Today’s Throwback Thursday post takes us back to June 2015. Back then, we had launched a feature on the blog: Radio’s Most Innovative.

Each Friday, we highlighted someone who had done – or was doing – something innovative in the radio space. For more than a year, we saluted Dr. Demento, Andy Economos (the guy who invented Selector), Zach Sang, Dr. Ruth, Kurt Hanson, Art Vuolo, Delilah, Norm Pattiz, and many other true innovators and big thinkers.

One of my favorites is below – likely someone you’ve never heard of. But he brought truly innovative thinking to Spotify seven or so years ago when that platform was still trying to find its way.

I’m a believer that in order to be as competitive as possible with would-be challengers, you have to understand how they think. That was my logic going into my interview with Paul. He’s a brilliant thinker, and you’ll see some of his contributions to Spotify when you read this #TBT piece. – FJ

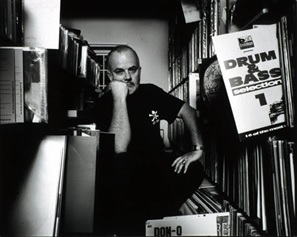

Paul Lamere is one of those oddities in the media and music business. He is truly a left and right brain kind of guy. He has expertise at writing code, but also has a strong appreciation and love for music.

That interesting combination of skills has allowed Paul to see the changing world of media and music consumption from a unique vantage point. He has been a leading thinker at Sun Microsystems, then the Echo Nest, and now Spotify.

So what is someone who works for a pure-play doing in “Radio’s Most Innovative?” Well, Paul is truly a music behaviorist and now he has big data behind him as a foundation of learning. He studies the way people use Spotify to better understand switching, usage, and perception patterns about music.

And when you look at Paul’s research and the data Spotify is aggregating, there’s a lot there for veteran radio programmers to learn that you simply cannot see in conventional callout or gold music tests. M Scores are the tip of the iceberg in understanding music consumption. Spotify’s data and the way Paul analyzes it is truly an eye-opening experience that any music programmer in broadcast radio can benefit from.

He has an amazing blog about the intersection of data and music consumption called “Music Machinery.” In today’s “Radios Most Innovative,” Paul talks about what he’s learned and how it applies to FM radio programmers and managers.

JM: What is your background and how did you end up here?

PL: I’m a frustrated musician. I’ve always been a big music fan going all the way back. But I’ve also been a software engineer since the beginning. I knew you could make a living creating software for Apple II’s and other early computers. I did that for lots of years but always had in the back of my mind the idea that I’d like to do something music-related because it is still my passion.

And so I found myself working at Sun Microsystems, which is a big computer company, and they had a research lab where I was pretty well respected. They asked what I wanted to work on, so I pitched a research project about trying to understand music, based on signal processing of the audio called “Search Inside the Music.”

I worked on that for about five years but at the end of the day, I realized Sun Microsystems was a computer company, not a music company. But there were some folks down the street at a startup company called the Echo Nest that were doing a lot of very similar stuff. So I packed up my bags and started working for them in 2009.

I’ve been being doing music tech for more than 10 years now, mostly trying to figure out how to understand music based on all the data that’s available, whether it’s how people are using the data, what the music sounds like, mixed signal processing, or what people say about the music, like reviews and all of that.

JM: The Echo Nest brands itself as “a music intelligence company.” How does that fit into what Spotify is all about?

PL: A big part of Spotify’s mission is to bring our listeners a good listening experience, and when you’re trying to keep millions of people happy, it’s challenging. There’s been a problem that Echo Nest had been working on for almost ten years that’s very similar to what I was talking about before with “Search Inside the Music.” It’s trying to understand music based on all of the data surrounding it.

For example, using cultural data like the tens of thousands of reviews written about a new album to get a sense for what, in general, the guys did around that album. Doing the same thing but with the audio itself, the signal processing around the audio, to get a sense of the strength of what a song actually sounds like so you can position it in the universe of music near other songs that sound the same.

The Holy Grail here is a music player that you just have to press the play button and it’s going to play the song that you want to hear next without you having to do much. That’s really important as you get to the more casual music fans, people who park their radio on one station. They probably don’t touch it for the next year and it gives them a nice series of good music and good talk. We’re trying to recreate that listening experience for different ty pes of listeners.

pes of listeners.

JM: So people who don’t want to work too hard to entertain themselves?

PL: That’s right. If you look at all the studies out there, the bulk of people are, at best, casual music fans. So they may know a few songs that are on the top ten and they may know a few songs from when they graduated from high school. But beyond that they’re kind of at a loss. So helping these people get more engaged with music is a big part of it.

JM: So let’s talk about your analytics, because the only data most radio stations have revolves around whether people like songs or not. That doesn’t incorporate context, mood, time of day, or any of those variables. Yet, the studies you’re doing actually slice and dice usage patterns which could help terrestrial radio get a better understanding of how consumers are actually looking at music.

PL: Yeah. Absolutely. But it’s funny; I think it really goes both ways. The radio industry really does understand how to satisfy listeners; they’ve been doing it for such a long time. But they have to satisfy 100,000 listeners at a time, while we are working with one listener at a time.

Some things are different but other things we’ve been rolling out in our product are dayparting and things like that, which you guys have been doing forever, and you do really well.

That being said, we have this amazing visibility into how people actually listen to music. We know who they are, how old they are, their gender, and where they are. We know every time they hit the skip button. All this data gives us a really detailed view of how people are listening to music instead of looking at sales figures where maybe that really popular artist has a big selling track because they’re famous but people aren’t listening to it. We can look at that data and say, “Well, people really are listening to this song over here and don’t listen to that song over there as much.”

JM: One of the beliefs that many people in radio have is that younger people are more song oriented and older listeners are more driven by artists. Does that assumption hold water with what you’re seeing in the ways that people actually consume music?

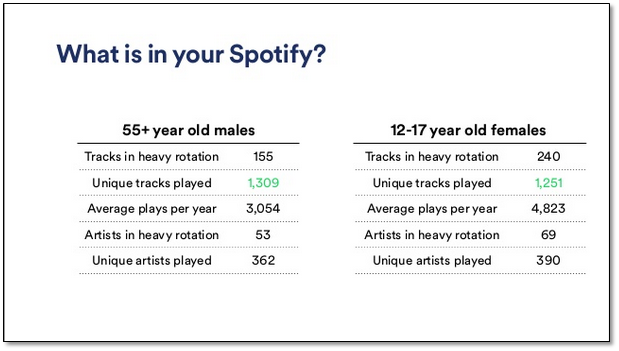

PL: We wanted to get a sense for how people’s music listening habits changed over the course of their first year with Spotify. And the thing we saw was the younger folks had quite a bit more tracks in regular rotation and older people tended to focus on a smaller cadre of artists. But it wasn’t as big as I was expecting, considering how music has moved away from the album toward single play listening. But yes, given about the same number of tracks played, there is maybe about 20% more of a variety in artists for younger listeners than for older listeners.

JM: Another data point is that the number of songs on an average iPod has increased about 50%, and yet, people are still listening to the same number of songs. What does that say to you about playlists and the whole idea of playing the hits?

PL: I think for starters there was a time, sort of the Napster period, where there was a sort of boom in music collecting. All of a sudden it was free to get as many songs as you could on your iPod. So I think a lot of music ended up on people’s iPods that they didn’t know and therefore didn’t listen to it. So we see this huge percentage, like 65%, of music on iPods that never, ever get played.

But I think that’s switching now. People tend to start with music that they know, and if the music services are doing their job right, they’ll help people find new music that’s similar to what they like and that tends to grow the number of unique tracks people listen to by maybe 20% to 30% per year. So I think we need to look at the data more to see how streaming is actually going to change how broad people’s listening is, and I think it’s quite a big broader.

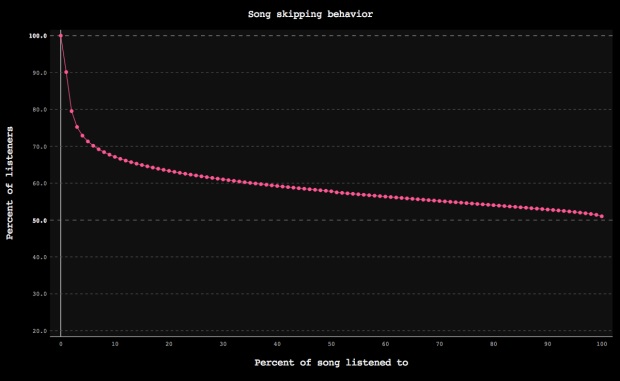

JM: You’ve written a lot about song skipping. Do you think this is analogous to button punching on a car radio? And what are you learning from studying song skipping behavior?

PL: I think one of the things about skipping is a lot of people now are listening to music on their phones, especially when they’re being active: driving, walking, running, or whatever – where they don’t look at the screen, but just hit the “next” button. So you may fire up a playlist and you know there are good songs on it, but the first ten songs are not doing it for you. So you just skip past them until you land on that song that you’re looking for.

And a lot of times, people are skipping because it’s a song that they just listened to or they listened to it too much in the last week or whatever. So we don’t put a lot of weight on skips in terms of whether people actually like or don’t like a song.

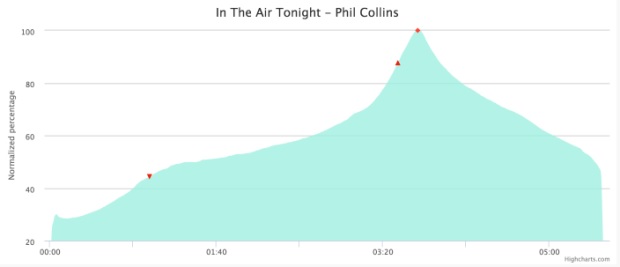

Another interesting thing beyond skipping is looking at “scrubbing” – when people move the slider around to start playing a song at a particular point. It’s a really interesting heat map of the parts of the songs that people like the most and least. So if you bring up a Skrillex song or some Dubstep, you can see exactly that build-up and the ensuing drop because everyone is scrubbing right to that spot in the song. And shortly after the drop, you can see everyone move on to the next song.

JM: So you’ve also talked about a shift in listening from genre to mood. How are playlists labeled “Chill” or “Party” or “Breakup” trumping genre playlists like Jazz, Hard Rock or EDM?

PL: On Spotify, people have created about 1.5 billion playlists. And when they do, it’s usually music that they like and they give it a title. We can look at all of these titles and see the ones that appear most often. And you’ll certainly see Rock and Jazz and all that, but if you look at the top 100 most frequently occurring titles, the majority of them are not genres but context – like “Workout” or “Running” or “Driving” or “Commuting” or “Studying” or “Focus.” So that really points to people using music very contextually.

Music is something that can happen in the background, so people are almost always doing something else. The music you want while you’re working out is going to be very different than the music you listen to while you’re studying. And we see people organize their music based on that as opposed to style or genre.

JM: So what would you say is the one stat or finding that maybe has surprised you the most about how people consume music online? Is there that one “Oh wow” moment where the analytics really rocked your world in terms of understanding music consumption?

PL: The notion that people will use their music player more as a browser and spend less time listening to full tracks before they go on to the next one, I think, is pretty interesting. The likelihood that somebody makes it all the way to the end of a song is 50% or something like that. That’s something that radio broadcasters can’t do anything about, right? They have to play that whole song all the way through even if half of the people are done after the third chorus.

That’s a really interesting dynamic in terrestrial radio, the fact that there is no “skip” button. Now you can always go to another station, but lots of people listen to music in the context of work or other activities where they don’t want to be hitting the station button. So if somebody hears a song that they don’t know, or may not think they like, they’re going to be listening to it. And that may happen, depending on the kind of radio station, three or four times a day where they’re being exposed to a song that they would’ve skipped on a music streaming service.

And that’s probably the biggest way to add new music to somebody’s regular listening rotation because people don’t like music maybe the first few times they hear it, but music grows on you. Being that you were almost forced to listen to it really changes how you perceive that song. So listening on a streaming service with the ability to skip music may shape the kind of music that we end up liking.

JM: How do you think your data applies to terrestrial radio programming? What could broadcast radio PDs learn from your data about music that maybe they don’t know now?

PL: Even just looking at simple things like demographics and region. So with somebody’s age, their gender, and where they live, we can find a whole lot. Now it turns out that everybody is listening to the greatest, you know, “Uptown Funk” or whatever, but if you look, if you break things down by these demographics, there’s quite a bit of differences there.

I think looking deeper into how these demographics affect listening is probably a good place to start. And I think we could also talk about one of the advantages that radio has is the really good mix of talk and music and getting that balance just right. That’s the kind of thing I think we have to learn more from terrestrial radio.

You may have seen where (Spotify) started to integrate podcasts into our app. I listen to podcasts all the time. You know, I work for Spotify, I love music. I also love information and I think most people are like that as well, where having a mix of music and talk is a good experience. So you can imagine someday morning drive may be a mix of music and podcasts or latest news. And that’s the kind of thing that terrestrial folks have been doing for years and years, and they seem to have done a pretty good job at it.

JM: When we conduct research for Alternative or Triple A stations, one of the big desires is an interest in new music discovery. Now that people have the ability to discover new music from an infinite number of sources, including popular channels like yours and Pandora, what role do you think broadcast radio can still play in music discovery? Or can it?

PL: So the role I think terrestrial radio has played very well, and continues to do well at least in some markets is to have a tastemaker or a curator; somebody who actually understands the music enough to program a radio station. You know the John Peel’s of the world who can find new music. And once a listener has listened to one of these DJs for a while, they get to really trust their taste. When they get a recommendation from a tastemaker, we’ve seen that carry a lot of weight in the past and I think we’re going to continue to see that.

And now we’ve seen a few big DJs being picked up by music streaming services because they see the human curator is going to be a big part of listening. So make sure you hang on to those folks before you lose them all.

JM: So invest in good people with great taste.

PL: Yep. That’s it. And then give them the freedom to actually program radio stations. Don’t just turn on your mix master or whatever program you’re using to program Monday morning. Figure out what’s actually good music to play.

INNOVATION QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“The more time you spend on an old idea, the more energy you invest in it, the more solid it becomes, and the more it will exclude new ideas.”

Brian Eno

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

That’s one perspicatious dude, Fred. Thanks for recycling him.

He is an excessively bright guy, John. I remember interviewing him and wishing radio had people like him.