the air as it does now.

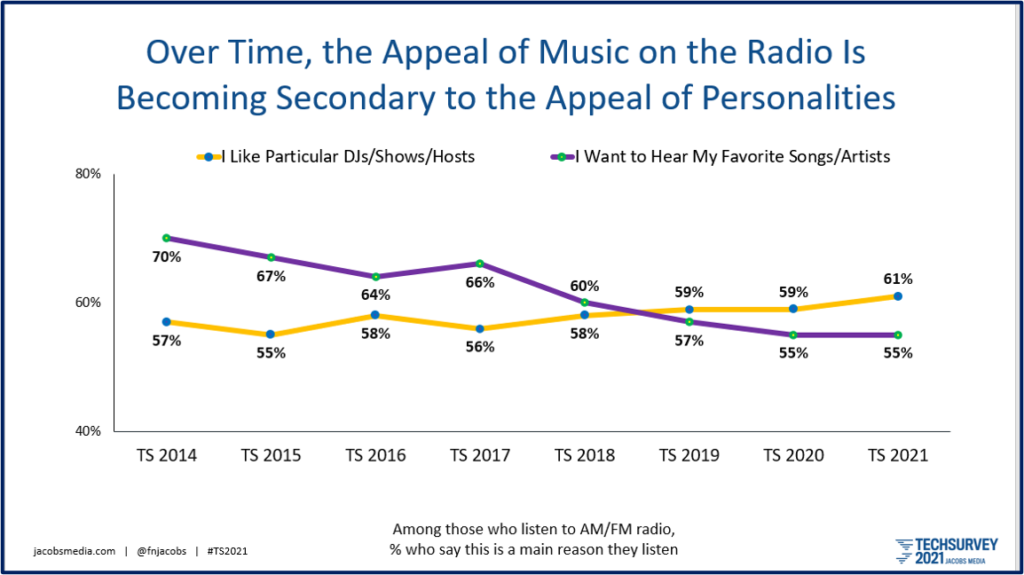

My hope is that our Techsurveys – especially the one we conducted earlier in 2021, subtitled “Radio in the Year of COVID” – have helped the industry prioritize what matters most and what needs our attention now – and what can wait. As you very likely have seen in myriad presentations I’ve conducted or via our free online resources, the division between the import of personalities vis-à-vis music has never been wider.

When we examine the key drivers responsible for broadcast radio listening, we can see the trajectory of these two trendlines moving in opposite directions on the longitudinal chart below.

Music has become a commodity, thanks to the many playlist services now available, coupled with the way so many stations are unimaginatively mailing their music in. Conversely, on-air personalities have gained in importance as the two lines crossed back in 2019:

These findings were brilliantly echoed by Mike McVay in yesterday’s Radio Ink in a column simply titled “Why On-Air Talent Matter.” That Mike even had to write this piece in 2021 speaks volumes about how some companies, clusters, and stations have lost their compass.

Mike’s think piece is must-reading, if nothing else to remind those you work with or work for about how one of the savviest, most experienced industry veterans views your industry.

Along the way, Mike issues some fundamental pointers about personality preparedness, crisis coverage, and the realization that many digital services are now pursuing the personality route. If you read this blog regularly, you’ve no doubt encountered what one industry maven calls “Fred’s four-alarm fires.”

the personality route. If you read this blog regularly, you’ve no doubt encountered what one industry maven calls “Fred’s four-alarm fires.”

Sorry all, but the mandate for every station to have, as Mike puts it, “at least one radio star” is now table stakes.

And as he reminds us, “If you have a star, keep them.”

That’s precisely what I want to highlight in bright yellow in today’s post –the art of retaining your best personality (or personalities). And again from McVay, “That’s easier than trying to find a new star.”

Along the way I’ve learned the easiest thing to do is fire the morning show or the nighttime host. The hardest part is replacing them with talent that can improve the station and contribute to brand growth.

So often, stations (and companies) make talent cuts, only to have no Plan B or to assume that anything would be better than who’s on the air now. Most of the time, that’s a bad assumption.

Rather than suggesting that great talent is replaceable, my point (and McVay’s) is that your operation will be more stable, marketable to clients, and able to survive the inevitable ups and downs when you have a star talent – or two.

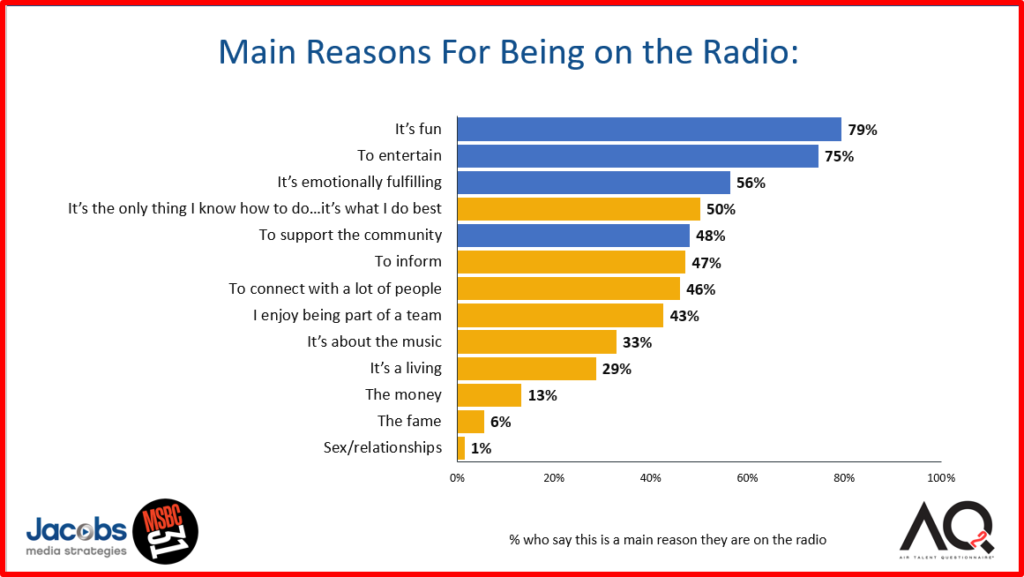

In so many ways, it is about the environment at the station level that is the difference-maker. And to that end, let’s go back to our study of more than 1,000 personalities in the U.S. from 2019. We asked them to give us their main reasons why they chose to don the headphones and crack the mic. And it turns out so much has to do with personal satisfaction – it’s fun, it’s emotionally fulfilling, it is wonderful to entertain and to serve communities:

So, leapfrogging off Mike’s premise, how can station management best interact and connect with its star talent – especially if things get a little gnarly, as they often do.

In the new issue of Fast Company, author and speaker Harvey Deutschendorf writes a useful set of guidelines for dealing with the inevitable dust-ups with your rock star air staffers;

“7 steps to take when a star employee disengages”

Not all of his tips resonate with the challenges posed by retaining on-air talent, but several do. I’ve included them below, mashed up with a few of mine. As always, the “comments” section below is a great place to expand this list.

Don’t let it slide – Oftentimes, things start slipping downhill well before the crash. You hear the phrase a lot when a star decides to leave the station, “Well, he’s been unhappy for a long time.” Yet, managers and programmers – fearful of rocking the boat – let problems fester by neglecting them.

Seldom do things somehow work out by themselves without some form of management intervention. And in most situations, there’s a “point of no return” when things get so bad, they’re not repairable.

Proactivity is an important but brave path that great managers pursue before it’s too late, and a franchise player decides to leave the coop.

Great managers don’t make assumptions about the cause. They know station scuttlebutt rarely explains the root problem, because it’s based more on gossip and rumor than facts.

Get to to the bottom of it.

And that means speaking directly to talent, macheting your way through the crap and innuendo to meet the speed bump with your star talent head on.

Sometimes, the kerfuffle (or a more serious problem) has to with a personal issue outside the station – I call them “off-the-field problems” – you might not suspect. Find out before you start drawing conclusions that are off-base.

At these moments, management can often help out with a personal issue or dilemma, earning points with an appreciative star personality.

Be firm but sensitive – As Deutschendorf acknowledges, this is where EI – emotional intelligence – plays an out-sized role. Who knows what has talent all knotted up? As a manager, you have more knowledge and facts than they do about what’s going on in the industry, your company, or inside the station.

A key here is to focus on what has worked historically in the talent/station relationship, using that as the jumping off point. Tell them how you (and the company) feel about them, their role, and their contribution. Bring up a past victory that was meaningful to your star that illustrates the strength of your relationship.

At the end of the day – or the contract, as the case may be – there may be only so much you can do to remedy a situation or to meet a demand. Being straightforward and honest is preferable to the kabuki dance where nothing is solidified or solves the actual problem.

![]() Practice good listening – In our multi-tasking world, managers have a tendency to perceive things in their own terms, spending too much time focused on what’s important to them.

Practice good listening – In our multi-tasking world, managers have a tendency to perceive things in their own terms, spending too much time focused on what’s important to them.

You’re on a fact-finding mission. Ask clear questions, and then get out of the way. Deutschendorf recommends repeating some of their key points to achieve consensus that you heard them correctly and to achieve common agreement.

Another piece of good advice? Smart use of “dead air.” Use moments of silence in the conversation to your advantage by not butting in when things hit a lull. Most people feel compelled to fill in the conversational space. Instead, give the discussion a pause and just wait – that’s where you often get the gold.

Don’t do it over Zoom or the phone – Just a few weeks ago, you had no choice. But with each passing day, the opportunity![]() to look one another in the eye – sharing the same space – grows. Take advantage of it.

to look one another in the eye – sharing the same space – grows. Take advantage of it.

Zoom, GoToMeeting, Facetime, Microsoft Teams, Slack, and other communication tools were essential, especially during the dark days of COVID. They facilitated staff meetings, aircheck sessions, staff happy hours, and check-in sessions. But for a real conversation at a critical time, do it in person.

A neutral space – not your office – is an even better idea. Getting away from the pressure cooker for an hour might be good for both of you.

Treat them like a member of the team – Oftentimes, management pigeon-holes talent as simply the golden voice over the airwaves. But the true stars see, hear, and feel their audiences in ways programmers, corporate execs, and consultants cannot. Ask them what they’re hearing – not just when they listen in other dayparts but on other stations, on the phones, and inside their friend and family circles.

On the one hand, they may not be paying much attention to any of these things. But the superstars don’t just focus on their shows and their IRAs – they think it through and often bring a different perspective along that is worth hearing.

Share “intelligence” with them – Of course, not everything in rating books or in a station’s proprietary research should be shared with them. But some of it can.  And most on-air talent appreciate what actually goes into the strategic process. They may not concur with every aspect of your game plan, but at least they can understand why you do the things you do.

And most on-air talent appreciate what actually goes into the strategic process. They may not concur with every aspect of your game plan, but at least they can understand why you do the things you do.

Like giving them a chance to go backstage, seeing information not everyone is privy to can create a stronger connection. You can also sensitize them to the difficulty of your job, and how much goes into making those big decisions.

It can also be beneficial to expose your star (and the rest of the airstaff) to outside thinking – whether it’s someone from Nielsen, the consultant, a guest speaker. Make them smarter. They’ll respect you (and the company) as a result.

Don’t throw your company under the bus – As much of radio has become more top-down in recent years, there’s a tendency on the part of some programmers and managers to throw up their hands and blame their current course of action on corporate.

Commiserating with talent is usually the wrong path because it calls into question why you’re both working for the station/company in the first place. “You know how it is around here” will only get you so far, so avoid those moments where you admit you have little control.![]()

“I’m just following orders” does not sit well with talent, nor does it make you look good. When a mandate happens, try to own it or at least be able to explain the rationale behind it, rather than creating an us vs. them scenario.

When you start seriously negotiating on that next contract or even a personal appearance, the last thing you want to do is make the company the enemy.

You may not be able to affect change at the company level, but you can help build and reinforce the reputation that your station takes care of its talent, and treats them fairly. These days, that might be part of the difference that sets you apart. I have worked for some great programmers and general managers who were working for less-than-wonderful companies. But employees – including rock star talent – felt like they were working for local management – and not the evil corporate team a thousand miles away. Any manager can create a nurturing, compassionate, and engaged environment.

As we move away from 2020, and the radio broadcasting industry regains its equilibrium, the competitive pressure won’t go away. In fact, it will only intensify as more mega-players dive into the lucrative audio pool. Realizing what – and who – is important to your success is a key to not just surviving, but thriving.

Increasingly, it will come down to your local talent – those who entertain, inform, foster relationships, and act as brand ambassadors. They are gold, and if it’s your job to retain them and keep them engaged, understand the playing field.

At a time when so many in the industry are cavalierly letting them go, it’s an opportunity for a company, a cluster, or a station to create that welcoming presence that will keep great talent happy and excited about their jobs.

After the July 4th holiday, we will be launching AQ3 – our third research survey among air talent in commercial radio in the U.S. This year’s questionnaire will be very different, thanks in no small part to COVID. How has the radio environment changed? What does talent need to know about their peers. And what can management and ownership learn about the current mindset of air personalities? The study is in collaboration with Morning Show Boot Camp, where it will be debuted.

be very different, thanks in no small part to COVID. How has the radio environment changed? What does talent need to know about their peers. And what can management and ownership learn about the current mindset of air personalities? The study is in collaboration with Morning Show Boot Camp, where it will be debuted.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

God, where was this and Mike’s article before I got let go in October?! So you’re NOT supposed to let your ratings successful, legacy, innovative morning show go in the middle of a pandemic with a special needs kid and then hire someone to replace them only to have them walk a month later because they were a cancerous person in the first place and then replace again but this time with the husband of the Operations Manager?

Noted.

PS…Yes, I’m still bitter about it.

Jerry, I get that. My belief is that many broadcasters have had a hard time getting their heads around the notion they’re competing with trillion dollar tech companies, in addition to radio stations up and down the dial. Sadly, budget cutting became a solution to a host of problems, even though it has often made the quality of local radio worse.

Great piece Fred, and I’ll add one note to theory of change. Much of the time it’s about cost, not about performance, and that’s the biggest mistake of all. Evaluation is an all encompassing process and the financials are just a piece.

What exactly defines a “star talent?” Seems very subjective.

Gary, it is somewhat subjective. Ratings matter, and ideally, the “star” outperforms the station. But that can be deceiving, depending on the daypart and the format. I look at ratings performance, along with research. Quantitative data provides familiarity and preference (likeability) so you can see how talent stacks up next others at the station and also the market. Focus groups can come in handy, too. Are listeners aware of the talent without prompting? How do they talk about him/her? You can see/hear the passion. Other factors include successfully working social media & other channels.

But when all is said and done, you’re right – it is somewhat subjective. I’ve watched and listened to audiences talk about Howard Stern and other syndicated stars, as well as local talent in al dayparts. It’s collective impressions to be sure. I’d sum it up like that Supreme Court ruling on pornography: hard to define but you know it when you see it.

On some level, this situation is almost silly. Listeners prioritize talent over everything every other reason for listening to radio, ownership has research that confirms it, yet they give local management very few tools to keep them happy or provide an environment that fosters creativity.

For that reason, this is a rare case where I don’t agree fully with Fred’s bullet points. Here are mine:

1) Forget making them a member of a team – there is no team anymore, unless you count the people 1000 miles away. This is about a personal, one on one relationship between management and talent and that’s hard to cultivate, as increasingly, management and talent are in different cities. The onus is on management to make it their job to be in the talent’s city enough to build that relationship. When you have no real authority over anything, personal relationships become most of your job and almost all of your leverage for retaining talent – on air or otherwise.

2) The company has already thrown themselves under the bus, so there’s no real need to worry about that. I’m not suggesting playing good cop/bad cop with the company, but most people, star talent included, understand how their company is run, who makes the decisions, what drives them and their relative importance to all of that. By all means, look for ways to support your company, but telling lies to defend it only weakens the one asset you have in retaining talent. If the company does something that talented person doesn’t like, try to counter it by doing something they do. When I was in the national rep business, “It’s business as usual” was the rallying cry from mid level managers after our company lost a station client to another, but hadn’t signed the papers yet. We all knew that wasn’t even remotely true and what that manager was effectively saying was, “…I will lie to you about obvious things with reckless abandon and you can’t believe anything I say”. I advise against painting ones self into that corner with a company defense, instead, keep it personal while both of you accept what is widely know about your company.

3) Understand the unique personality that usually accompanies great talent. A consultant once suggested to me that the creative spike that top talent has (compared with most people) is often balanced by a dip somewhere else. Look for that dip, recognize and manage it. Understanding someone and supporting a star’s weaknesses by having their back when they show themselves will go a long way toward forging a relationship that could keep a fine talent.

Things in radio already had gotten more than too impersonal before the pandemic, then we all had to hide our faces and keep our distance. IMO, the best way to keep top talent is do the opposite.

I love it when we argue, Bob. 🙂

Seriously, you raise some key points, especially #3. It’s a great observation that speaks to the psychology of personnel management.

Your first two points are understandably cynical. And I expect you’re not alone in seeing the situation through that jaundiced lens. I acknowledge that it has become this way at several companies, mostly to their detriment. But I really wrote this post for the companies that still believe and are very much in the personality game. They exist, I work for a number of them, and I can tell you they are good actors.

I would never ask a program director to lie – especially if they’re just covering up for wrong-headed management dictates. To find an accommodation or compromise with the powers that be allows you to be (mostly) truthful with your staff. That’s different than trashing them to talent. And if the situation is untenable, my advice (easy for me to say, I know) might be to ask yourself whether you really want to work for these guys.

Middle management is a series of compromises – rarely do you totally get your way. But there’s a way to let talent know that even though you disagreed originally with the current course of action, you support the enterprise and will do what you can to accomplish the goals. Or again, look elsewhere.