Yesterday’s blog post about Mark Zuckerberg’s stated attempt to modernize Facebook by moving away from older generations of social media users elicited the expected reactions from many of you.

Frequent commenter (sadly, there are no “points” for that), Bob Bellin, conceded that Facebook may be confronting its “eventual cliff” because the future is always with youth. That said, Bob wondered about the validity of a new social media concept aimed at the upper-demo Facebook is apparently in the process of abandoning.

Boston-based consultant, Clark Smidt put it this way: “Is there something wrong with over-40 dollars?”

That’s a question many Classic Rock radio programmers (present company included) have pondered as Baby Boomers “age out” of radio’s 25-54 box. Bellin also noted the format has “managed to become relevant to younger listeners, despite the age of its music.”

But generational stereotyping remains a major part of radio research and programming strategies. Whether we define the population by age cells or with catchy labels, are we really applying logic and accuracy to our calculations?

The Atlantic writer, Joe Pinsker, suggests we end the practice of dividing up audiences with “standard” generational boundary lines. In “Gen Z Only Exists in Your Head,” Pinsker makes the case that generational analysis of data and trends is not only limited, but “stupid” (his word, not mine).

We’re been using generations in our Techsurveys (in addition to Nielsen-ish age groupings) for more than a decade. Most end users and audiences for whom I present these studies enjoy the groupings, even if social scientists can’t agree on precisely which years make up which generations.

In fact, Pinsker acknowledges Baby Boomers may be the only legitimate generational label because it was defined by an “actual demographic event” – the post World War II explosion of births. Beyond Boomers, the other gradations – Greatest Generation, Gen Xers, Millennials, and now the Gen Z sprawl are simply made up. They are also fluid because of the lack of agreement among social scientists about where to to draw the lines.

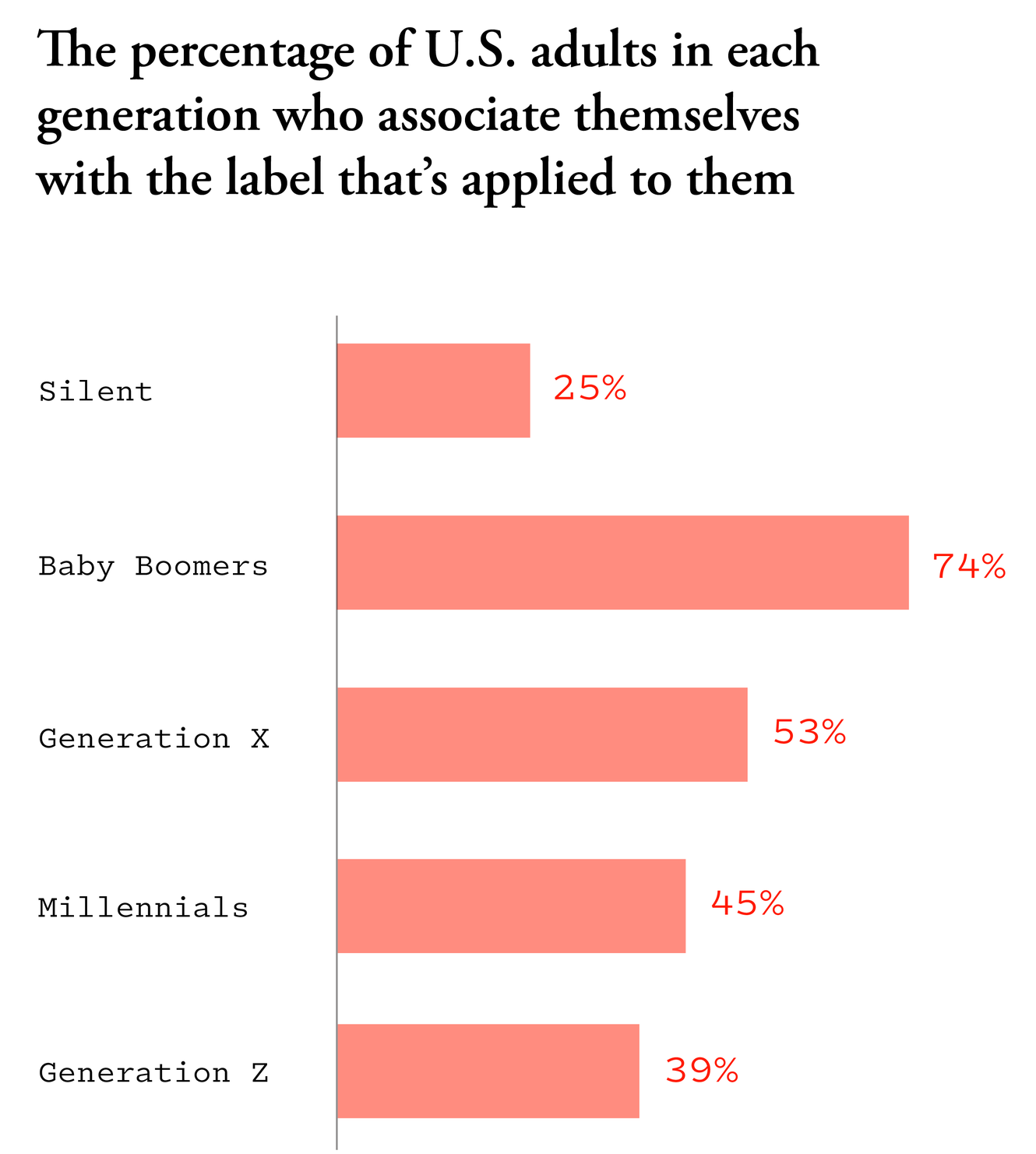

Even stranger, YouGov’s recent survey of American adults reveals that many people don’t actually accept their own generational groupings. Not surprisingly, Boomers are most apt to embrace their societal name – nearly three-fourths readily identify that way. But it’s downhill from there. Every progressively younger generation is less likely to associate themselves with their generational ID tags. In fact, fewer than four in ten so-called Gen Z’s are simpatico with being linked to that last letter in the alphabet. (After all, where do we go from here?)

Note that YouGov uses the Silent Generation as the label for those born before 1946. In Techsurvey, we did, too. That is, until many respondents (mostly in the public radio version of our study) complained. We have since “rebranded” them as members of the “Greatest” Generation (which other social scientists do as well), apparently mollifying the offended.

Still, only Boomers are generally copacetic with standard generational labeling, while virtually everyone else has bones to pick. According to Pinsker, Pew conducted a similar study back in 2015, only to find that many people “mis-identify” themselves. Their data showed that a third of Millennials think of themselves as Gen Xers, while 8% claim to be Baby Boomers.

Other mis-labelling occurs among the other generations, too. We might conclude that people are simply confused about where they actually fall generationally or this is their way of rejecting the idea of being pigeon-holed with one of these labels.

Other mis-labelling occurs among the other generations, too. We might conclude that people are simply confused about where they actually fall generationally or this is their way of rejecting the idea of being pigeon-holed with one of these labels.

Pinsker suggests the media own some of this problem because reporters and commentators love the stereotypes. They make it easy to categorize people, and worse, they help set up artificial generation friction, and even conflicts.

A Millennial friend of mine (not in radio, by the way) told me about an incident in her workplace, repopulating post-COVID. In what may be a preview of coming attractions when more of us return to the office (or station), she told me about how some of the Gen Z kids were screwing up the workplace by imposing their standards and mores on everyone else.

In fact, that was the topic of a recent New York Times piece by Emma Goldberg. Its title – in the “Business” section – says it all about generational tension:

“The 37 Year-Olds Are Afraid of the 23 Year-Olds Who Work For Them”

Her story suggests Gen Zs have become aggressive about imposing their ideas on standards on everyone else – from holidays (whether the company takes Juneteenth off) to pronoun assignments (he/him) to simply feeling unhip in the workplace.

This last point is nothing new. The younger generations have always enjoyed ridiculing their parents’ generation (remember, Boomers?). But Goldberg says the push from Gen Z is already changing the way many offices roll, and that in many cases, it has made the company culture more relaxed and casual.

But as The Atlantic’s Pinsker points out, the generational groupings aren’t just fraying, they often inaccurately create narratives that may lead to branding, marketing, and positioning mistakes. Even worse, people who otherwise would never stereotype by ethnicity or gender may be far more likely to label Millennials as “slackers,” Gen Xers as apathetic, and Boomers as out of it.

The moment we hear that about “my generation,” there is a tendency among many of us to push back – to explain “But I’m not that way.”

A number of years ago, Jacobs Media collaborated on an ethnographic research study with PRPD (the Public Radio Program Directors). Aptly for this post, we dubbed it “The Millennial Project.” We spent entire days following around twentysomethings – around the house, to and from work, in the workplace, and in the early evening hours.

Directors). Aptly for this post, we dubbed it “The Millennial Project.” We spent entire days following around twentysomethings – around the house, to and from work, in the workplace, and in the early evening hours.

It was an informative, even eye-opening study that helped inform public radio managers and programmers about the emerging audience and the challenges and opportunities they present. One of our questions for respondents asked whether they embrace the term “Millennial” to describe themselves.

And nearly across the board, they pointed out the label covers a lot of ground – and they did not consider themselves to be “typical Millennials.”

In fact, that identifier was often reserved for a younger sibling or co-worker, far more likely to typify the cultural stereotypes of the generation.

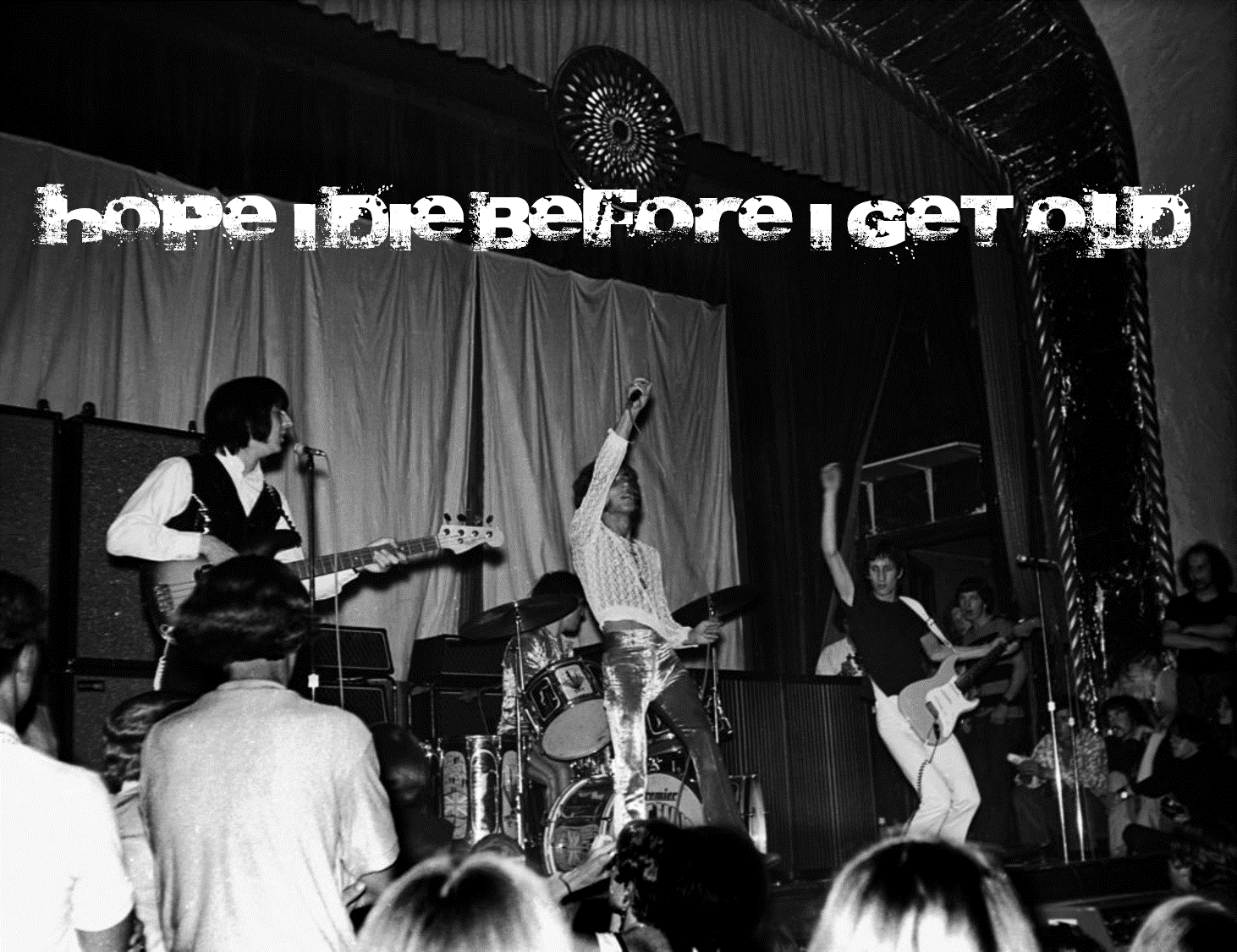

Ironically, the Who sang about this topic generations ago. In the stuttering “My Generation,” they offered up this wish:

“Hope I die before I get old.”

In the case of the faces of the band – Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey – it didn’t come true. They are both in their mid-seventies, still performing, and even occasionally sneering.

True to form, they are probably resistant to change, technophobic, and taking up jobs that would be better filled by younger musicians.

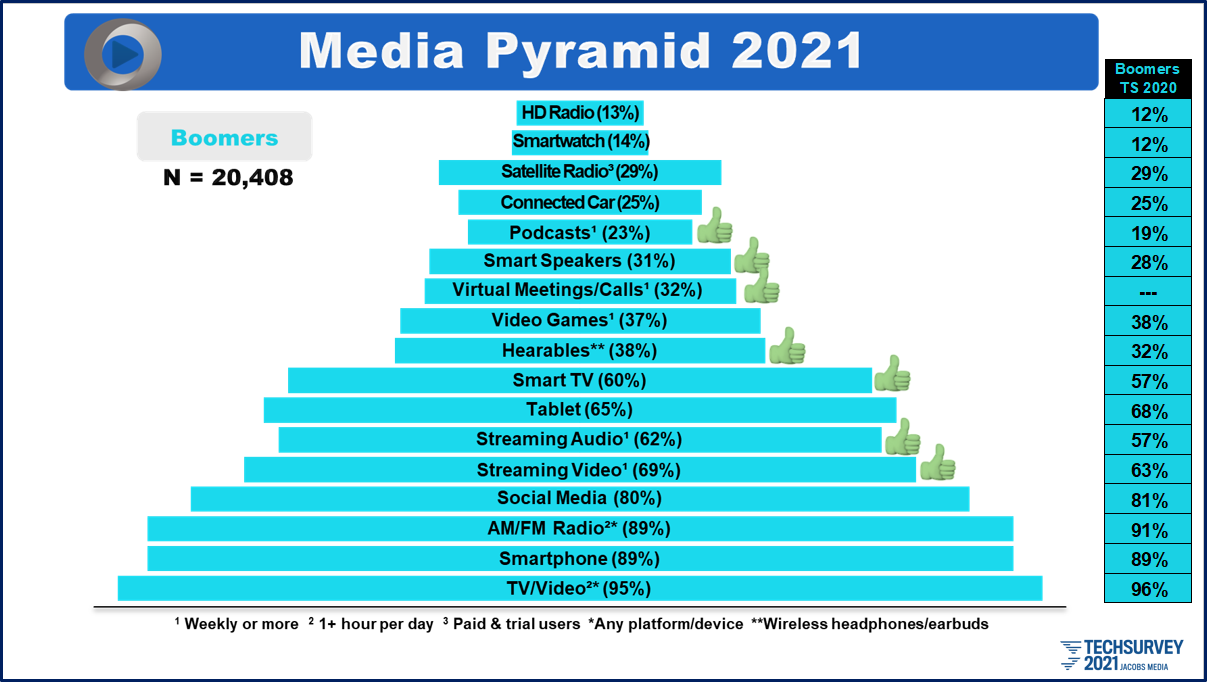

I talked about those Boomer stereotypes last June in a post called, “During COVID-19, Baby Boomers Played Catch-Up.” It featured our Media Usage Pyramid from this year’s Techsurvey, an eye-opener if you think of this generation as one that still can’t figure out how to text:

All those thumbs-up emojis symbolize media, gadgets, and activities that showed upward movement from the previous year’s study (the vertical bar at the far right). Streaming video and audio as well as listening to podcasts represent increased activity among Boomers. And their acquisition of gadgets that include smart TVs, “hearables,” and smart speakers are impressive as well.

The generational stereotypes only serve to further polarize an already great divided populace. More often than not, they add more friction, resentment, finger-pointing and conflict. And as social scientists increasingly are concluding, the generational delineations are based on imagining segmentation to begin with.

The generational stereotypes only serve to further polarize an already great divided populace. More often than not, they add more friction, resentment, finger-pointing and conflict. And as social scientists increasingly are concluding, the generational delineations are based on imagining segmentation to begin with.

As we look at other generations – and then we look in the mirror – we see things that run against the grain of these popular stereotypes. They erode our culture, or dialogue, and our discourse.

And Pete and Roger ended up being wrong. This getting older stuff ain’t so bad.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

I liked Bob Bellin’s comment that Classic Rock , “managed to become relevant to younger listeners, despite the age of its music.” While younger generations didn’t consume Classic Rock in their formative years, they seek it out today because of the quality. Sweet Emotion sounded great in the mid 70’s, it sounds great today and 30 years from now.

I had a feeling his comment would resonate for you, Scott. Classic Rock is truly a generational disruptor. You can leave your stereotypes at the door. Thanks for chiming in.

Digital vs. Analog

44.1 samples/sec. vs. smooth curve from the grooves.

“Generations” vs. gradual aging of human beings as the years pass.

See the pattern? It’s easier to pigeon-hole people than it is to analyze what’s actually happening, which is that from month to month, year by year, we individually learn about and adopt new things (technologies, music styles, memes, mannerisms, cliches)–or we don’t. Even that’s a false dichotomy, becase all of us pick up some new things and ignore others.

If we go for the new, is it because (a) we just like it, or (b) we’re young and diffident and crave group identity/acceptance? If we ignore the new, is it because (a) we’re mature enough to see a nonsensical fad with a short shelf-life, or (b) we’re just oblivious or too busy with more important stuff to pay attention? Or (as usual) somewhere in between?

You are right, Fred, that only the “boomer” label has even a shred of demographic substance. The rest is mental floss.

John, spot on. If it were only so simple to categorize entire groups of people. But it’s complicated, made even more so by the access to everything technology affords us. We’ve got much more work to do if we even hope to understand what makes mass audiences tick. Thanks for the comment.

I understand that marketers want to group the different age groups into clusters of people who have similar culture, tastes and likes to make their marketing, promotion and advertising campaigns more efficient, especially if they are about massive products and services.

I guess that’s where the idea of grouping people by ‘generations’ came from.

However, it is obvious that not all people of a generation fall into the stereotype. That is why we speak of ‘diversity’.

I am Colombian and I live in Mexico, and what strikes me most about this classification is that, if even in the United States they do not seem to agree with it, it seems wrong to me that in our emerging countries they want to adopt the definitions of those same generations, knowing that we are far behind in technology and we have cultures and customs very different from yours.

The baby Boom fenomena did not occur in all countries after World War II. An American gen-xer is not the same as an Argentine, Chilean or Honduran. He is not even equal to a British, Japanese or Australian one.

It’s just the copy-cat syndrome of our marketers who believe that using imported names and techniques makes them feel more sophisticated and trendy.

Tito, as one of those marketers, it is very much like taking the easy way out. There are more complexities about people than ever before, especially as the world becomes a smaller place. We need to work harder to improve our understanding of people – their needs, desires, and their media tastes. Thanks for commenting.

Well. Speaking from the platform of the lost generation known as the Brady Boomers (hat tip: Dan O’Day) I throw my hat in with those who take a psycho-graphic approach to programming. Most people in marketing are relatively young compared to the people who have the most buying power and influence that transcends the meme-ful and mostly empty messaging we see in most media; and the majority of marketing people just can’t get out of their own heads. There are always overarching values that tie communities together more effectively than mere demo/ethno-graphics. Example? Today’s election results. (Uh-oh. I hope I am not courting a flame war. I’m just making an observation.)

You’re right – in general, and the election results. Some issues span generational labels. Better put, they have nothing to do with when you were born, and everything to do with your experiences, your parents, and your mindset. Social scientists would be wise to not get trapped by the generational boundary lines. Good to hear from you, UL.

I think we get caught up in titles and other minutiae that in the end may not matter.

Radio folks, myself included tend to overthink things.

This came to me a few years back when my daughter’s playlist included The Beach Boys, Mel Torme (due to the Umbrella Academy), Pink, Aerosmith, Meghan Trainor, among others.

I got to thinking. “Back in my day” (like us old timers say), Stations played an unapologetic mix of music. The mentioned list is probably broad, but true radio guys know what I mean.

This all changed when we went from one or two stations to six or seven and we had to make up formats for them.

At the same time we toss out terms like Oldies because it was negative. But real listeners call anything older that year old an Oldies(even 90s songs).

It is interesting that radio is scared of some great songs because of their age. But, watch nearly any TV show, commercial or movie and these songs live.

Watch the British Thriller “last night in Soho” as an ex. The entire show is based on the music from another era and the very young stars and characters take the lead in championing the era in question.

In other words, someone likes that music and we don’t present it.

Just some thoughts from an a Gen Xer or , if you will, an Oldie but a goodie.

Brian, thanks for this – more perspective on a topic that can use some real-life observations. Thanks for weighing in.

I had lunch recently with a 50ish owner of a fairly large ad agency. The subject of generational differences in the workplace came up and he noted that if a meeting is scheduled for say, 2PM-3PM and at 3PM some agenda items hadn’t been discussed, most millennials will get up and leave precisely at 3. Millennials value their time in a different way than older generations do. For real.

Some friends of ours had made some surprisingly racist comments and we mentioned them in the presence of a 23 year old, who is generally quiet and not generally very outspoken. Shyness aside, their hackles were raised and they blurted out that if they had heard those comments in person they would have angrily confronted them about their racism. Gen Z takes social justice very seriously. My wife and I, conversely, while just as horrified by the comments, went along to get along and kept quiet. (I did feel compelled to point out the the FCC couldn’t and didn’t mandate the % of minorities in TV ads and that white people were not now required in all TV ads to, “act dumb” and no, I’m not making any of this up).

There really are discernable generational characteristics IMO and older marketers should ignore those very real differences at their own peril. I know that this goes against the well conceived premise of this column and agree its much nicer to think that we all are more nuanced than we’re given credit for. But I’m not sure that view is, in the aggregate, entirely accurate. Yes, dividing lines are arbitrary, but your own tech studies reveal that some very basic behaviors are very different when viewed through different generational lenses.

No points for frequent posting? Maybe so…how about an occasional shipment from Tiff’s Treats?

Bob, you’re right, of course, there are some traits that millions of people share, especially those born in the same time frame, experiencing the same things. Many citizens under the Gen Z umbrella have already lived through the Great Recession, COVID (and its many tentacles), and other cataclysmic events their predecessors have not. Still, they’re not the same.

I think back to my own experiences on the campus of the University of Michigan in the late 60’s/early 70’s. We were all protesting, we all had long hair, we all smoked weed, and we all listened to the Jefferson Airplane. Except we all didn’t. Many of my generational peers weren’t part of that college campus scene, they weren’t hippies, and they weren’t wearing bell bottoms and beads.

It cuts both ways. There are some generational similarities that are worth noting. And you’re right – the big, broad ones are picked up nicely in our Techsurveys. But when we OVER-generalize about generations, we may be leaving important findings on the research room floor.

Thanks for making these posts more interesting, Bob, with your comments.