The news that Amazon will be the next major player to start a new streaming radio service shouldn’t surprise us. While streaming for pure plays is essentially a business model that remains unprofitable, mega-tech firms like Google, Apple, and now Amazon can afford the losses because their other businesses – search, mobile gadgets, and retail – are so robust it really doesn’t matter if they lose money on streaming.

For Pandora and Spotify, however, it’s a very different story. Their entire model is predicated on streaming, and so they’re looking for the revenue mix that can lead to profitability – and eventually perhaps, dominance of the space.

It’s not easy, of course, because the revenue structure for pure plays is counter-intuitive. The more customers they attract, and the longer they use the service, the more that costs skyrocket. So success might come down to advertising revenue and how each pure play goes about it modeling it.

There are a lot of differences between Spotify and Pandora when it comes to their streaming structures, and the same can be said of the ways in which they are positioning their services to advertisers vis-à-vis radio.

The question is, are they predatory or complementary?

In Pandora’s case, clearly the former. They’ve been on the attack against radio almost from the beginning. Over the years, it’s easy to study their “body language” and the ways in which they position themselves as a better option than broadcast music stations.

Back in 2014, Pandora’s Chief Revenue Office, John Trimble, told Crain’s New York, “Half of the salespeople here are focused on broadcast radio.”

And just last week at the MIDEM conference, Pandora CEO Tim Westergren said this:

“Pandora is a radio product. It is replacing a medium – AM/FM radio, which does not compensate artists at all (in the U.S.).”

In an article in RAIN, Westergren boasted about having around 500 ad sales employees that he claims will “generate north of $600 million in revenue…more than the entire broadcast radio business pays.”

How’s that for drawing a line in the streaming sand?

Then there’s Spotify, the other pure play. And their approach to marketing Spotify Free (not the subscription service) has an entirely different tone. This was recently articulated by (former broadcaster) Les Hollander, Spotify’s Global Head of Audio Monetization. His rationale positions his service as complementary to broadcast radio.

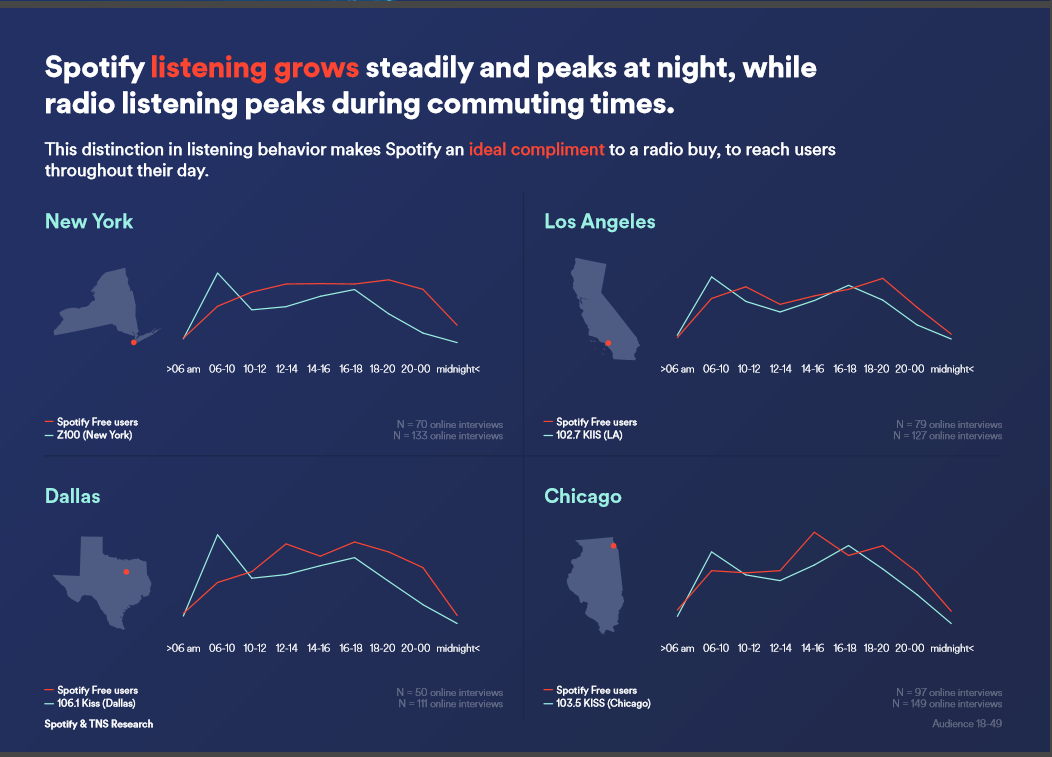

A new TNS study commissioned by Spotify points out areas where the pure play out-performs broadcast radio (holding attention/TSL, unique reach, and an audience more likely to travel or purchase items like new cars. But the pure play also takes a more complementary approach to radio, noting that each has its own unique strengths.

That takes the form of who Spotify reaches versus radio (Millennials versus Boomers), listening peaks (nights versus mornings), and location (the car versus lifestyle activities). As Hollander told RAIN, “Probably 20% of the 18-39 listeners you’re not reaching with the frequency you need just with broadcast. Then you have those listening moments that complement each other. Radio still has predominant ownership of the [car] dashboard. But in moments like studying, working out, doing housework, etc., streaming radio really owns those moments. For an advertiser, putting together all those moments is a critical component of the buy.”

Not exactly a humble brag, but modesty is never what sales is all about. And acknowledging broadcast radio’s strengths – while trumpeting Spotify’s unique attributes – makes a more rational and convincing case. This is in sharp contrast to Pandora’s more carnivorous approach. Marketers are left with the sense that the combination of broadcast radio and Spotify Free is the “secret sauce” to covering both the generations of consumers, and the times of day in which they’re engaged. You can see the daypart-by-daypart story below:

It makes you wonder how the radio vs. pure play war might have played out if Pandora hadn’t opted for its dog-eat-dog competitive attack strategy,

Like broadcasting, Internet streaming is a volatile, highly combative arena where profits are elusive, hope is eternal, and wild claims are always being made. And thinking about from the broadcast radio point of view, the medium’s simplicity, familiarity, reach, local connection, and ease of use continue to be strong arguments for strategically repositioning pure plays.

That is, if broadcasters were as aggressive and savvy as those trying so hard to disrupt it.

For radio, it is, indeed, the best and worst of times.

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

Amazon has been widely criticized for generating a lot of revenue and little or no profit. For better or worse, entering the streaming music space seems to fit that model perfectly.

So people love streamed music, buyers love advertising on it and no one can make a buck doing it – including the artists who will complain to whomever will Listen that they don’t get paid what they should from streaming.

Seriously…how is this going to end?

It’s clearly a crazy point in time. Everyone wants “in” the streaming music game despite its obvious downsides. Amazon obviously does not want this opportunity to go away. Remember they tried smartphones, too, and we saw ho that worked out.

I get and understand the attraction to being a pure play for entities like Google, Amazon, etc…if nothing else it serves as another way to be WITH and influencing your customer base.

As for the Pure plays? They are generating a huge amount of revenue even in relative infancy…I see them radically disrupting local radio and other industries.

Marty, the pure-plays have done a great job of building crime and exposure. The question is whether heir business models allow them to generate significant profit. Thanks for chiming in.