Let’s cut to the chase, OK? You know those six words well:

“We’ll be right back after this.”

(I know – it’s technically seven words because of the contraction.)

If you believe commercial radio’s ad model is broken (and it is), let’s look at the rest of the world. If subscriptions (OK, public radio peeps – “membership”) were the “Holy Grail,” then why would everyone from Netflix to Spotify to YouTube to your favorite podcast be experimenting with new architecture that includes blowing up the “commercial free” standard to start playing (audible GASP!) ads.

You can hear consumers loudly shouting out that collective “NOOOOOOO!!!!” in unison. But no matter, all those Chief Revenue Officers are busily at work, trying to devise commercial configurations we somehow won’t notice.

But we have and we will.

That was one of the five big takeaways Seth Resler had from Podcast Movement. As he explained in a recent blog post, an ongoing discussion in multiple panels revolved around the nuances of commercial content. That’s right – a major topic at this seminal podcasting community event is trying to figure out better advertising architecture.

That was one of the five big takeaways Seth Resler had from Podcast Movement. As he explained in a recent blog post, an ongoing discussion in multiple panels revolved around the nuances of commercial content. That’s right – a major topic at this seminal podcasting community event is trying to figure out better advertising architecture.

Programmatic buying and selling, produced spots vs. life reads, and my favorite question: How many commercials are too many?

That first issue could be the key to unlocking revenue, but it could also threaten brand safety. And of course, just about everyone’s research shows that host-read ads are most acceptable to listeners.

But it’s this last issue – spot loads in podcasts – that is most troublesome. While the commercial irritation factor of commercials is very low for podcasts, Edison Research shows it doubling in recent years. And NuVoodoo research also reports on numerous complaints about commercials in certain podcasts.

Of course, the whining pales in comparison to radio and TV, perceived to be far more commercially bloated than podcasts. As Seth noted, “The problem with ads may not be the content or tone, but that there are too many commercials. Even if you love an ad, its constant presence may irritate listeners.”

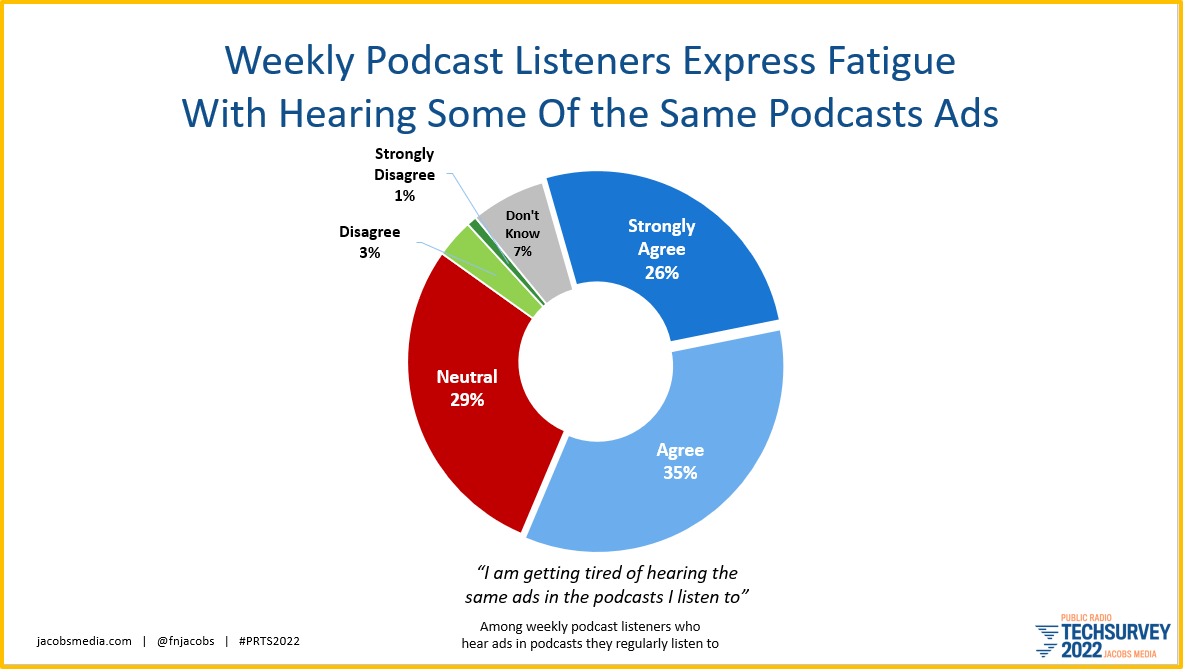

And he’s right. Our most recent Public Radio Techsurvey picked up on repetitious ads in podcasts. Hello, Zip Recruiter.

Netflix is about to roll out its “commercial-supported” version, a cheaper tier ($6.99/month) for more frugal consumers to consider. Remember, it wasn’t that long ago when they were mailing CDs in red envelopes. Netflix, like so many other media/tech companies is not afraid to throw spaghetti at the wall. It will launch next month.

According to The Verge, Netflix Basic will initially be available in 12 countries, including the U.S.

But there’s a catch – several of them, in fact. Some Netflix content won’t be available to these discount subscribers. Additionally, video quality will be capped at 720p/HD. What effect will that have on the viewing experience? I’m not an engineer, but it could be another reason why this service is so cheap.

Then there’s the minutes vs. units kerfuffle, something every radio programmer has experienced when wrangling with a local sales manager. The Verge’s initial reporting stated Netflix Basic would only run 5-6 commercials an hour. That later got clarified to 5-6 minutes per hour. Given that Netflix Basic ads will have a duration of 15-30 seconds each, you can do the math.

How will this discount version of Netflix perform for the company? Netflix describes it as “pro-consumer,” insisting that commercial clusters will be scheduled during “natural breakpoints” in shows and films. They will occur before and during video content.

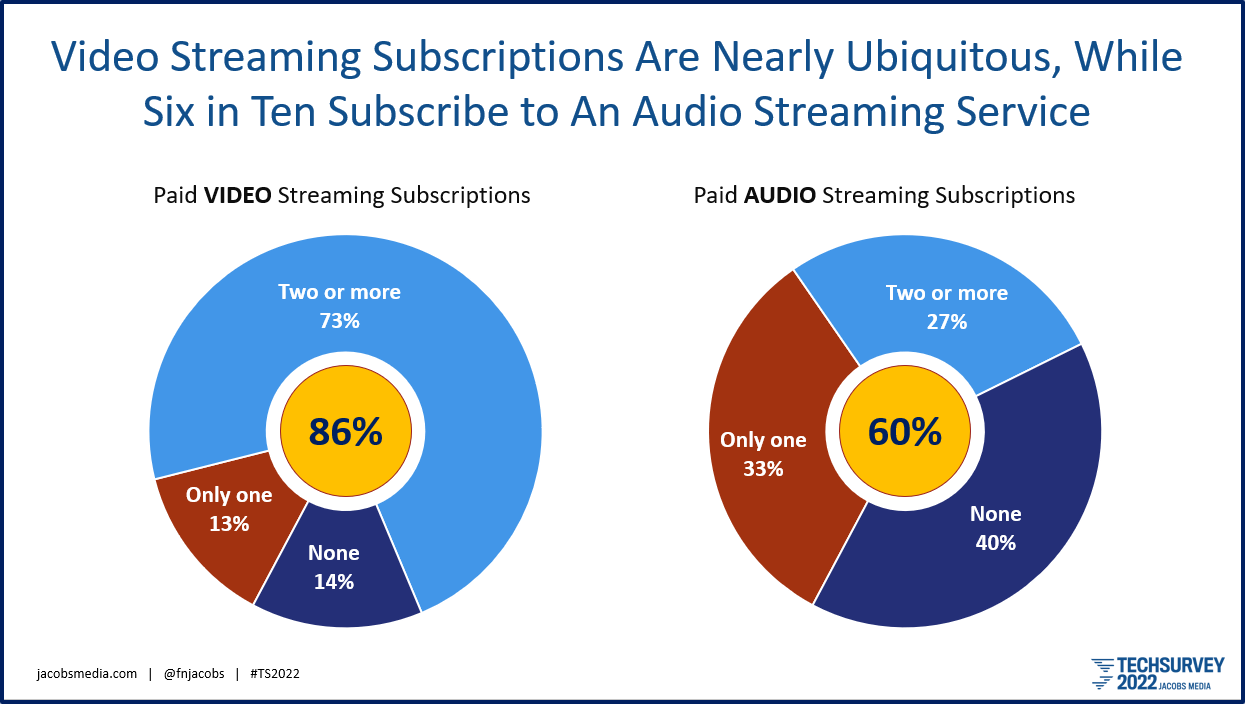

We’ve talked before about the “subscription economy” before and Techsurvey 2022 tells us close to nine in ten (86%) core radio listeners subscribe to at least one video streaming platform; six in ten (60%) pay a monthly fee for an audio streaming service:

Suffice it to say, this is big business, yet another reason why Netflix needs to retain thriftier households no longer interested in paying for the premium service, as well as those who have never subscribed.

And that brings us to commercial radio’s business model. These days, public and Christian radio would seem to have an advantage. Beyond sponsorships and underwriting announcements, stations in these categories raise money during “pledge drives” (public) and “shareathons” (Christian), appealing to their most loyal listeners.

And that brings us to commercial radio’s business model. These days, public and Christian radio would seem to have an advantage. Beyond sponsorships and underwriting announcements, stations in these categories raise money during “pledge drives” (public) and “shareathons” (Christian), appealing to their most loyal listeners.

And it generally works, at least financially. But there’s a rub. While these drives tend to be successful, they are off-putting to the most avid and most generous listeners of these stations, many of whom tune elsewhere during these multi-day fundraising campaigns. It’s a gross understatement to concur the listening experience during “pledge” leaves much to be desired.

Commercial radio, on the other hand, has not been able to successfully diversify its business model. The “best practice” (and yes, I’m being sarcastic) remains especially for most music stations is two long clusters an hour crammed with :30 and :60 ads. Most consumers find commercial radio’s advertising platform annoying at best, repellent at worst.

So how do financial analysts who specialize in media and technology handicap broadcast radio’s chances to not just survive, but to thrive in this increasingly competitive marketplace?

Last week at the NAB Show in New York City, a couple hundred of us took an excursion to Bloomberg’s stunning headquarters on Lexington Avenue. I cannot even begin to explain just how incredible this space is – an amazing media facility.

I don’t know how well occupied the workplace’s 29 floors is, post-COVID, but I can tell you that if I worked there, I’d make every effort to show up for work. The building has energy, and the “Bloombergians” seem upbeat as they go about their business.

The NAB held a couple sessions at Bloomberg, in addition to talks from two of their main anchors, Carol Massar, long-time anchor of “Bloomberg Businessweek” on both TV and radio. She told us how integral radio is to the company, and to her career path.

More sobering words came from Paul Sweeney, co-host of “Bloomberg Surveillance” and “Bloomberg Markets AM” airing weekdays on Bloomberg Radio. He discussed his concerns about radio’s continued viability in a sea of audio outlets that are more in-demand: podcasts, streaming, and satellite radio.

But Sweeney also underscored something we’ve talked about a lot this year on this blog, and every chance I get to in speeches, presentations, and on panels:

The power of personality, especially on the local front.

Sweeney mentioned his loyalty to Howard Stern, and his subscribership to SiriusXM. But he added that when Howard finally hangs up his headphones, the Bloomberg anchor will stop paying for satellite radio.

And then he surprised some of us when he talked about how much he enjoys listening to Pierre Robert on Philadelphia’s WMMR. Sweeney told us he goes out of his way to listen to the affable Robert when he can.

And then he surprised some of us when he talked about how much he enjoys listening to Pierre Robert on Philadelphia’s WMMR. Sweeney told us he goes out of his way to listen to the affable Robert when he can.

On the one hand, Sweeney criticizes radio for having lost its “est” – its USP, its superpower. But on the other, he points to the incalculable value of a friendly, hometown talent who curates his music and always has a lot to talk about.

During Q&A, I tested the waters a bit, asking Sweeney whether he’d be willing to pay $2-3 a month for the pleasure of listening to Pierre (and WMMR) commercial-free, along with six song “skips” per hour. (By the way, this is similar to the model Bauer Media is experimenting with in Europe, discussed earlier this year in this blog).

The usually glib Sweeney paused and thought about it.

He didn’t say “yes” and he leaned “no.” But this question of “business models” and “how do we pay for it?” is especially salient in 2022, as we possibly approach the potential of a much-feared recession.

Sweeney’s hesitancy suggests to me that consumers – even the experts – are open to different delivery and distribution models, many of which will be hybrids of the subscription models we’ve gotten accustomed to. It also underscores the increasing value of personalities – especially local ones – in the radio success equation.

Netflix is testing the waters with its new ad plan. Like so many tech experiments, this one could end up going in many ways. Some subscribers currently paying $19.99 or $15.49 a month for their Premium and Standard tiers mind end up leveling down to the new Basic with Ads package.

Netflix is testing the waters with its new ad plan. Like so many tech experiments, this one could end up going in many ways. Some subscribers currently paying $19.99 or $15.49 a month for their Premium and Standard tiers mind end up leveling down to the new Basic with Ads package.

Or Netflix might end up attracting dropouts, or even better, luring new subscribers to the service.

But they won’t know until they launch and market this package, as well as other services and plans they try. Most tech companies – Spotify – is on the extreme end – are always launching new services, equipment, plans, and deals – hoping to find “the answer.”

Broadcast radio – commercial, public, Christian – might help itself and offering its audiences a service by taking a flyer on new business models, rather than fearing the ramifications of a change.

You never know. These experiments might lead to other innovations. And they might actually do something about solving a fundamental problem.

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

- I Read The (Local) News Today, Oh Boy! - April 15, 2025

“Broadcast radio…might help itself and offering its audiences a service by taking a flyer on new business models, rather than fearing the ramifications of a change”

Now THAT’S comedy!

I couldn’t agree more about the length of radio spot breaks. So why was music on AM so successful for years with shorter commercial breaks than today?

Baseball used to do the same thing (on radio and TV).

As a former traffic manager I understand the sales vs programming debate. I can’t count the number of times sales would ask if there is an “avail” at “x” time. Being more loyal to programming it was always fun to bring the PD (now a content director) into the conversation.

It seems that streaming platforms and services are experiencing a situation very similar to that experienced by radio in its early days.

History says that at the beginning of the 20th century, radio equipment manufacturers and retailers operated most radio stations, and used them primarily to promote radio sales, rather than to profit.

Radio stations at the time were seen more as an investment to entice households to purchase radios, and less as a standalone revenue stream.

Between 1919 and 1922, radio stations began to ramp up their offerings, and it became the norm to broadcast continuously. Station owners began obtaining business licenses and seeking ways to make the medium self-sufficient.

For a while, the average radio station existed entirely without commercials. Thus, radio advertising came to be. However, as time went on, people started to object less to promotional material on the airwaves, and regulations appeared to govern the appearance of ads.

The first recognized form of radio advertising came in early 1922 when AT&T began to sell toll broadcasting opportunities, in which businesses could underwrite or finance a broadcast in return for having their brand mentioned on air.

Later that year, the New York radio station WEAF was the first station to run an official paid advertisement. These forms of radio advertising become more and more popular, leading stations into the golden age of radio.

Listeners gradually grew accustomed to the presence of advertising in radio.

Doesn’t this situation sound familiar to you?

Now, history seems to be repeating with the advent of streaming services and platforms.

At first, people are happy to find no commercials or to be exposed to very few. But that model is not viable if you want to achieve good billing, so the number of commercials will start to grow, as happened with radio, and those companies will have to figure out how to present them in such a way that they do not drive listeners away.

That is, the same problems facing radio today.

In times like the present, when everything is immediate, many times we don’t stop to think about what history has taught us, but life definitely moves in cycles.

Yes, audio platforms currently have the advantage over radio in not having as many commercials, but it seems that they will be affected just as much as today’s radio.

Two thoughts. You mention how the pledge drives and share-a-thons in public and Christian radio tend to be successful, while also driving away some of the most generous listeners. The fact that these drives are successful with these “generous” listeners suggests they understand that’s part of the cost of doing business, and that they’re ok with it. The fact that they tune out is obviously not ideal–and ways to keep them tuned in should certainly be explored–but it may also just mean they “gave at the office.” That is, they’ve made their donation and have no need to continue listening while the drive continues, much like the public radio listener who supports their local station, but streams an out-of-market station during the drives in order to continue listening to their favorite programming.

Other thought has to do with Netflix capping the video quality on the lower-tiered service. It made me think of two of my favorite shows, The Simpsons and The Honeymooners, the former of which is done in the highest quality available, and the other at what is now the lowest. And yet I never watch Ralph, Alice, Ed and Trixie and think, “I just can’t get past the horrible quality this show was recorded in 70 years ago.” Netflix may have started with mailing videos, but the empire really rose due to exceptional programming people wanted to see. I’m not suggesting video quality doesn’t count (to some more than others), but if a show sucks, the only difference the same show will tell me in higher quality is the show CLEARLY sucks.

Gotta be honest…if I’m paying for a television streaming service, I want it to be commercial free. So, yeah, I’m shelling out the premium price for the services I want. I just keep the number down, or bundle so I can get a good deal.

As far as radio stopsets are concerned, I never got the concept of the bowtie clocks – it’s a disservice to both client and consumer to play ten spots in a row. (And I’ve worked at stations that did.)

Finally, in regard to on-demand versus on-the-air, don’t tell me that people can get the weather, traffic, news and emergency information on their phone, so why listen to radio. Do you think the audience is psychic??? If they’re not listening to a source warning about a tornado, HOW WILL THEY KNOW A TORNADO IS COMING? Yes, there are alerts that pop up, but not all folks are plugged into that, especially if the alarms also go off about emergencies in another part of the state (the cry wolf factor.)

There’s a lot of online content out there…do you think the audience has the time to wade through it to get to what matters to them? If we broadcasters do our job, we’re telling them about what interests and affects them in their community. If they learn they can rely on us, we’ll get their business again.

Lots to unpack here, Dianna.

First, we agree. If I’m going to pay SVOD, it’s going to have to be sans ads. And what’s the point of bandwidth limitations like the ones Netflix is packaging in to their $6.99/month package. Ugh.

Second, the “bowtie” format is all about PPM. The notion here that dividing the load that now bloats two stopsets into three will ultimately diminish the ratings. That’s because the “recovery time” even after a short break of ads is too great. So, we’re stuck with two stopsets. They run where they run to maximize the chances of getting credit for all four quarter-hours given Nielsen’s 5 minute rule.

Finally, I wasn’t suggesting time and temp are a waste of time. Maybe doing them with 1985 frequency and repetition could be rethought. Obviously, that’s on a “normal” weather day. When something unusual/bad is coming, all bets are off – stations should be informing their listeners as often as necessary.

And to your last point, a great host who has something to say is always going to be more interesting and a better companionship than a podcast or a playlist.

I hope this addresses your questions. I always appreciate hearing from you, Dianna.

Great piece Fred! And timely!

Re the “advantage” pub radio has in airing both underwriting, and doing on-air fund drives, I’d remind us of the built-in disadvantage that public had with regard to underwriting language; no call to action, no comparative, no superlative, no promotional language. Pub radio can NEVER “run the creative” from an agency. And that disadvantage has been described as a 50% to 75% handicap even for highly rated public stations. So in terms of comparisons, the membership model doesn’t even get them back to near break even against their commercial counterparts. I supposed you could say that the off-putting sophomoric and idiotic creative of many agency radio spots is a handicap (snicker), but not enough to put a dent in commercial radio’s dollar advantage.

Still, your bigger point is taken. Experimentation with business models is a must for radio. And yes, I do think that both commercial and public (to the extent it’s legal) will try some of what the other guy is doing.

A lot to think about here, Tim. The public vs. commercial dynamic is fascinating. You’re right that creative dictates are limiting factors. But the low-key style of public radio’s “credits” works in contrast to the overhyped “creative” on commercial stations. And thanks for underscoring my main point – neither public nor commercials operators can afford to take a business as usual approach to revenue generation. We’ve got to experiment with other models or we’re fated to age poorly. I appreciate the comment.