When we think about the revolutionary moves Netflix has made over the years, most think about the transition from mailing DVD movies in red envelopes to the video streaming they’ve made famous today. And there’s a lot to be said for that. Those advancements destroyed Blockbuster and vaulted Netflix to the top of the heap in a new category – unlimited video streaming that’s commercial free. It also enabled us to scroll through content while sitting on the couch, having it appear seconds later on our TVs.

But perhaps Netflix’s biggest innovation was the idea of a subscription model for their service – an all-you-can-eat package – that allows us unlimited consumption of their movies, TV shows, documentaries, and other video content on the platform.

To a great degree, Netflix spawned the “subscriber economy,” now a vast array of goods and services for which we pay a monthly fee. And so many others have followed suit, creating the concept where we no longer own much of the content we consume – movies, music, games – we subscribe to services that simply allow us to use them.

And that’s why so many have popped up in just the past few years: Hulu, Paramoumt+, HBO Max, Peacock, and myriad others are hoping to capture just a few bucks every month, because chances are, we’ll blindly renew them or better yet, forget we subscribe in the first place.

And for most of us, one video streaming service is not enough. A sneak peak at Techsurvey 2022 (coming in April) reveals nearly nine in ten core radio listeners subscribe to at least one video streaming platform. Even more impressive, three-fourths pay for two or more of these services.

There are now so many subscription services that apps have been developed to help us track them, and if desirable, cancel the ones we aren’t using enough to justify paying for them. Truebill is just one of them, allowing us to track our spending, reminding us when our subscriptions are coming up for renewal, and helping us cancel if desired.

If you ask the average person how many subscription services they now pay for the privilege of using, they can only venture a guess. The better question is how much they’re actually spending each month, and they cannot tell you with any exactness.

The subscription consulting firm, West Monroe, actually tracks these metrics. They conducted the newest edition of “The State of Subscription Services Spending” last summer among 2,500 American consumers.

2,500 American consumers.

The main takeaway? We have increased our monthly spend on subscriptions from 2018, we’re less aware of how much we’re spending, and more of us have tried new services as the economy becomes more digitized.

This “Netflixification” of our lives is in full swing. It’s a term – although more of a condition – I first read about in Wired. Whether we pay for the ability to shop at Costco, Sam’s Club, online at Amazon Prime, or subscribe to multiple audio and video content services, the ways in which our lives roll has changed.

And the companies whose services we subscribe to – or better put, rent from – hope we lose track of these $5, $10, and higher fees and simply let them seamlessly extract their charges from our credit cards.

In a story titled “Apple Wants You To Subscribe to the iPhone” by Boone Ashworth, we learn how Apple may be developing a service where we can rent their $1,000+ smartphones (and maybe iPads) for a subscription fee rather than actually paying for the device. As Ashworth notes, this move furthers the company’s mission “to merge every device and service into a unified Apple ecosystem.”

In a story titled “Apple Wants You To Subscribe to the iPhone” by Boone Ashworth, we learn how Apple may be developing a service where we can rent their $1,000+ smartphones (and maybe iPads) for a subscription fee rather than actually paying for the device. As Ashworth notes, this move furthers the company’s mission “to merge every device and service into a unified Apple ecosystem.”

And they’re not alone. Ashworth tells us Peloton is considering something similar with its costly exercise bikes. In this way, you don’t have to repair these expensive devices when they break down. And a subscription allows you to have the latest model, rather than hanging onto that old device for years and years.

Here’s the interesting part. Companies you would not expect are launching subscription programs. A blog post in Vindicia by Jesus Luzardo says fast food restaurants are entering the fray.

Taco Bell’s plan may be brilliant. For a $10 monthly fee, you can eat a taco a day. Luzardo says a logical tie-in with food delivery apps like DoorDash could provide no delivery fees if you’re a  subscriber.

subscriber.

But here’s the best. Research among Taco Bell subscribers revealed one in five subscribers were new to loyalty programs. Luzardo concludes these monthly programs “are an excellent way to acquire customers and keep them continually connected to a brand.”

After all, aside from the money, isn’t that a goal of virtually every brand with a consumer interface – build loyalty and engagement with customers.

You might be wondering when people will burn out on all these monthly payments for goods and services. The folks at MIDiA are measuring what they call “peak subscription” – the point at which consumers start cutting these conveniences out of their lives. As more and more brands launch these pay-by-the-month programs, the thinking is that we’ll reach that point sooner rather than later.

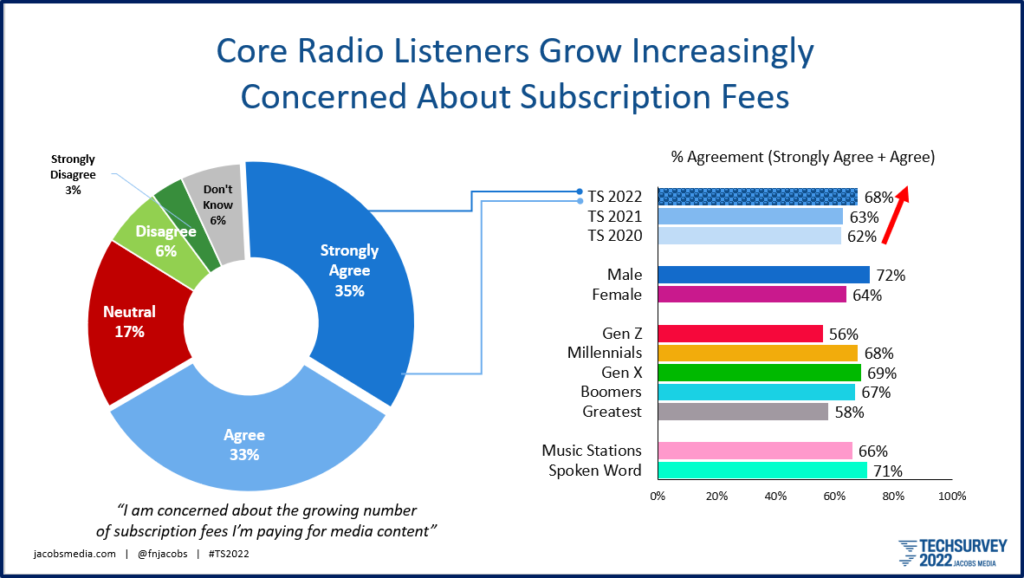

Another insight in Techsurvey 2022 shows concern about these mounting expenses is increasing. In fact, two-thirds now agree with statement, “I am concerned about the growing number of subscription fees I’m paying for media content,” up from the year before.

But even during a period of high inflation, ignited by post-pandemic spending and the Ukraine war, us consumers don’t seem in the mood to toss our subscriptions overboard.

MIDiA analyst Tatiana Cirisano makes an important point about the chances we’ll see peak subscription anytime soon:

“Today’s subscription-everything mindset is just one part of an entertainment industry where it increasingly feels like our every move is monetized. As attention saturation meets subscription saturation, the cost of digital living continues to rise.”

And that raises the question why radio has been a bystander during this period. Let’s put a pin in commercial radio, and come back to it. It has a different business model, highly dependent on commercials.

Public and Christian music radio, on the other hand, generate by far the best Net Promoter Scores – that’s word of mouth – in radio broadcasting, well above the levels of the average country, rock, hip-hop, or talk station. And each is highly dependent on listener contributions – “membership” in public radio and “donations” in Christian – to sustain their operations.

Public and Christian music radio, on the other hand, generate by far the best Net Promoter Scores – that’s word of mouth – in radio broadcasting, well above the levels of the average country, rock, hip-hop, or talk station. And each is highly dependent on listener contributions – “membership” in public radio and “donations” in Christian – to sustain their operations.

Each of these platforms inflames their core audiences every time they hold a “pledge drive” (or “shareathon” as they’re often called in Christian radio). Every time one of these multi-day fundraisers takes place, the ratings (especially in PPM markets) suffer greatly, while stations often turn off many of their biggest and most rabid fans. To a person, they understand why stations have to interrupt their content to raise the necessary funds to stay on the air, but most of them despise pledge.

ratings (especially in PPM markets) suffer greatly, while stations often turn off many of their biggest and most rabid fans. To a person, they understand why stations have to interrupt their content to raise the necessary funds to stay on the air, but most of them despise pledge.

The ironic part is that public radio, in particular, is amazing. In so many ways, its stations and networks have not only adapted – they’ve innovated. When it comes to podcasts, apps, newsletters, and other technological forays, the platform has done many novel things.

But when it comes to fundraising, it’s like dial phones, mood rings, pet rocks, and tote bags – artifacts from the past that while quaint, have no relevance to today. The concept of pledge drives is like being stuck in the Dark Ages.

Nowadays, creatives raise money with Go Fund Me campaigns, and similar platforms such as Kickstarter, Bonfire, and IndiGoGo. Or they use a platform like Patreon or Buy Me A Coffee.

Given all the creativity public radio exhibits in so many ways, you’d think someone would have come along with an antidote to pledge drives. And often, public radio veterans will swear these anachronistic fundraisers still work, even though they are terribly dated, while causing all sorts of collateral damage to brands. Plus, few have ventured out to try alternative methods of revenue generation.

to pledge drives. And often, public radio veterans will swear these anachronistic fundraisers still work, even though they are terribly dated, while causing all sorts of collateral damage to brands. Plus, few have ventured out to try alternative methods of revenue generation.

If young listeners are the goal – and public radio managers will readily acknowledge they are – how do you explain to a twentysomething what being a “member” of a public radio station actually entails? When they hear the call to “donate,” will they think of public radio as a church passing the plate or a charity hoping to tap into our better angels?

I ask these questions not because I’m convinced Gen Z’s can be easily turned into “subscribers,” but because Netflix, Amazon Prime, and SiriusXM at least use language that is clear and up-to-date. Consumers realize that if they pay their $20/month subscription fee to Netflix, they can watch or binge “Squid Game,” “Bridgerton,” and everything else in the library as often as they like. Cancel the service, and that steady stream of video content is shut off. That’s the deal.

In public radio, the content never ends. Whether you heed the call to “become a sustaining member” or you’re an annual giver, programming will continue on the radio, via the stream, and even podcasts. For the system to work, public radio fans must feel an obligation to donate based on how they value the programming and because of how much of it they consume. If that doesn’t work, public radio pledge drives will first try guilt, and then resort to threats – if you don’t support these costly programs, they will surely go away.

In public radio, the content never ends. Whether you heed the call to “become a sustaining member” or you’re an annual giver, programming will continue on the radio, via the stream, and even podcasts. For the system to work, public radio fans must feel an obligation to donate based on how they value the programming and because of how much of it they consume. If that doesn’t work, public radio pledge drives will first try guilt, and then resort to threats – if you don’t support these costly programs, they will surely go away.

But they rarely, if ever, do. Go down to the left end of the FM dial, and see for yourself. All systems are go. You can listen whether you’re a member or you’re not.

In fact, the dirty little secret in public radio is that about the same percentage of listeners actually pay for this privilege as did in the 1970’s. That’s right – somewhere in the neighborhood of 10-15% of cumers actually step up and write a check or swipe their credit cards. And yet, nearly nine in ten of them are willingly sending money to Amazon, Netflix, and other subscriber-based networks and content verticals.

And based on what we’ve seen during the COVID years, that trend will continue unabated until it no longer works. No one knows if and/or when consumers will get so fed up they start dumping their content subscription services like they have cut the cord with cable and pay TV.

You should know NPR has recently launched a “subscription membership” (yes, it’s called “Plus”) allowing those who pay to listen to their podcasts without sponsor messages. That is, commercial-free. We “tested” the concept in last year’s Public Radio Techsurvey last summer. Notably, an impressive three of every ten (30%) weekly podcast listeners say they’d be very or somewhat likely to try this platform. The most enthusiasm – not surprisingly – is voiced by Millennials.

When it comes to shaking up the fundraising model, public radio has to do better. Their programming quality is that good, deserving more support from those who regularly listen. Many of those who do not support the programming content they enjoy will cry poor, but I promise you most of them have found a way to afford Disney+, Spotify, and SiriusXM.

When it comes to shaking up the fundraising model, public radio has to do better. Their programming quality is that good, deserving more support from those who regularly listen. Many of those who do not support the programming content they enjoy will cry poor, but I promise you most of them have found a way to afford Disney+, Spotify, and SiriusXM.

And then there’s Christian radio which elicits the very best Net Promoter Scores of all the radio we test. Fans sing the praises of these stations, exhibiting unprecedented loyalty. Many of these stations may fly under the radar, but they’ve developed a hardcore fan base that swears by their inspirational programming. But in the donations department, it could frankly be a lot better.

If you think I’m going to let commercial radio off the hook, you’ve got another thing coming. Sadly, it is hard to imagine large numbers of people sending their hard-earned money to their favorite hip-hop, sports, and alternative station. The incessantly long commercial breaks – two gargantuan clusters of revenue an hour – signal that these stations are greedy enough as it is. Why on earth would anyone send them even more money?

So, it is inherently a much tougher putt. But could some of the best commercial brands cook up subscription packages of value to their core fans? Programs might involve access to concerts – special seating areas, meet & greets, drinks and food discounts, and even special parking and members only access. You might include seeing certain shows with a station personality or celebrity guest. Subscriptions could be creative collaborations between the station and key venues, restaurants, bars, and other outlets. They would require extensive planning and sterling execution. Only top-of-the-line stations could pull this type of program off, but they’re out there.

The bottom line is that consumer wallets seem deep when it comes to entertainment, information, and access – attributes that some radio stations have right now. Tapping into that money pool is what’s motivating brands across the spectrum.

The bottom line is that consumer wallets seem deep when it comes to entertainment, information, and access – attributes that some radio stations have right now. Tapping into that money pool is what’s motivating brands across the spectrum.

There are two other takeaways from that West Monroe subscription spending study that jumped out at me:

- Music streaming services are especially likely to generate user satisfaction. In fact, one-fifth of these consumers (21%) describe themselves as “happily hooked” (tied with Amazon Prime, and behind only book services).

- Now is the time leverage subscription revenue. The study’s authors say these services are becoming more engrained in everyday life.

So radio – why not?

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Satellite Radio deserves some credit here. Both Sirius and XM had a subscription based model going when Netflix was still just mailing DVD’s. And it was for *radio*.

Indeed they do, Jeff. Up to that point, I think I had just subscribed to Newsweek, Rolling Stone, and Mad. Thanks for the comment.

If Jeff hadn’t said it, I was gonna. Sirius and XM were the trailblazers. They developed the archetypal conditional-access devices necessary to control their revenue and terrestrial radio blew the opportunity to do the same using IBOC technology. I read about in the trade press in the ’90s, Fred. But radio flinched and rested on its laurels, which are now dessicated.

Your suggestions point to some possible strategies for rescue. I hope someone runs with them.

Me too, John. There’s a lot of money out there, and a model that’s working well with other media verticals. It will require investment – research, people, marketing – all variables that make the difference in whether initiatives usually succeed. Thanks for taking the time to comment.

I think radio needs to become lots more locally oriented. Music streaming services are popular but it’s hip background Muzak and not radio which can become an active companion. Live music can also be broadcast far more inexpensively than ever.

Bob, the local piece continues to be an available brand attribute for most radio stations. Sadly, many believe it’s not a differentiator. Thanks for the comment.

You still need content to sell. Radio’s mantra has been to ‘do the same with less,’ and that won’t cut it to separate customers from their cash. Much like the success of Netflix, and others, has come from creating new content and not relying exclusively on what they can source from others.

What seemed strange and archaic to us for many years now resembles today’s subscription model.

Apparently the BBC was ahead of its time… 🙂

The BBC’s income is around £5 billion (£4.943 billion in 2020, to be precise).

Of this, around £3.5 billion is generated from the licence fee. But a significant amount is generated through other, non-public means.

Fred, Thanks for sharing info about something that keeps public radio managers awake at night.

And I understand why, Regina. I have to believe it is a solvable problem if there’s a will to solve it. Thanks for commenting.