Five years ago, we launched a weekly feature in this blog – “Radio’s Most Innovative.” It ran for the better part of a year, highlighting some of the most amazing ideas, concepts, and accomplishments pulled off by radio pros.

We started the initiative because of the popular trope claiming there’s no innovation anymore in radio. While “RMI” honored some of the amazing accomplishments of the past, we mostly focused on innovations happening right now in and around the radio broadcasting industry.

We even came up with nifty trophies to commemorate our honorees. I see them on display in offices and credenzas throughout my travels.

We even came up with nifty trophies to commemorate our honorees. I see them on display in offices and credenzas throughout my travels.

We covered a lot of ground with RMI – the development of Selector and the first Christmas music station as well as saluting innovative people, such as Delilah, Art Vuolo, and Dave Ramsey. From new formats to breakthrough gadgets to different ways of doing this craft we call “radio,” we tried to shine a positive light on an industry often accused of not throwing the long ball since the days of consolidation were ushered in.

One of the things I learned from interviewing all these people is that most of the innovative ideas that went on to become wild successes were initially panned. Many sounded downright stupid.

Jeff Smulyan told the story about being mercilessly ragged on by his executive team when he brought up his idea of an all-sports station in New York. And you know that first PD who pitched changing formats to Christmas music in November and December was likely railed on by his researcher, consultant, and corporate chieftain.

I know what that felt like when I was trying to get Classic Rock off he ground in the early 1980’s. It was an idea that virtually no one in radio embraced. And the pushback from the trades, the record labels, and most rational people made me doubt the idea would work….at least for a while.

It takes courage to not just come up with an interesting concept, but to to see it all the way through to its fruition. But it’s those early stages where you learn quickly whether the idea has merit, and more importantly, whether you have the stones to stick with it in the face of criticism, skepticism, and all those people who warn you, “That will never work.”

Of course, there’s a funny side to innovation, especially if you look at it through the lens of Jerry Seinfeld. His hit show arguably became one of the top five best – and most successful – sitcoms of all time.

But it wasn’t like the other weekly network comedies that both preceded and followed “Seinfeld.” That’s because it was largely plotless – just a group of New York City singles looking at life through their weird perspective. Most of the “action” took place over coffee at Monk’s or in Jerry’s apartment.

It was “a show about nothing.”

And to remind us of its absurd uniqueness amidst all the carefully plotted network sitcoms and drama shows, Seinfeld sent up the pitch meeting at 30 Rock with the NBC network executives, as he and George (especially George) express their belief this seemingly idiotic concept will be a big hit.

This clip reminds us that most of the innovative ideas we now tacitly accept as brilliant conceived and perfectly executed almost all started out as lame and stupid, with someone in authority claiming, “That will never work.”

But you don’t get to innovation without experimentation, failure, and trying again.

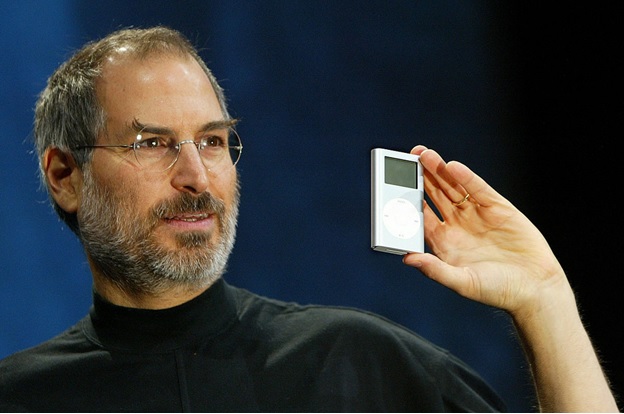

And all the research in the world isn’t always going to confirm you may actually be onto something. Consider this quote from Steve jobs as he examined his thinking leading into the creation of innovations like the iPod, iPhone, and other devices and gadgets we didn’t know we wanted:

“Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, a faster horse!’ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research.”

“Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, a faster horse!’ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research.”

Yet, we often rely on research to help us “pre-test” the success of a concept, a format, a bit, an idea without realizing consumers can only reliably give us feedback on something once it exists. And that takes stones of steel.

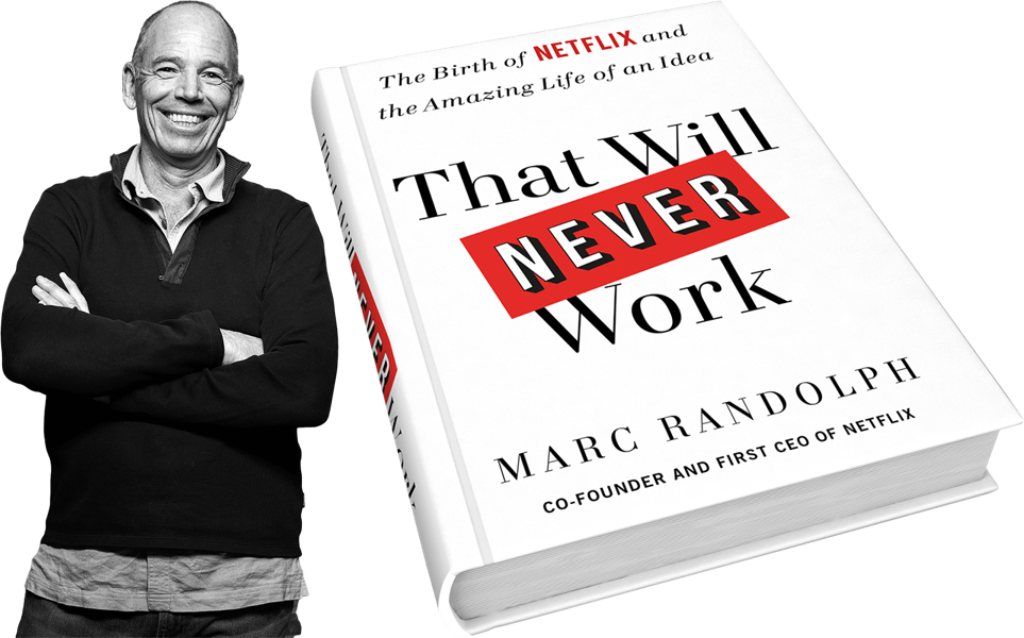

So, when I read Greg Satell‘s recent think piece in his “Digital Tonto” newsletter, I thought about what actually goes into innovation at the most basic level – especially when it comes to perseverance, while oftentimes ignoring those naysayers around you. Greg’s “The Truth Behind Netflix’s Incredible Success” takes a look at the wildly successful video streaming company, along with some of the brilliant decisions they’ve made.

He examines Netflix co-founder Marc Randolph‘s appropriately named new book, “That Will Never Work” (a phrase many of our radio innovators are very familiar  with). And one of the ongoing themes is how the self-effacing Randolph points to the phrase “Nobody knows anything” when explaining how Netflix actually took off.

with). And one of the ongoing themes is how the self-effacing Randolph points to the phrase “Nobody knows anything” when explaining how Netflix actually took off.

In fact, it’s a mantra, originally coined by author and screenwriter William Goldman (“The Princess Bride,” “Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid,” “Marathon Man”). All the research in the world cannot predict whether a movie (or TV show or radio format) will be accepted until it’s released. Despite the sophistication of consumer research and the integration of AI, there are still spectacular flops (the movie “Cats”) as well as total shockers that come out of nowhere to attain unbridled success (“Parasite”).

Randolph points to Netflix’s brilliant decision to switch from mailing DVDs in red envelopes to the video streaming subscription model that has vaulted Netflix to dominance. We all seemingly watch Netflix now, we can’t live without it, it’s redefined how we watch TV. Yadda, yadda, yadda, as Jerry Seinfeld might say.

Was Netflix actually a strategic master stroke? Hardly.

In fact, like many incredible innovations, Randolph writes about the “origin myth” that has attached itself to Netflix. You’ve probably heard it – or even repeated it – that co-founder Reed Hastings forgot about a movie he rented (probably from Blockbuster’s, right?) and ended up paying a $40 late fee. And thus, he was inspired to create a whole new model for enjoying films – tiered subscriptions and never any late fees.

But that’s not how it actually happened. The innovative, breakout, brilliant Netflix model was the product of tedious and frustrating trial and error. In fact, Randolph admits he couldn’t have possibly imagined how Netflix’s platform came to be. “I would have never come up with a monthly subscription service,” he admits.

“Nobody knows anything.”

As a consultant, I love the phrase, because after all the charts and graphs go away, we’re left with the sobering reality that until consumers experience something for themselves, we never know how a concept will be accepted – or rejected. And that’s very scary, which is one of the reasons why would-be innovators never surface their idea.

I thought about the existential truth of Goldman’s words this week. First, I had a chat with someone in the movie/TV industry, and we got into a conversation about Quibi – Jeffrey Katzenberg’s (Disney, DreamWorks) new mobile video subscription service featuring short 10 minute videos You may have seen it advertised during the Super Bowl, and in the weeks since.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N76DzOYxNyo

My friend immediately went into the “It’ll never work mode.” Sure, bite-sized, short-form videos may be popular and easy to consume while waiting in the dentist’s waiting room, but isn’t that what YouTube does – for free? And who wants to pay for yet another subscription service? Don’t we already have of these charges each month on our credit card statements? And besides, Quibi would have to somehow obtain video content written and directed by people like Stephen King or Quentin Tarantino before most people would ever consider subscribing.

Yeah, right. Of course, we won’t know whether Quibi is a home run or a goat until it’s launched in April. But as we saw with Disney+ late last year, Americans will shell out even more money for content if they think it’s worth it. And at small monthly fees, each of these services is no more expensive than a frous-frous coffee drink.

And then there is the return of flip-phones, first by Motorola (a reimagined Razr), followed by a new hinged entry by Samsung, the Galaxy Z Flip. Now, I defy you to even imagine a set of focus groups of iPhone owners sitting around talking about a revival of the flip-phone – and they’re loving this idea. Or that research survey, where consumers are asked whether they’ll ditch their traditional smartphones for a “new” model that is reminiscent of what we were using back to the 1990’s.

But that isn’t stopping Motorola and Samsung from trying it. And that led the New York Times’ Brian X. Chen to ask:

Foldable Phones Are Here. Do We Really Want Them?

To make the concept even dicier, unlike the flip-phones that some of us remember, these new models are well above the $1,000 mark, making their potential success an even bigger question.

Chen doesn’t really reach a conclusion, taking a “jury’s out” position. While a flip-phone offers more screen real estate by taking up less pocket space, he’s hard-pressed to think of other advantages to this OLED flexible screen technology.

And he quotes technology analyst Paolo Pescatore who opines that foldable phones are “a solution looking for a problem.” That’s about as close to “That will never work” as you can get.

This new TV spot below for the Samsung entrant ran in the Oscar’s this past Sunday night. Note most of the people in the commercial appear to be Gen Z’s, and perhaps that helps to explain the phone’s brand name – Z Flip:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WxbHs1QBs_4

So, while most of us “mature” smartphone owners look at these retro-looking flip-phones and scoff, it seems pretty clear they’re not aimed at us. They’re targeted to young consumers looking for something fresh, most of whom have never held a flip-phone in their hands.

Maybe in a phenomenon similar to young people exiting Facebook after seeing their parents and grandparents posting selfies and arguing about Trump on a platform that was once theirs, they could end up looking at their lookalike, traditional smartphones the same way. Every adult seemingly is carrying an iPhone. So, how can a teen stand out and make a statement with a phone that looks like something their mom carries around?

With a flip-phone, of course.

“Nobody knows anything.”

And that’s the case here, too. We’ll have to see whether these old/new flip-phones take off – especially among kids. And like many trends, that could spur a trend that travels to older generations – like texting, streaming, and podcasts.

Or maybe not.

Greg Satell’s “take” is a good one. The world is full of lousy ideas, but you have to work through a lot of them before you stumble onto success.

“Nobody knows anything.”

And that’s why companies have to commit to the not-so-pleasant tactic:

“Dare to do crap.”

That’s how you come up with something truly innovative.

Just don’t bring George Costanza with you to the pitch meeting.

You can check out Greg Satell’s writing here.

- How Will Radio Fare In The Battle For The Fourth Screen? - April 3, 2025

- Like A Pair Of Old Jeans - April 2, 2025

- What’s Fair Is Fair - April 1, 2025

Critical Questions:

Why do most programmers continue to program like it is still 1985 or worse, like it is 2005.

*we program to Neilsen in diary markets?? who does anything on paper?

*we still worry about 1/4 hours?

*instead of imbedding commercials (like Hulu does) once every 6 or 7 minutes playing one or two :30’s, we still do aggravating stop sets

*Less talk and more music? – aren’t Spotify, Pandora, iheart app, etc built for just that?

*programmers think time and temp is “local programming”???

I agree.

Excellent points.

Steve, you are correct these tactics are short-sighted and not at all innovative. But they define the radio conundrum – how do we fix – or rebuild – the plane when it’s flying at 35,000 feet? Radio executives are tasked with making their first quarter goals the old-fashioned way – getting good ratings and converting them to revenue. Problem is, those tactics do very little and probably hurts the industry in its competitive tangles with digital media players.

It is easy for someone like me to wave the “Let’s Innovate!” banner on the sidelines. And we’ve done our best with our own companies. But I have a tremendous amount of respect and even empathy for radio execs – and their staffs – who are trying to chew the digital gum and walk at the same time. Thanks for the comment.

I love this thinking so much. I wish every programmer… NO- every GM and EXEC would read this. That’s because other than college radio (or podcasts) Talent and Programming have been marginalized in their creativity for fear of point loss on media holdings on Wall Street. I believe radio can be brought back. It just needs some open space.

Excellent explanation. Fear is an innovation killer.

Karen, please see my response to Steve. Radio CAN be brought back. It is still a very powerful medium with amazing technology. It is simple, habitual, and everyone (over 18 at least) has used it. But the devil is in the details. GMs and Execs cannot just wave the wand and start throwing things at the wall. Most are understaffed, cash strapped, and struggling to hit their ratings and sales goals.

i have heard a number of analysts say that radio is under-capitalized, especially when you consider how much money many tech companies have burned through – and they’re still losing money. It’s a tough putt under good conditions. But much easier said that done. Thanks for reading the post & engaging.

Just went to Digital Tonto link and I’ll repete here my comment.

“Marc Andreesen stole his big idea for the browser from a developer in Switzerland so he’s not exactly a pioneer in my book.”

Doing Mornings at CBS’ 97.7 The Rocker, SF, we stole a slogan from some TV Exec for the show. “From now on whatever we do, even if it’s crap, we want it to be good crap!”

I think there’s an emoji for that! Thanks, Paul.

Imagine if your favorite football team was 10 points behind midway through the 4th quarter and their strategy for the game was to run out the clock. Welcome to commercial radio 2020.

Radio may or not be savable in the long run – it has squandered a lot of good opportunities over the years that the ship has pretty much sailed on. But it isn’t savable without some real intent – recognizing that different things need to be tried – that many of them will fail and a few could make a big difference, especially in the aggregate.

What’s really in the works? Another round of big mgmt/sales/support cuts are rumored for March at iHeart. They still probably have too much debt to prosper. Malone (Liberty Media) lets them twist in the wind for a couple of years, picks them up for half of their current valuation and creates a vertical for artists. He’ll own every layer in the process and will be able to control it all, without paying anything to anyone to promote any artist in his company.

How’s that for innovation?

It’s the kind of “innovation” the industry doesn’t need more of. Radio doesn’t save itself with the next wave of financial chicanery or working the loopholes. What’s needed is investment (a tough challenge in this environment) and the spirit of innovation discussed in the blog post. I was inspired by Marc Randolph’s words – humbling but true. But it’s all in the context of a rising media giant – Netflix – where profits have been elusive. I can think of a few radio CEOs that would welcome that yardstick. Thanks, Bob.