It is fascinating to look at innovation during the pandemic. Some major brands have suffered of course – Neiman Marcus, GNC, Gold’s Gym, California Pizza Kitchen – and the list goes on.

Last week, National Restaurant News revealed a minimum of 100,000 restaurants in the U.S. have closed since the start of COVID. And to make matters more dire, the latest survey from the National Restaurant Association reports four in ten restauranteurs say it’s unlikely they’ll still be operating six months from now.

And yet, many business endure. They’ve figured out a way to not only survive – but to thrive – amidst the chaos that is the coronavirus.

Clearly, innovative solutions to existential problems will separate the brands that will come out of the pandemic stronger than when this all started. But according to Reed Hastings, CEO of Netflix, it will take more than that.

He’s got a new book – No Rules Rules – and it’s on my list. Now, as you know, scores of marketing books come out each week. I’ve got a book shelf lined with them. But this one I will buy.

I was fortunate enough to see Hastings keynote at CES a few years back. While the presentation was little more than a stump speech setting up Netflix’s growth outside the U.S., it was a clear picture inside the mind of a CEO whose company was mailing out DVDs in red envelopes just a few years ago.

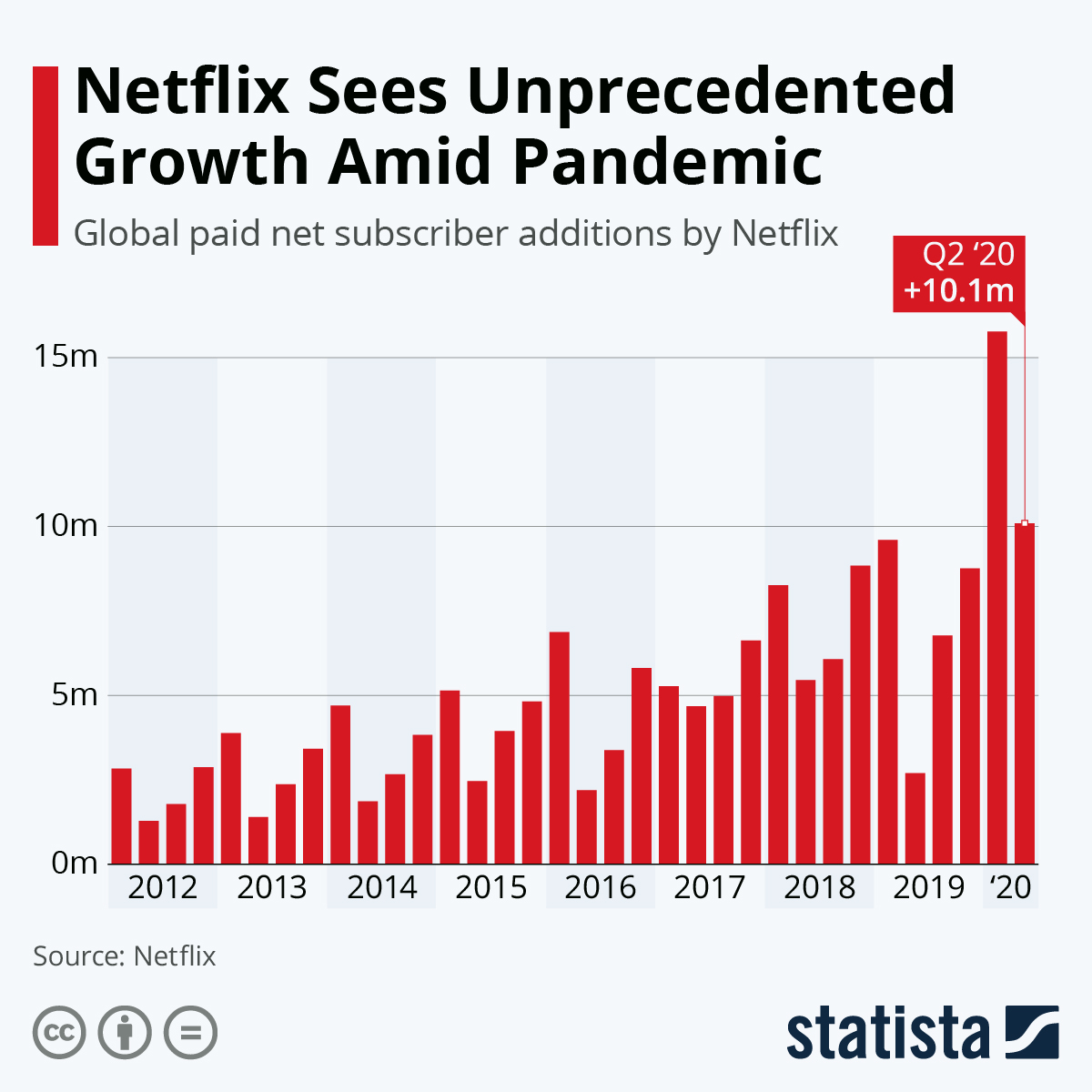

While virtually every video streaming platform worth its salt will show growth this year – some of it meteoric – there’s Netflix and then there’s everyone else.

How have they managed to pull it off, and what’s the story behind their amazing growth curve in 2020, a year that continues to test all of us in business in profound ways?

While some brands insist on outside voices – yes, consultants and the like – Hastings has turned it inward. His motto is a simple one, but he uses ALL CAPS to make sure everyone’s listening:

DON’T SEEK TO PLEASE YOUR BOSS. SEEK TO DO WHAT IS BEST FOR THE COMPANY.

There’ s nothing necessarily profound or original there. In fact, chances are you’ve heard a boss, owner, or CEO actually say it.

But not mean it.

Inside Netflix, the culture is called “farming for dissent.”

It’s about “socializing” ideas by seeking out different ideas and perspectives from all corners of the company. And in the book, Hastings relates the debacle that was Quikster. Back in 2011, Netflix offered a combined service of mailing DVDs and video streaming.

It’s about “socializing” ideas by seeking out different ideas and perspectives from all corners of the company. And in the book, Hastings relates the debacle that was Quikster. Back in 2011, Netflix offered a combined service of mailing DVDs and video streaming.

At the time, Hastings knew streaming was the future, but many people were still renting DVDs. So they created two video companies – the Netflix we know it as today, and Quikster, the company that would still be mired in red envelopes.

Customers weren’t just pissed off – they revolted – angry over having to manage two video subscriptions from the same company rather than a single solution. And as the stock price cratered, Hastings even went to YouTube to apologize for the strategic error.

But as frequently is the case, adversity led to a reawakening. And later when he reconnected with his army of upper managers, some said they knew the Quikster move wouldn’t work – or that it was crazy. But they were afraid to step up and disagree with the boss.

So Hastings did a 180 – and today, he calls not stepping up with differing opinions a dereliction of duty: “By withholding your opinion, you are implicitly choosing to not help the company.”

Now, within Netflix – top to bottom – there’s a system and a protocol in place for stepping forward – but also inviting teammates to offer their comments, both supportive and dissenting.

Now, within Netflix – top to bottom – there’s a system and a protocol in place for stepping forward – but also inviting teammates to offer their comments, both supportive and dissenting.

Employees can use scaling systems (accompanied by comments). And then for the tough calls, upper management use the spreadsheet of opinions – pro and con – to better form their thoughts.

That process led to the creation of a kids division for Netflix – something Hastings originally didn’t believe in. To his way of thinking, it was adults in the household that drove his brand.

But by socializing the idea – and many Netflix colleagues pointed to “the next generation of Netflix customers” as a key reason why this direction will work – Hastings socialized the idea at a company gathering that brought together 400 of his best people. And each participant received a small card that asked this question:

“Should we spend more money, less money, or no money on kids’ content?”

And then working in small groups, his teams went to work to suss out the idea. As Hastings concludes, the concept received “a tsunami of support.” And it led to hiring a new VP of kids/family programming from DreamWorks, and soon Netflix was producing its own animated programming.

The company has now won multiple awards for its kids shows, but more importantly, it’s built a runway to the future. As Hastings humbly admits, “If I hadn’t taken the time to socialize the idea, none of this could have happened.”

I’ve made the same mistakes myself at Jacobs Media and jacapps over the years. Oftentimes, I get so intensely married to an idea (usually my own) that it can be difficult for others to step in and ask those all important “What if?” questions. And of course, the other side is the ideas I’ve killed or that never got off the floor because – IMO – they weren’t worthy.

The concept of “farming for dissent” among a company’s workforce means putting their most invested people to work. Employees on the payroll may not always be intensely loyal, but they have skin in the game.

And it can be effective in all organizations – even the Supreme Court. We are remembering Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg this week – the Notorious R.B.G.

And it can be effective in all organizations – even the Supreme Court. We are remembering Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg this week – the Notorious R.B.G.

One of the ways she earned that nickname was with her dissents – the decisions the court made where she spoke on behalf of the minority opinion, the unpopular stance, and maybe even the ones that didn’t make “the boss” happy.

In this year where convention has been turned upside-down, we’d all do well to get out the plows and back-hoes, look at our organizations and do some “farming for dissent.”

For the sake of our companies, we could all stand to be a bit more notorious.

- Can Radio Win “The Last Touch/First Touch Challenge?” - April 4, 2025

- How Will Radio Fare In The Battle For The Fourth Screen? - April 3, 2025

- Like A Pair Of Old Jeans - April 2, 2025

Before the dictate:

Never miss the opportunity to drop the “T” from Task.

Good one.

Listening to those who will speak truth to power is rare among most radio execs. Surrounding yourself with people who are good at the things you are weak in is the first step. Such a simple concept which always works for the betterment of the company.