Last week, we took a look at Netflix’s recent weak first quarter numbers, as well as projections showing a slowdown during 2021. You’d think that given the COVID disruptions with millions of Americans still staying close to home, streaming video platforms would still be killing it.

Except for one annoying problem:

Netflix is running out of hit shows.

In their most recent financial statement to company shareholders, the corporate team at Netflix went right to the heart of the issue:

“We believe paid membership growth slowed due to… a lighter content slate in the first half of this year, due to Covid-19 production delays.”

In other words, a dearth of hit shows – TV series, blockbuster movies, and compelling documentaries.

To that end, Music Business Worldwide’s Murray Stassen made this point in a story last week:

Interestingly, streaming audio services have had a better run during this same period. Stassen says that according to the RIAA, subscriptions to services like Spotify and Amazon Music in the U.S. increased by more that 15 million in 2020.

And revenue followed, up by more than 9% to north of $12 billion last year.

Not too shabby as they say – until you look under the hood.

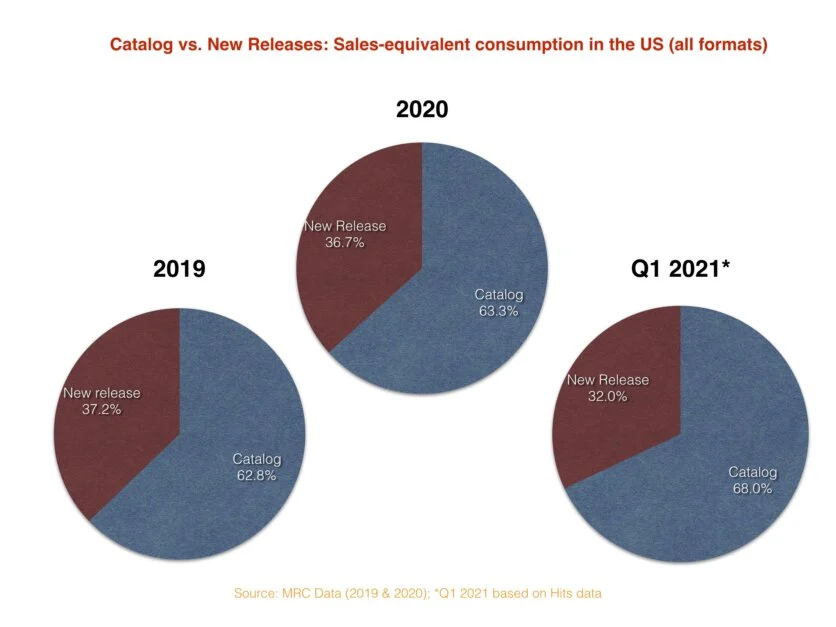

The lion’s share of the U.S. music market is catalog product. Hits Daily Double says “gold” now accounts for two-thirds of the market – and it’s projected to run even higher in Q1 of this year.

Classic Rock?

That genre accounts for only a portion of it. Much of it is newer music from the streaming era. Still, the gold trending is important, speaking to the same phenomenon Netflix, Hulu, Disney+ and other SVODs are witnessing.

A lack of new hits.

It’s a problem whether you’re running a subscription streaming video platform…or a contemporary music station.

Is it a problem for the music industry – and by extension, radio? Ultimately, yes. Every form of mass pop culture and art needs to feed the beast in order to become – and remain – mass appeal.

And that requires an influx of new hits – movies, Broadway shows (when they come back), and of course, music. Without new artists making new hits, you’ve got a music business treading water on its equivalent of Seinfeld reruns – Classic Rock and other catalog material.

music business treading water on its equivalent of Seinfeld reruns – Classic Rock and other catalog material.

The TV business cannot survive on programming featuring the same four people gabbing about “nothing” at Monks Cafe any more than radio and records surviving on the Led Zeppelin catalog.

This data suggests a new music drought – at least in terms of emerging, successful mass market artists and songs breaking through. Radio pros have watched Alternative, Top 40, and other formats reliant on fresh new hits atrophy.

So, what’s the solution?

Returning to Netflix’s dilemma, they’re addressing it with new content development. The hope is that as COVID wanes, more and more production studios in the U.S. and around the world will ramp up activity in the coming months.

But it takes serious capital to make this happen. According to Deadline’s Peter White, Netflix will spend a whopping $17 billion (with a B) on new content this year.

And that’s just Netflix.

So, is there an analogy in the music and radio industries? An injection of serious money – the audio equivalent of what Netflix is laying out – is likely out of the question for record labels (although they enjoyed a successful 2020).

Maybe distribution and marketing have a little something to do with it.

I hear many critics – in the music and radio industry, as well as “civilians” – tell me that new music and new artists aren’t as good as they used to be.

I hear many critics – in the music and radio industry, as well as “civilians” – tell me that new music and new artists aren’t as good as they used to be.

That everything today sounds derivative of what came before it. That rampant sampling of gold songs in Hip Hop records speaks to a lack of ingenuity and talent.

Sorry, but I’m not buying that.

An hour on YouTube and TikTok suggests that’s not it. There are plenty of multi-talented musicians out there, unable to connect with a delivery method that effectively reaches mass markets.

So, maybe it’s not a content or creative problem, but is instead a distribution and a marketing problem.

Before there was the “long tail” of audio streaming, radio and the music industries worked together to build brands and promote hits.

And because everyone listened to the same radio stations across the country, and because most of them were playing similar playlists, we all were exposed to new music and new artists at the same time.

While progressive rock FM stations took big risks in the late ’60s and early ’70s, the fact is, breaking out in radio has always been a long, laborious process. To get a record added on WABC, WLS, KHJ, or CKLW was like crossing a musical Rubicon.

While progressive rock FM stations took big risks in the late ’60s and early ’70s, the fact is, breaking out in radio has always been a long, laborious process. To get a record added on WABC, WLS, KHJ, or CKLW was like crossing a musical Rubicon.

But once one of these “influencers” committed to a new song and/or a new artist, it wasn’t long before the entire country was singing along.

Ask any music fan about new artists they’ve discovered this year, and you’re likely to build a list with few duplicates. That’s because we’re all streaming different stuff.

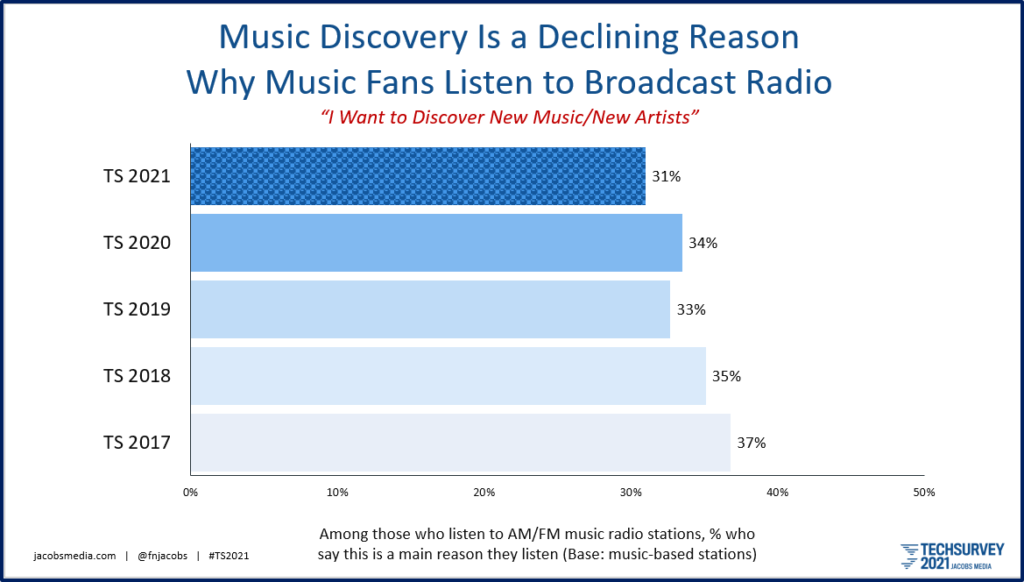

More and more, consumers are not looking to the radio to find out about new releases and breakout artists. When we ask radio listeners why they tune in stations, fewer and fewer say a main driver is new music discovery:

Yet, just about everyone still listens to radio. There’s a reason why radio’s biggest companies are using their national scale to promote their podcasts via their branded apps. The megaphone still works.

As we climb our way out of COVID, the entertainment bounceback promises to be strong. Consumers want to get their lives back, to get out, to start going to concerts again. The second half of this year could be amazing.

But then the systemic problems that have plagued the two industries in recent years – a lack of hits and a screwed up, multi-faceted distribution model will conspire to slow the development of superstars and their musical art.

Radio and records – as we used to say – were stronger and healthier when they worked together and fed each other’s seemingly insatiable needs. Is this “a moment” when both sides sat down at the table and reviewed everything – streaming fees, co-promotion, concert and merch marketing, local festivals and tours, web and on-air content, artist and music experiences fans can’t get anywhere else.

In our post-COVID world, these are conversations that should happen again.

Just not on Zoom.

- What Is It With Female Robot DJs? - April 30, 2025

- Why “Dance With Those Who Brung You” Should Be Radio’s Operating Philosophy In 2025 - April 29, 2025

- The Exponential Value of Nurturing Radio Superfans - April 28, 2025

Fred,

A great thesis for new formats and presentation? Audio is hot yet radio is stuck replaying the same safe songs for a ever shrinking cumulative audience.

If we want different results, it’s time to be the change from the same old song and dance.

Appreciate the comment, Doug. Thanks for weighing in.

I was starting to believe that I just wasn’t looking in the right places for new music for, THE EVERYTHING SHOW. Yesterday I spent more than two hours, and I do that daily, looking for new releases and came up with 4 Titles that I could give at least one play.

I know you put a lot of time into picking out those songs. It’s called curation, and it sounds a lot better than machine-picked songs. Thanks for the comment, Dan.

I don’t even know why I still pay for Netflix. It’s been sucking air for what, almost two years now. I’d say 80 percent of the ‘new’ content is foreign language. I get it, not that much being made and they want to appeal to other countries, but if I want to read, I’ll buy a book. Subtitles are ok, but after a while, I just want to watch something, not read something. There’s a first time to say everything, and here goes, “The hits just don’t keep on coming.” I’ll show myself out.

Inertia has a lot to do with it. With $17b, they should be able to come up with lots of new hits. Meantime, what are you going to do with all that money you’re now saving?

Buy a ticket on Space X to Mars.

🙂

Around 1990 there was a huge shift downward in new title record sales compared to catalog sales. While “the suits” loved to blame Napster, I was asking myself “what changed?” The answer came when I couldn’t find any live music in the San Francisco Bay Area to demonstrate what music and my career were all about to my young daughter.

Local live venues used to grow the artists who became hit makers. They learned as an unknown in front of a live audience what kinds of songs and performances engaged the crowd and what kind left them yawning. Covering other people’s hits was part of the story but young songwriters also slipped in their own compositions and learned from the crowd’s reaction.

So how do we fix this now that they’ve “paved paradise

and put up a parking lot?”

As far as I can tell, it’s starting over from the beginning. Something interesting that doo-wop, progressive jazz, folk music, hip hop and the San Francisco rock scene all have in common is that each began with living room concerts. Motown’s early artists were also part of a local living room concert scene.

As some of the artists began to develop a following, they started attracting young managers and promoters who would rent a venue and sell tickets. Local record labels would record them, and local stations would play the records provided the local stores were telling them people were actually buying the records. Nearby stations would consider airplay and the artist would grow a market city by city. Eventually, they would get picked up by a major label or their local label might even become a major label.

There are the seeds of this kind of activity in many areas of the country. (world?) Radio could probably help the process along.

I really appreciate this thoughtful comment, Bob. It makes you think about how, somewhere along the line, there became too much of an emphasis on “What’s in it for me?” Of course, that’s always part of every equation, but taken too far, you start losing sight of the fact that there really is a process that requires nurturing on the front end from ALL the stakeholders who will benefit come “harvest time.” We’re all in it together, but if we never look up from the balance sheet, we’ll never understand why it keeps trending downward even as we stare at it.

Thanks. Our music business is the perfect example.

Bob. truly appreciate this thoughtful response. Two of your lines really jumped out at me:

“Starting over from the beginning” and “Radio could probably help the process along.” Yes, on both counts.

And here were at precisely “The Greatest Re-Set of Our Lives” – RIGHT NOW. It’s the perfect time to rewrite the rules.