If you’ve worked in radio for a minute or two, you’ve undoubtedly been through a format change. Chances are, more than a few of them.

And if you’re an owner, manager, or programmer, you were likely responsible for its outcome. To pull off a successful change of formats, lots of details – beyond how the new format sounds out of the gate – need attention.

There’s the secrecy element – the awareness of who needs to know, who is trusted, and who is better off being surprised.

And then there are all those moves that need to be orchestrated. Notifying Nielsen, updating the website and the app, and presenting the big move to the audience – those who may be elated by the new format and those bound to be indignant about the change. Both groups will probably end up on social media, pleading their respective cases about the wisdom or idiocy of the switch.

But then there’s the sales part of the equation – perhaps the variable that’s most precarious. Smart ownership is cognizant the ratings will most likely swing – wildly – as the old audience may be unhappy with the change while hopefully, new listeners will come in droves to replace them. Its to be expected.

But the revenue side is almost always a tricky play because advertising generated by the previous format is booked, scheduled, and ready to air. The challenge is keeping these clients intrigued enough by the new format to want to still run their spots.

When the switch is a small leap, say from AC to Hot AC, it is often possible to hold onto the business. When it’s a more radical shift, however – perhaps from Classical to Alternative, it’s a tough pitch. I was involved with the latter once, and the salespeople don’t even try to hold onto booked billings. Aside from being shell-shocked themselves, everyone agrees it’s a bridge too far.

But when a new owner takes over existing station, it’s usually not much of an issue to advertisers at all. That is, unless the new regime opts to clean house, make a lot of noise, and draw unnecessary attention to itself. In the advertising game, it is rarely a good thing when a brand becomes unstable.

of noise, and draw unnecessary attention to itself. In the advertising game, it is rarely a good thing when a brand becomes unstable.

That’s when the bottom can fall out of the sales situation. And that’s what we’re looking at in this post – the best and worst practices involved in the facilitation of change. In these cases, we are taught to emulate the proven path to success. But we’re not always told what not to do. In the case of Twitter, these last few months, it’s been mostly a case of the latter.

A story in Forbes by the always insightful Brad Adgate reveals what many of us have already assumed – advertisers bailed not long after Elon Musk took over Twitter thanks to the bombast and vitriol the new owner himself caused.

In fact, the numbers indicate Twitter sales cratered by nearly 50% last November – just weeks after the owner of Tesla walked into the social networks headquarters carrying a sink. Adgate tells us the sales quivering at Twitter was also accompanied by steep competition from other social media platforms, along with the economic headwinds buffeting all advertising sales efforts.

In fact, the numbers indicate Twitter sales cratered by nearly 50% last November – just weeks after the owner of Tesla walked into the social networks headquarters carrying a sink. Adgate tells us the sales quivering at Twitter was also accompanied by steep competition from other social media platforms, along with the economic headwinds buffeting all advertising sales efforts.

But it was Musk’s ham-handedness that helped doom Twitter’s revenue generation in November. It wasn’t just about new advertisers taking a wait-and-see approach about how the new Twitter would go over with users. Thanks to Musk telegraphing his controversial moves, many agencies and the accounts themselves sensed trouble at Twitter.

Standard Media Index, the folks who publish ad spending reports, found that many marketers simply pulled “pre-booked” campaigns leading into the holiday season. In fact, it appears the Musk hangover will reverberate in this month and in February where ad sales are down from previous years.

Advertisers had a lot to be concerned about Twitter when Musk moved into the corner office: mass layoffs, policy changes, brand safety, and general instability. As you may remember, Twitter was a top item in the news cycle during those weeks, focused on staffing issues, new edicts, policy shifts, and lot of noise.

Twitter itself was trending, but that’s not necessarily what agencies want for their clients. Whether in radio or social media, marketers want their advertising to appear on respected brands that aren’t overtly embarrassing, inconsistent, political, or controversial (unless that’s what defines the product).

Over the years, Adgate points out Twitter has been plagued by consistently being overshadowed by bigger reach social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and many others. From its beginnings, Twitter was not for everybody. On the one hand, it was a social platform that broke news. Its following of celebrities, sports stars, and journalists set it apart from the other social brands.

many others. From its beginnings, Twitter was not for everybody. On the one hand, it was a social platform that broke news. Its following of celebrities, sports stars, and journalists set it apart from the other social brands.

Yet, despite being in business for nearly 17 years, Twitter’s “cume” – its number of total users – pales in comparison to its competitors. Adgate points to a a Forrester report showing less than 2% of all digital ad dollars went into Twitter’s coffers last year.

And Twitter’s reach is only about one-third of Facebook’s, and about half of Instagram’s. Forrester also reports Twitter’s “unaided awareness” is scary low. Get this: half of U.S. adults who are online have never heard of Twitter after all these years.

Our Techsurveys show pretty much the same horse race. While newer entrants like Snapchat and TikTok have dominated social conversations these past several years, Twitter has always been something of a niche product.

This data makes you wonder why Musk would pay $43 billion for Twitter in the first place. Its low billing and mediocre reach aren’t the kind of numbers most investors would find promising, reassuring, or convincing.

But maybe Musk’s strategy is to simply generate buzz and hope that somehow converts to “cume.” By making Twitter more top-of-mind, logic suggests more prospective users would join the platform to see what all the talk is about. Since announcing his intention to buy Twitter last spring, and then having to actually go through with it this fall, Musk has definitely been successful in keeping his new social network in the news, as well as a source of humor (or ridicule) on late night TV talk shows.

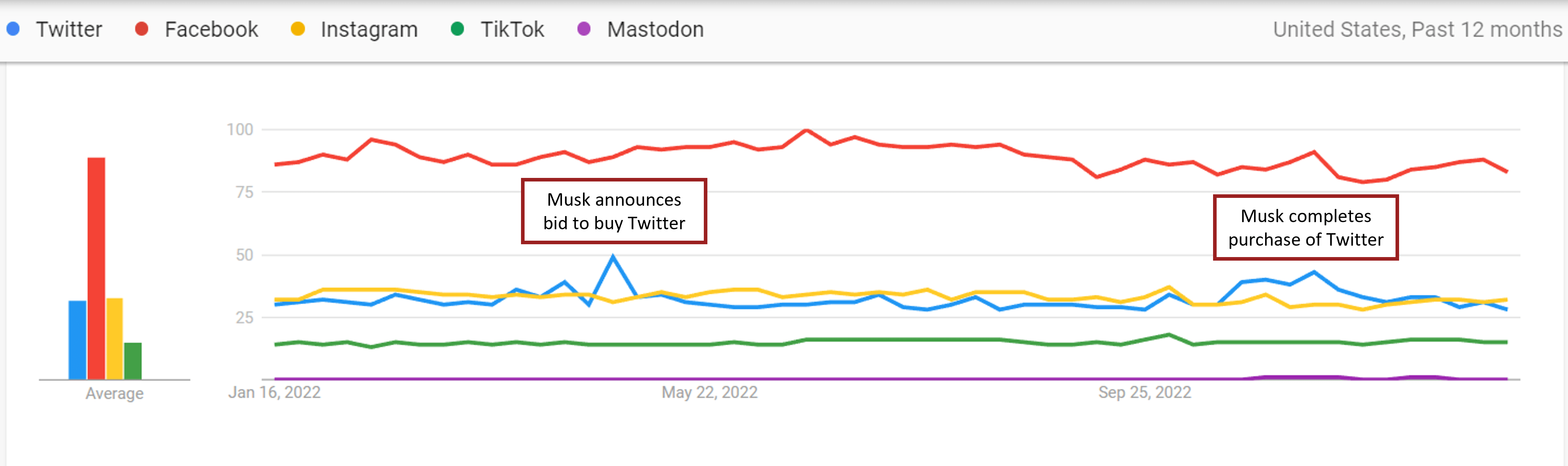

Twitter itself has been trending. But as that actually translated into consumer interest? To make that determination, Google Trends can be a great source. By plugging in search terms, you get an idea of how a topic is trending. After all, if people are looking for more info on a brand, they’re likely to search for it. Here’s how American adults searched for some of the key social platforms, plus Mastodon – the channel that has tried to attract Twitter ex-pats. Keep an eye on the blue line – Twitter:

On the chart, you can see the peaks from this past year, consistent with the news that Musk first announced he wanted to buy Twitter, and then the October surprise when he actually had to consummate the deal. By this January, however, search levels had normalized – back in the pack with Instagram, and well below Facebook.

There’s an art to saving the business, whether you’re taking over Twitter or flipping your format to Variety Hits. In fact, there are “best practices,” whether you’re flipping format or buying an existing social media platform. Even though change is in the air, the smart money is on enticing advertisers to hang with you.

But then there are the things not to do – “worst practices” – that get organizations in trouble, especially when they believe the business they’re buying is an easy one.  Taking over an existing enterprise, even historically unsuccessful ones like Twitter, is a balancing act requiring much nuance and precision. Ultimately, all media brands – traditional, digital, or social – have to play the game and focus on giving advertisers what they want.

Taking over an existing enterprise, even historically unsuccessful ones like Twitter, is a balancing act requiring much nuance and precision. Ultimately, all media brands – traditional, digital, or social – have to play the game and focus on giving advertisers what they want.

When you’re the richest man in the world, anything’s possible. Musk’s unconventional methods might actually pay off in the long run. Perhaps he can cheerlead this brand to a better position than it’s occupied over the past decade or so.

Or maybe not.

Whatever the case, his a cautionary tale of what not to do when you’re taking over a new acquisition.

And that brings to mind some poetic license for a well-worn piece of advice:

“Don’t count your Twitter birds before they hatch.”

- The Exponential Value of Nurturing Radio Superfans - April 28, 2025

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

Fred, this story strikes me as a cautionary tale about the Peter Principle, CEO Edition. In essence, in his acquisitive career Mr Musk appears to have risen to the level (ie, number of companies) where his shortcomings have become obvious, and restrictive. That is, unenlightened by his cowering friends/associates/sycophants, his hubris and caprice led him to attempt a bridge too far; and now he is stuck with a failing enterprise whose complexity he vastly underestimated, and his every move worsens the situation. And this has distracted him from running the earlier companies where he demonstrated competence–as reflected in Tesla’s concurrent drop in market value, for example.

Bringing this back to radio, it’s hard to miss at least one obvious lesson: When you have risen to the level of General Manager, or you have simply bought a station, consider what value you saw in your investment of time and/or money and hit the pause button before you make major changes, because until you’re actually in the driver’s seat you don’t really know how this vehicle handles.

John, I’m sure the late Laurence Peter would be happy that he still has relevance, some 33 years after his passing (the anniversary was last Thursday, in fact) and well over a half-century since he introduced his “Peter Principle” in the book of the same name.

Given our business, I’m sure we’ve all had our share of people who rose to their own level of incompetence, as Dr. Peter said. Mine was in 1984, when I was brought back to a station I had programmed as an A/C five years earlier in my hometown market, as it transitioned from AOR to CHR under its second owner since my original time there. Our GM, despite being told by corporate that they wanted something closer to what I had done before (yes, I was hired by corporate, not by the GM), decided that an underpowered Class A could take on the dominant CHR, with the second-best FM signal in the market.

No outside promotion. No billboards, no newspaper ads, no involvement in the community. The first book came out and the numbers were lower than the last book as an AOR. Despite the GM’s philosophy, I started transitioning the station to what corporate wanted. When the GM noticed that, he brought in his own consultant, at which point I tendered my resignation both to him and to corporate.

It all happened in the space of five months. He and his consultant lasted about another three months, and then both were summarily dismissed and the station went to a live-assist soft A/C, using a format from a syndicator corporate had recently acquired. They sold it off less than two years later, because the station never recovered from the fiasco of the General Incompetent Manager.

I still find myself wondering how he managed to convince corporate to keep him on, given that they were constantly caught in the middle of arguments between him and me.

Musk, however, has risen to a whole new level of the Peter Principle. We may have to resurrect Dr. Peter to write a sequel.

The parallel between my story and what Musk is doing is that both are examples of what you said in your second paragraph, John. My GM never really understood what they had the responsibility for (neither does Musk now) and trying to make their “new toy” into what their own personal desires and tastes were completely ignored what the marketplace wanted.

(BTW, my old station changed hands two more times and has had a Regional Mexican format for most of the past 25 years.)

K.M., I’m sure many people can relate to your radio application of Dr. Peter’s famous principle. Typically, those who are promoted to a job for which they incompetent end up flaming out – OR in a few cases – grow up quickly, understand the mess they’re in, and meet the moment. But that’s a rarity.

The problem with Musk is 1) who’s going to tell him? and 2) he will never need the job (and the money) so badly that he’s willing to change. Maybe best case scenario is that he’s willing to step aside, hire a real CEO, and let her do here job. I’m not holding my breath.

I think you’ve nailed the essence of he problem, John. For those who don’t remember the Peter Principle, it was a “thing” in the world of business back in the 70’s. It essence, it stated that many people rise through the ranks, eventually reaching a job for which they’re not competent. It became a convenient shorthand for employees experiencing problems with bosses that had shaky credentials, talents or both.