If you’re a reader of research like I am, you know all about contradictions. Seemingly, we learn that something appears to be true in one study, only to be contradicted in the next report you read. Sometimes, an opposing fact can be found in the same piece of research.

If you’re a reader of research like I am, you know all about contradictions. Seemingly, we learn that something appears to be true in one study, only to be contradicted in the next report you read. Sometimes, an opposing fact can be found in the same piece of research.

There’s no fault in feeling confused or even disoriented by the “findings” we read. Most journalists aren’t researchers themselves, making it more challenging for them to discern truth from balderdash. And then there’s methodology – who the researchers talked to, the interviewing technique used, and the timing of the field work itself. All of those variables – and more – can impact a survey itself.

And so I’m thinking you may walk away from today’s blog post with that looming feeling of hypocrisy we often get when consuming the news, scrolling social feeds, or even participating in conversations with friends, colleagues, or family members. “Getting to the bottom” of something has become increasingly more tenuous for most of us.

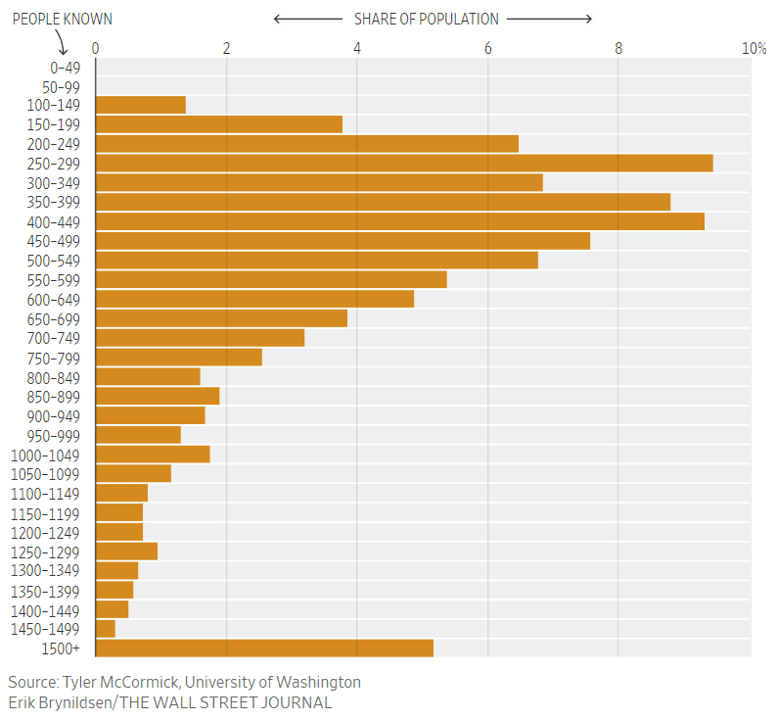

Let’s start out with the basic premise: the average person knows 611 people. (Fortunately, we don’t have to invite them all to our weddings and Bar Mitzvahs.)

How do we know this? The Wall Street Journal reported last week that statistics and sociology prof at the University of Washington, Tyler McCormick, has done the math.

As Josh Zumbrun reports, Professor McCormick’s tracking technique is highly unusual and even provocative. Utilizing a “Freakonomics” methodology, he and two other academics asked respondents how many people they know with common names – like Michael, Stephanie, or James.

The name Michael comprises about 1% of the U.S. population – or roughly 3 million people. Thus, if the number of folks you know named Michael represent 1% of your acquaintance base, the math does itself. If you know 5 people named Michael, the professors can extrapolate that you probably know 500 people.

To focus the quality of their estimates, the researchers used a dozen names to check their math. Along these same lines, another research team from the University of Florida used the same technique on the people you know who are, say, widowed, have diabetes, are Native American, and other demographic factors to statistically refine their results.

Here’s how their chart breaks it down:

But here’s the kicker:

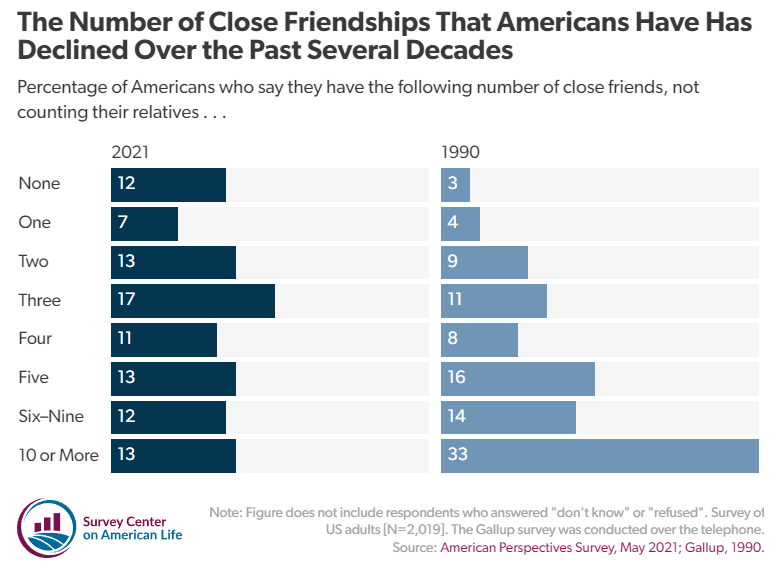

We may know hundreds of people but we’re only close to three or fewer of them.

Findings from a May 2021 research report called the American Perspectives Study confirm it. In fact, the number of close friendships we have has decreased over the past 30 or so years, despite the illusion of posses of friends we see all over social media:

What contributes to most of us having fewer and fewer friends? Of course, COVID is in the mix, along with the separation it caused. But journalist Daniel Cox points to the fact Americans are marrying later in life, delaying having children, and are more geographically fluid – all factors contributing to social isolation and loneliness. Let’s also figure in political polarity and the rise of anger, making it harder to have associations with people “on the other side.”

And how about this? Cox says, “Americans are now more likely to make friends at work than any other way – including at school, in their neighborhood, at their place of worship, or even through existing friends.”

Not if they’re barely showing up at their workplaces! WFH is undoubtedly another reason we are more apart from each other than ever.

And a new survey reported in Study Finds notes this trend has become even more alarming when you consider the average person spends just four hours a month hanging with friends. And more than a quarter of adults in the survey says “friend time” has decreased this year compared to last.

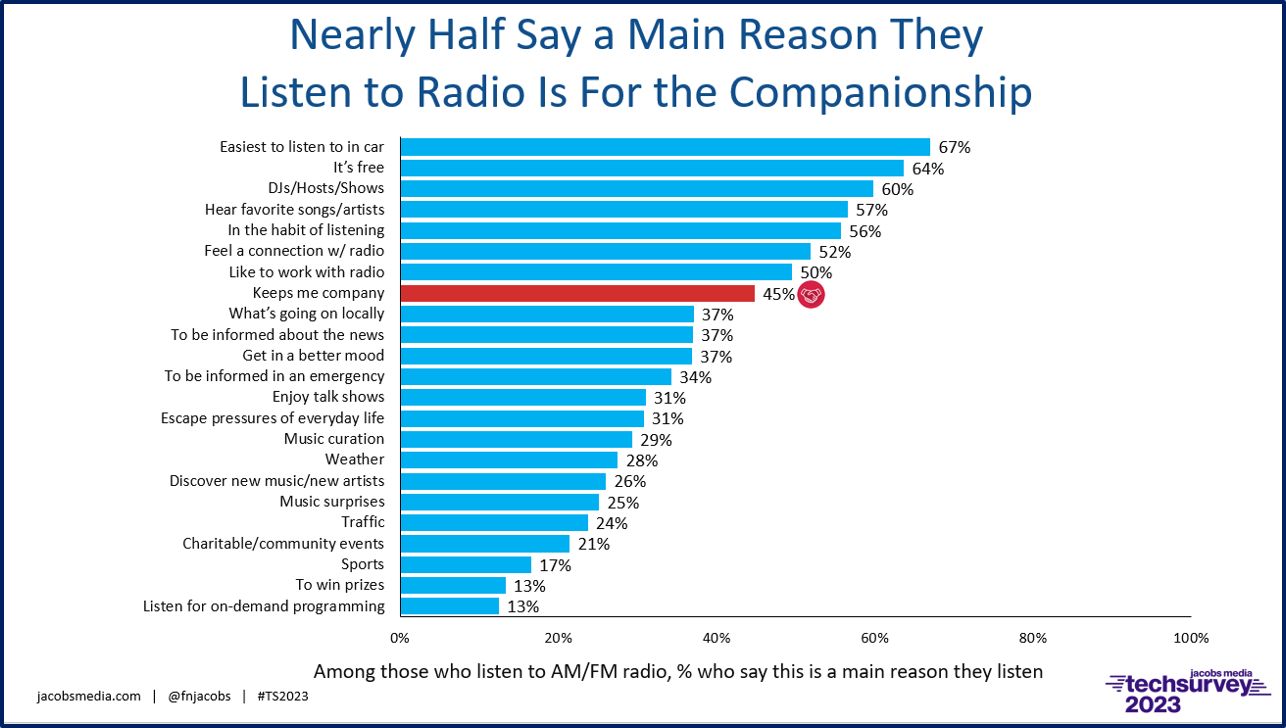

So, what does this mean to radio? Well, a look down the chart of our “Why Radio?” hierarchy reveals what many of us list as one of radio’s superpowers is providing companionship:

All told, 45% of our entire radio-centric sample says a main reason they listen is because stations and personalities keep them company. Companionship has always been a key component to better understanding audience motivations. And not surprisingly, more than half of women list it as a radio attribute. To that point, it’s not a surprise personalities like Delilah and Alan Almond of the classic Pillow Talk show here in Detroit made their livings off of female listenership and intense loyalty.

Earlier this year, iHeart head, Bob Pittman, reiterated his familiar trope about the essence of broadcast radio to the New York Post’s Lydia Moynihan:

“When people listen to their music collection they’re trying to unplug from the world – no on-air personalities, no information, no stories, no interviews – just music. When people listen to the radio, they’re joining the world. With (radio), they’re looking for connection, companionship and someone to hang out with, and that’s our purpose – even though we may also be playing music on some of our radio stations.”

The cynics among you (and I know you’re out there) may make the point companionship was a factor when more live personalities were on the airwaves. But Techsurvey is a current study taken among more than 30,000 listeners to the medium today. While it can be argued commercial radio isn’t as warm, one-to-one, and spontaneous today as it once was, today’s audiences still believe part of radio’s “job” is to keep them company.

And think how much higher radio could drive these scores if there were more personalities on the air after dark (when things can get awfully lonely). But keeping fans company when they listen to a personality on a radio station can happen at any time – during a long commute, an extremely hot or cold day, an emergency of some kind, the holidays – any number of events that happen every day.

In my radio listening across the country, and of course, online, I hear major contrasts between radio stations – often in the same market or even the same building. Some are continuing to deliver an “old school” experience with recognizable personalities engaged with what is going around with them. Other stations sound more mechanical, prerecorded, aloof, and disengaged. That doesn’t mean this latter group is erring or falling short, but it does mean they likely aren’t keeping anyone company, perhaps losing an opportunity to better connect with local audiences.

recognizable personalities engaged with what is going around with them. Other stations sound more mechanical, prerecorded, aloof, and disengaged. That doesn’t mean this latter group is erring or falling short, but it does mean they likely aren’t keeping anyone company, perhaps losing an opportunity to better connect with local audiences.

As Pittman points out, your albums, playlists on Spotify and on other DSPs cannot offer these attributes any more than a jukebox can provide a sense of connection. They are a utility. Satellite radio, however, can provide warmth and connection with its personalities and a number of their stations are providing just that – but without a sense of place.

I would love to see these scores for “keeps me company” rise in this year’s Techsurvey, as well as in successive years. They’re a sort of “vital sign” for broadcast radio, an indicator the medium continues to cut through – entertain, inform, and engage.

Situational awareness is an important attribute for on-air talent – a puzzle piece in the personality mosaic, enabling hosts to better relate with listeners and communities – whether the local sports team won last night, we’re expecting 12-14″ of new snow by morning, a famous local pizzeria is calling it quits, the prize of gas is going up again, or there’s a new song coming up by a station core artist. These are the everyday moments when a tuned-in air talent can relate and connect.

Situational awareness is an important attribute for on-air talent – a puzzle piece in the personality mosaic, enabling hosts to better relate with listeners and communities – whether the local sports team won last night, we’re expecting 12-14″ of new snow by morning, a famous local pizzeria is calling it quits, the prize of gas is going up again, or there’s a new song coming up by a station core artist. These are the everyday moments when a tuned-in air talent can relate and connect.

Can an AI DJ pull this off, even with the help of scraping local social media sites? Not yet, because programmers can’t just move the “companionship slider” on the algorithm. Nor can the technology show up around town to meet and greet audiences, be the PA announcer at the hometown team’s games, or host the annual Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals Radiothon.

Here’s another factor that plays a role in the power of radio companionship. We know many in the “cume” are going through difficult times, due in no small part to the arduous events of the last many years – divisiveness, the pandemic, and the litany of other stumbling blocks and setbacks people face every day.

Note that on that same “Why Radio?” chart are other telltale signs radio can play an even more important and unique role in their lives. Note that “mood elevation” and “escaping the pressures of everyday life” are each mentioned by more than three in ten respondents.

Your mileage will vary, meaning it’s different for every station. Some have been expertly aligning with listener needs and emotions for years, even decades. They understand there’s more to the game than pristine music logs, precision stopset placement, and error-free breaks.

And there’s another indication of the power of connection with a station personality. When you do your prep, take the time and embrace your audience. Many want to meet you. When you have the ability to keep them company and truly be part of their lives, they want to let you in. In commercial radio, these moments are memorable and indelible. In public and Christian radio, they are just as impactful, and they might even lead to a financial donation at one point down the line.

That’s what you see happening statistically on the “Why Radio?” bar graph. In real life, it’s something special that only a personality can bring to the listener/radio relationship.

Be a friend.

See how YOUR station stacks up for companionship, and hundreds of other measures in Techsurvey 2024, fielding in January. Info and registration here.

Yesterday, Westwood One/Cumulus Media released a great advisory, “How Audio Personalities Drive Advertising Effectiveness.” Pierre Bouvard and his team have made it available for free here.

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

“Entertain, inform, and engage.” Those three words should be posted directly in front of the microphone in every radio station on the planet. Every break should do at least one of those elements, and hopefully two or more. Sometimes information isn’t really entertaining, but it should be engaging and meaningful to the listener. Sometimes entertainment isn’t particularly informative, but it should be engaging and meaningful to the listener. Those three tenets rank right along side the public interest, convenience, and necessity.

Brian, thanks for giving us a smart way to think about it.

Caracol, the leading radio company in Colombia, and aware that radio is above all the great companion of the people, had as its slogan in the 80s “La gran compañía,” a play on words that referred to being a great companion to the audience and, at the same time, the largest radio company (in Spanish, ‘compañía’ means company and also companionship).

In the 90s, feeling that the slogan could be perceived as too ostentatious, the slogan was changed to “Más compañía,” a friendlier way to present that positioning image.

TIto, it is fascinating that companionship became part of the overall positioning for the company. Thanks for sharing this.

For radio it’s surely the same all over the world. Companionship has long been #1 for me, and this became even more important when I retired and no longer had the close interactions of the workplace. I listen to live, local radio a lot more these last few years, now on the receiving side of the mic. No-talent voice trackers get none of my time.

WCCO has historically been referred to as “The Good Neighbor”–officially for many, many years (sometimes including “…to the Northwest”), and unofficially even today. Similar branding is still used elsewhere–e.g., Manitowoc’s WOMT (as “The Lakeshore’s Good Neighbor”).