It’s one of those things about radio that simply annoys the hell out of listeners – especially the loyal ones.

It’s when a DJ “disappears” from the airwaves with no notice or explanation. There is no last show because management doesn’t want to take a chance the now-unemployed air personality will go rogue during their famous final studio appearance.

Rarely will you see the net effect of these abrupt changes in the ratings or audience research. Sure, ratings or even P1 levels might shift as a result. But when listeners only get a voice on social media, it’s easy for management to pretend it didn’t happen.

I moderate a ton of focus groups for radio stations, so I hear the emotional feedback from audience members all the time. And when there’s no official explanation, urban legends take over, almost always making talent the victim and positioning management as evil, uncaring, and cruel. While the latter may indeed be the case more often than not, the bosses do not have to be the bad guys.

The problem is, whether station management, the researcher, and the consultant will admit it or not, a jock with just a 2-share has likely built up a bigger following than most gave them credit for. It may not be enough to satisfy the station’s ratings and sales goals, but it’s something.

And the result of a favorite talent vanishing from the local airwaves and the website can be hurtful to listeners, making them feel even more disconnected and even estranged from station they once called their favorite.

And the result of a favorite talent vanishing from the local airwaves and the website can be hurtful to listeners, making them feel even more disconnected and even estranged from station they once called their favorite.

When they’re botched and poorly planned, sloppy departures send a message to remaining staffers the same shabby treatment will likely happen to them. Of course, it also can cause brand erosion.

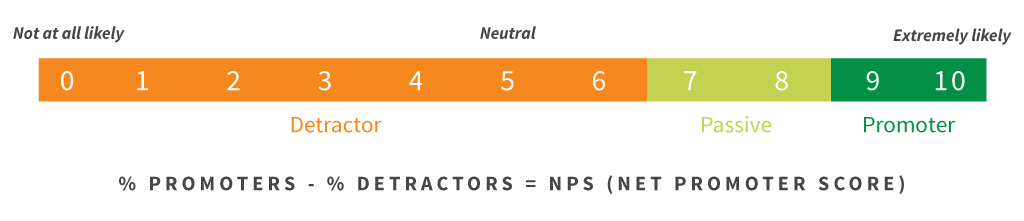

We see the effect in Net Promoter Scores – the degree to which listeners recommend stations to others – every year in our Techsurveys. You’re not likely to tell your buddy at work good things about a station that mismanaged the exit of a favorite on-air talent.

We’ve been tracking Net Promoter in every Techsurvey, dating back to 2004. And these trackable numbers tell the story of radio stations, their highs and lows, their big moments, and their embarrassing ones. Like it or not, the audience is an emotional entity – they react to what they hear – and don’t hear – on the airwaves.

And when these cuts, RIFs, or layoffs happen abruptly and without warning, they can create blowback on social media, sometimes instigated by talent themselves. Management can comfort themselves with the knowledge these disruptions are only temporary, but why go through them in the first place? Is there a way to not only alleviate the vitriol, but perhaps pull off a more human transition, and even generate a little revenue at the same time?

That’s what Netflix – and other streaming platforms – apparently struggle with. We don’t exactly know what drives their decision to cancel shows prematurely before their intended endings. Obviously, the criteria has a lot to do with viewership, binging levels, demographics, and the degree to which viewers finish out seasons.

their intended endings. Obviously, the criteria has a lot to do with viewership, binging levels, demographics, and the degree to which viewers finish out seasons.

And TV critic Erik Kain is pissed off about it. In a new Forbes opinion piece, he avers that while Netflix has the right (and even the responsibility) to cancel its absolute losers, shows that actually aggregated an audience deserve closure – not just for the audience but for the producers who are likely to create more successful content down the road.

In “Dear Netflix: Give Your Cancelled Shows The Final Seasons They Deserve And Everybody Wins,” this aggrieved critic makes the case for that famous final season – or episode – that closes the book on our hero.

Kain contends that – just like radio – it often takes time to forge a relationship with an audience. But with enough episodes in the bank, even OK shows develop a following with their audience bases. It’s often like that on the radio, too.

Kain contends that – just like radio – it often takes time to forge a relationship with an audience. But with enough episodes in the bank, even OK shows develop a following with their audience bases. It’s often like that on the radio, too.

While he may overestimate his own importance as a viewer, there is something to be said for announcing the upcoming season is the last one for a TV show. At least in theory, that builds anticipation for the finale and a welcome end to a beloved – at least for some – show.

It’s a lot like that on the radio. What sounds like the better option? Radio’s abrupt ending where a host finishes out a show he, she, and listeners don’t realize is the last one, with a new person in the chair the next morning? Or learning that at the end of the week, the morning team will broadcast its last show on the station?

The answer is, it depends. There is talent that has earned the right to a final show – a chance to respectfully say goodbye while giving the audience a clear explanation about why it was time to part ways.

explanation about why it was time to part ways.

And there are hosts who simply can’t be trusted with the responsibility. There’s no reason for management to risk an embarrassing moment – or worse. There are advertisers, listeners, and a license to protect.

But more and more, I see talent gracefully saying their good-byes on social media, often diplomatically and even thankful for the opportunity. A final show might help them close out this chapter in their careers, while giving their listeners a chance to hear the last hurrah.

In some cases, there’s a financial upside, too. A mutually agreed-upon retirement opens the doors to a final series of shows that might attract sponsors and other revenue-generating opportunities. The Scott Shannon departure from WCBS-FM seemed to work that way.

Is there risk?

Of course. There always is when you’re dealing with personal taste, audiences, and talent. In the case of Netflix, another season (or even a final episode) is expensive to produce.

In radio, the potential costs are much different, especially if that last show doesn’t go as planned.

In radio, the potential costs are much different, especially if that last show doesn’t go as planned.

Ultimately, there’s an ROI to greenlighting that last show. To pull it off with class requires a steady hand, a great plan, and a lot of mutual understanding and cooperation.

That elusive final show carries risk. But it also can bring potential reward.

Closure isn’t always attainable, whether it’s that Netflix drama or that afternoon show that’s simple run its course.

It carries a creative challenge, because not all endings are happy ones. But it also can make a powerful statement about aa brand and its connection to the audience and the community.

A true finale is hard to pull off – on a TV network or a video streaming platform – or on the radio.

It’s never easy to say goodbye.

- The Hazards Of Duke - April 11, 2025

- Simply Unpredictable - April 10, 2025

- Flush ‘Em Or Fix ‘Em?What Should Radio Do About Its Aging Brands? - April 9, 2025

And then there’s the scenario where the entire staff are leaving. I remember when KJAZ Alameda flipped from jazz to Spanish-language in the mid-’90s, and nearly the whole roster were present for a final 3-hour show in the runup to midnight. Everyone contributed graceful, grateful remarks and tunes right up to the end (I recorded it). I didn’t hear anyone go off script, even though the owner’s sale of the station was quite controversial in the SF Bay Area radio community. I consider this the mark of true professionalism, a bright note on what was a sad day.

The whole staff is a very different story, John, as you well know. They can make magic under the right circumstances. Regarding KJAZ, you and others will probably remember that day always.

It really is a double edged sword. I do believe that listeners deserve to know that a talent is leaving the radio, but if he/she leaves on bad terms it can be counterproductive for the company.

But, even if they leave on good terms, it can also be bad for the talent involved in the layoff.

Many years ago my colleague and I were retiring from a station. Our bosses allowed us to continue on the air until the end of the month.

Obviously they were very aware of anything we could do or say against the station, even more knowing that we were going to a direct competitor.

One of those days a funny song came along, a novelty, and we aired it, just as we had always done with that type of songs. However, the bosses thought we wanted to make fun of them, the station and our audience. They got very upset and closed the microphones on us the next day.

It is not easy to handle these situations. In large part, it depends on the type of person leaving.

Tito, as you suggest, there’s a lot of moving parts – ownership, talent, and the real story. A lot can go wrong during this tense moments.

I’ve had experience with both and obviously I preferred to say goodbye. It always happened when I was the one who decided to move on. In those rare instances I got to play “The End” by the Beatles off Abbey Road which I’ve always viewed as the perfect way to sign off and end a relationship with the station and it’s listeners

How did you get a picture of my headphones?

We have cameras EVERYWHERE!

Great topic Fred. I would think in this age of VT’s where most shows are, or at least can be, recorded….it’d be easiest and safest to let someone record their last show or perhaps a last hour (and actually be able to pre-promote that during the other hours). Not ideal, but better than nothing and the ensuing rumours.

So much of how civilized a talent would be saying goodbye is how humane the company was telling him goodbye. There’s that.

The voicetrack option is a viable one, Pat. It certainly takes the guesswork out of the equation. Great talent can still make it sound sincere, authentic, and meaningful. And yes, it comes down to the company and who they really are. It is easy to be gracious when you hire talent. But how you fire them says much more about the kind of company you’re running.

We had a situation like this less than a year ago with a long time talent who was leaving. Everyone agreed the audience deserved to have a farewell from the talent. The talent handled it like a total pro, it was actually understated. Of course it all depends on the talent and the circumstance for the split with the station.

It’s never easy, Keith. In some ways, it’s easier to just cut talent off, not respond to audience queries and complaints, and move onto the next act. Credit where credit is due – to talent and management who find a mutual way to make it work so both sides can claim a “win.’

Fred, since I was there, and got it ALL on video, I can tell you first hand WHY Scott Shannon “retired” from CBS-FM in New York. It’s no secret that radio’s big three: iHeart, Cumulus and Audacy are all cutting costs and Scott was doing very well. The likelihood of his staying on, at his current salary, was slim at best. Being the iconic talent that he is, it was better to bow out on his own terms and on his own schedule. So he did. It was a somewhat awkward finish, since his last show before the Holiday break, for many years, was a moving fund-raiser benefiting the Blythedale

Childrens Hospital in Westchester County. He did a final in-studio show on Thursday 12-15-22 and then a final sign-off, complete with his signature “Bye Buckaroo’s” on Friday the 16th. It was classy and very dignified. WCBS-FM even re-named their studio in his honor! Every DJ should be so lucky.

We’re all adjusting to “radio today,” Art. Those fat contracts from the 80’s and 90’s are (mostly) a thing of the past. Despite whatever money distance there was, credit to Scott and management at WCBS-FM for finding a way to make it work.

I’m not an on-air personality, but will be retiring after 10 years as GM of my station, KMFA 89.5 Classical in Austin, at the end of this month. I’m honored that I will be the guest on our midday host Dianne Donovan’s popular weekly program, Classical Austin, usually reserved for musical artists, and we will talk about the last decade, what has been accomplished, and some of the great music we’ve loved throughout. Having seen CEOs “disappeared” from organizations, I am thrilled that won’t be the case here and I will have a chance to thank our wonderful listeners personally. Bonus: the show airs January 29th, which happens to be the 56th anniversary of KMFA’s first broadcast!

When Loren Owens left WROR in Boston after a successful run of many years, the last day was a party. His old air partner, Wally Brine, stopped by and many listeners called in. Near the end of the show, Loren told his audience he and the new owners had been unable to agree on a new contract and said “It’s just business.” He said that, come Monday, there would be a new guy on the show and he asked his audience to give him a chance.

Great story. I was consulting WROR at that time, and remember thinking what gentlemen Loren and Wally were. Just class acts.