You attend enough conferences, and they often take on a certain theme or topic that runs through the many sessions, panels, keynotes, cocktail parties, and the exhibit hall. Back in the 90s, a number of these NAB gatherings were about acquisitions of assets – mostly stations and groups – especially as consolidation hit a high gear after the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was passed by Congress and signed by President Clinton. Oftentimes, companies timed their announcements and press releases to hit while the NAB was underway – a great way to not only be noticed but to dominate the conversation.

Over the last decade or so, some of these industry gatherings have taken on certain themes. One year, it was all about Jack-FM. Just a few years ago in 2018, the NAB that year was dominated by data – big data, first party data, you name it.

And while the NAB brass might have thought the organization’s 100th anniversary might have served as the umbrella for this year’s conference, it turned out to be something else:

AI

It wasn’t just the topic of the NAB; it dominated casual conversations in the hallways, bars, restaurants, and dinners. And unlike the cautious and even paranoid vibe I saw from many PDs and on-air types of the Country Radio Seminar last month in Nashville, the mood for AI at the NAB was somewhere between curious and enthusiastic.

I’ve talked about the sheer speed at which AI has reached critical mass in our country – and in the world. But for the radio industry, the applications have been obvious from Day One….or earlier. This technology is capable of handling many tasks that are common to radio and audio programming and content creation. From maximizing star talent to possibly replacing existing talent that’s been pedestrian in quality, the possibilities are endless.

For an industry that’s all but given up on nights, overnights, and weekends, the promise of AI is to make these dayparts – and days – sound personal and attended again. When radio sales managers decided they could no longer sell these time periods, the plug was pulled on staffing them with live talent. But the problem was that consumers were still tuning in during these unmanned dayparts, often wondering why radio had given up on itself during time periods when millions were listening.

Now thanks to this exciting new technology, many radio stations might regain a human touch, albeit “artificial.”

Pretty much everyone I bumped into at NAB embraced the philosophy that radio must accept this new technology and look for ways to make it work. That represents some level of progress, because in the past, a “wait and see” attitude toward new and now products, services, and innovations often was more common.

But unlike streaming, podcasts, and other technologies, AI is full of possibilities – saving money, saving time, and providing new levels of efficiency and scaling. I truly did not hear much in the way of concern about the industry shedding more talent. But to be fair, many voice concerns not only about the legality of AI applications, but also its social, moral, and ethical implications. All the same, many are forging ahead, while more and more companies are springing up, offering “solutions.”

It seems like with every passing week, the AI shit hits the fan. Last week, it was an artificially-created duet by Drake and The Weeknd that garnered tens of millions of views on TikTok, YouTube and Spotify before there was enough pushback to take “Heart On My Sleeve” down.

As the New York Times’ Joe Coscarelli noted, AI creations like this “may be a novelty for now. But the legal and creative questions it raises are here to stay.” “Heart On My Sleeve” used AI to clone the voice of both artists, while producing music similar enough to what they create to create an Internet sensation. Obviously, this has implications on the entire creative process.

Coscarelli quotes one of the million of fans who downloaded the song: “This is just the beginning.” And it is.

As I have posited before, Congress will probably get around to “doing something about” AI uses and abuses in 2030, based on how they’re just getting around to grappling with Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg.

And that brings us back to how radio might utilize AI in these early innings when new developments are seemingly taking place every day. So in the spirit of progress but also reason, let me remind you of how radio has fared in earlier decades when the latest and greatest innovations came to market. If past is prologue (and it is), radio’s track record with using new technologies is checkered at best, and actually erosive at worst.

Consider….

Music scheduling systems – Selector came to radio by RCS in 1979, thanks to the brilliance of Dr. Andy Economos. One of the first recipients of our “Radio’s’ Most Innovative” award, Andy talked to me about what a revolutionary tool Selector became. And in the early years, stations that embraced music scheduling on computer generally garnered better ratings. Before long, it became a ubiquitous, must-have tool for radio programmers.

But four decades later, do radio stations sound better? The ease of scheduling by computer has minimized a job that was once more an art form to a task. Those who take their time to meticulously schedule a day’s music often spend less time creating that next music “moment” – a special, feature, or unpredictable moment that makes their station stand out and be memorable. When everyone’s music is “perfect,” stations begin to sound the same, often utilizing many of the same rules and protocols.

But four decades later, do radio stations sound better? The ease of scheduling by computer has minimized a job that was once more an art form to a task. Those who take their time to meticulously schedule a day’s music often spend less time creating that next music “moment” – a special, feature, or unpredictable moment that makes their station stand out and be memorable. When everyone’s music is “perfect,” stations begin to sound the same, often utilizing many of the same rules and protocols.

And then there are the stations that don’t optimize their music scheduling software. These are the stations that slapdash together tomorrow’s log. The scheduling architecture itself may have been designed and built seven program directors ago,

The PPM methodology – When it debuted in U.S. radio in 2007, the technology was touted as elevating radio listening measurement by more accurately capturing real-time listening. And the hope was that stations would be better able to distinguish what was was working from what was not.

But 15 years later, you’d be hard-pressed to find too many programmers who believe radio has improved during the PPM era. In fact, it is more likely you’d find more observers who’d aver it has only made stations more bland, predictable, and safer.

But 15 years later, you’d be hard-pressed to find too many programmers who believe radio has improved during the PPM era. In fact, it is more likely you’d find more observers who’d aver it has only made stations more bland, predictable, and safer.

The shift to meters arguably has reduced playlists and personality talk time, while squeezing commercials into just two stopsets, often scheduled at the same time for most stations in PPM markets.

Rather than focus on what content that generates more quarter-hours (and listener satisfaction), the net-net of most stations in metered markets has been to play defense by eliminating errors and any hiccups that could interrupt the encoded signal.

Voicetracking – This one may be less cut-and-dried. Some personalities who prerecord shows are excellent at the task, making it nearly impossible to tell the difference. But for so many others, voicetracking has become an efficiency that distances talent from listeners, as well as the real-time happenings in a market or region.

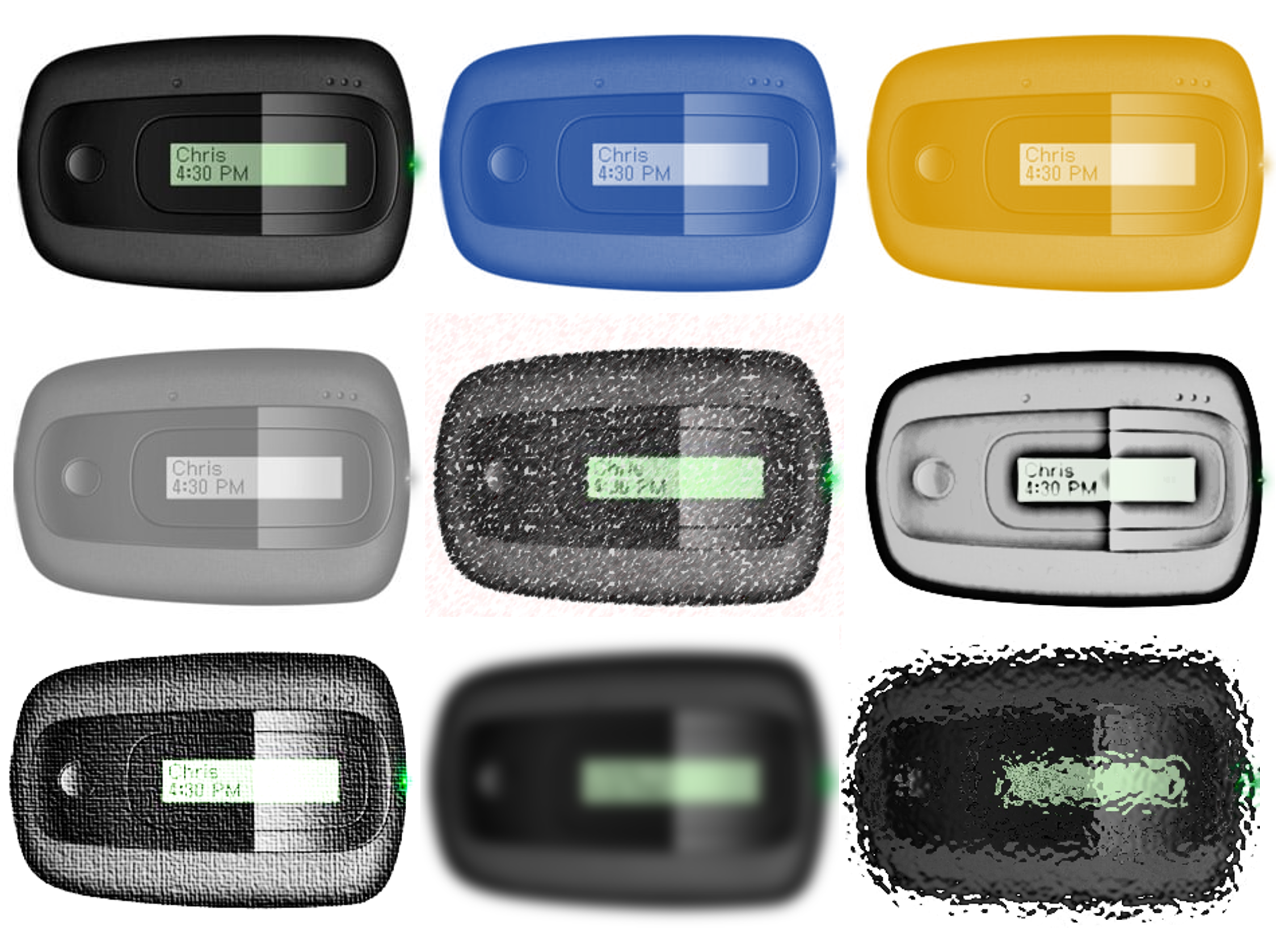

![]() Out of town voicetracking on the one hand has brought better talent into smaller markets or stations that couldn’t ordinarily afford quality personalities. To fill in a daypart or weekend shifts makes smart use of the technology. But when more shows are voicetracked than live, stations lose their balance. And when an entire building becomes automated for hours on end with no humans in the building, that’s when disaster can strike – a weather emergency, a celebrity death, a breaking news story that impacts the market or even a small town. After a while, consumers stop turning on the radio to find out what’s going on.

Out of town voicetracking on the one hand has brought better talent into smaller markets or stations that couldn’t ordinarily afford quality personalities. To fill in a daypart or weekend shifts makes smart use of the technology. But when more shows are voicetracked than live, stations lose their balance. And when an entire building becomes automated for hours on end with no humans in the building, that’s when disaster can strike – a weather emergency, a celebrity death, a breaking news story that impacts the market or even a small town. After a while, consumers stop turning on the radio to find out what’s going on.

Ultimately, an overdependence on voicetracking leaves a station vulnerable to falling out of touch with its community and audience. There are fewer ambassadors on staff to participate in the local events or in sales promotion that requires presence and experience.

These examples display a pattern of becoming so reliant on new technology and its requirements, a station can lose its sense of purpose, focus, and yes, even its humanity. The removal of mistakes – a key element these technologies promise and promote leads to a sound of sameness, predictability, and impersonality. It’s why radio sounds so similar to itself up and down the market dial or across the country.

And so, here comes AI for radio, a technology that offers efficiencies and perfection never imagined, in a package that appears to offer a level of creativity. At the NAB, convention-goers were treated to machine learning that could ensure perfect segues and transitions, the ability to access local information from news to weather, and the best voices imaginable for stations in markets of all sizes.

At some point – maybe sooner than later – the biggest personalities could license their voices to any radio station whether in Boston in Biloxi. Same with voice talent. Interestingly, radio has lost personalities and VO stars over the years who could be resurrected by AI. “American Top 40” could count down today’s hits, thanks to its ability to clone Casey Kasem‘s voice. Spooky? Cringeworthy? Tell that to the estates of Roy Orbison and Ronnie James Dio who have signed off on hologram concerts featuring their dear departed stars.

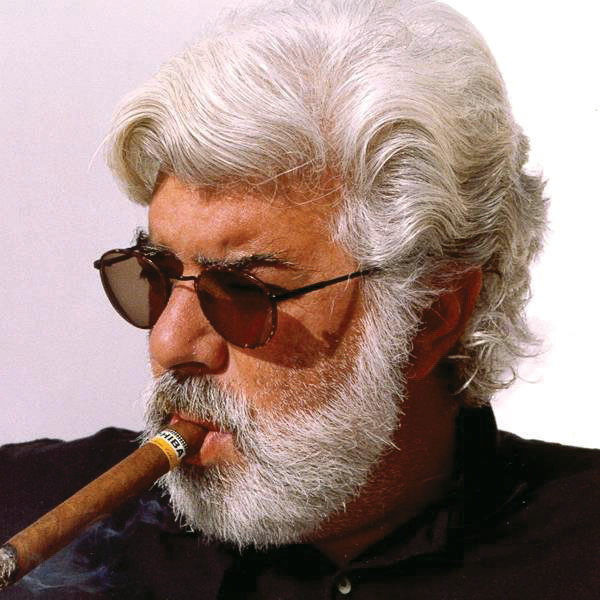

On a local radio station level, imagine the late Nick Michaels (pictured) doing positioners for your Classic Rock station thanks to AI technology. Of course, someone would have to write the brilliant copy that only Nick could craft. And while “reads” via AI will no doubt improve and become more natural, it is hard to imagine how a machine will be able to effectively mimic how Nick could turn a word or phrase by raising one of his bushy eyebrows and leaning into the mic.

that only Nick could craft. And while “reads” via AI will no doubt improve and become more natural, it is hard to imagine how a machine will be able to effectively mimic how Nick could turn a word or phrase by raising one of his bushy eyebrows and leaning into the mic.

In this scenario, how will agents be sure the copywriting by local staffs, reduced even further by economic pressures, will adequately craft language befitting of great talent? When anyone can license a voice, what controls will there be on what “he” or “she” actually reads?

In other words, what could go wrong? And for those of us who have watched technology get co-opted by budgetary pressures, this is a disaster movie we’ve seen before.

No one – and I mean no one – knows where AI technology will be headed in five years, or even five months. This will not be the last blog post about AI. Not even close. When the likes of Elon Musk asks for a six-month moratorium on its development, you know there may be danger around the next curve.

But at the NAB, there was a whole lotta puttin’ the pedal to the metal, hoping that AI could make for better sounding radio with even greater cost savings. But that’s the cautionary tale of technology, the likes of which have made for great dystopic films and stories where the machines take control and humanity pays a stiff price.

One of the other learnings of the aforementioned technological advancements is to keep an eye – and an ear – on the great stations and smart programmers who have skillfully made these technologies work for them, not for the bean counters. These are the stations that sparingly use new innovations to make their stations even better, without giving up anything in the process. Brands and their managers who realize why consumers and advertisers value what they do wisely keep their eye on the prize, letting the technology assist but never drive.

When you think about the three technologies discussed earlier in this post, AI might actually make them work better, leading to more effective use of their respective capabilities. Or maybe it will be used more to save money and reduce staff.

There’s no “art” in artificial intelligence. It will be up to radio broadcasters – programmers and creators – to find ways it can provide legit improvements to the medium. And in that spirit, ask yourself whether broadcast radio in America sounds better since these technologies were rolled out? Do radio stations today do a better job of serving their various constituencies since the advent of these techie advancements? I know from experience the answers to these questions will vary widely. Beauty – and great radio – are in the eye and ear of the beholder.

There’s no “art” in artificial intelligence. It will be up to radio broadcasters – programmers and creators – to find ways it can provide legit improvements to the medium. And in that spirit, ask yourself whether broadcast radio in America sounds better since these technologies were rolled out? Do radio stations today do a better job of serving their various constituencies since the advent of these techie advancements? I know from experience the answers to these questions will vary widely. Beauty – and great radio – are in the eye and ear of the beholder.

But hopefully we can learn something from our past dalliances with new innovations. How will we be able to use AI to enhance the medium and station brands? Can it allow radio to actually improve its service to audiences, advertisers, and communities? Where will it make stations sound better? And how might it degrade its quality?

At the BMI dinner at NAB, I spent time with radio elder statesman, Jerry Lee, and I brought up the AI topic. Without hesitation, Jerry expressed excitement for its potential, reminding me of the importance of broadcasters learning everything they can about this technology, what it can do, and where it can be accretive to how radio sounds today.

And over the weekend, I read this quote from recording star, Seal. Like so many in the music industry, he is down the path of test-driving AI advancements, specifically ChatGPT. And while there will be more attention on the Drake/The Weeknd “collaboration,” Seal’s quote is both thoughtful and realistic:

And then this, perhaps a look into radio’s more immediate future from “60 Minutes'” Scott Pelley. Will we all be making these types of announcements before and after shows?

@60minutes This message is a first for 60 Minutes: “We’ll end with a note that has never appeared on 60 Minutes, but one, in the AI revolution, you may be hearing often: the preceding was created with 100% human content.” #ai #artificialintelligence #60minutes #news ♬ original sound – 60 Minutes

And to that I’ll add:

Today’s blog post was written and published with 100% human content. I thought you’d want to know.

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

I’m guessing for now, A.I. might come to the rescue of stations with fairly interchangeable talents — just like in the past when stations would lose a “Johnny Daniels” and put in a new guy reusing the same name, not missing a beat.

But creating high-profile jocks? We may still be a ways away from that. Its not hard to envision the *tonality* of a synthetically-generated jock coming close to emulating most well-known high profile talent, but at the moment, I’m comparing A.I. Radio to self-driving cars: great idea on paper, but someone’s gonna get hurt the moment we look away.

“We have met the enemy, and he is us.” ~ Pogo

Now that we’ve fixed the content with AI, can we fix the air processing with AI as well? Far too many stations sound like hammered dog $h*t because nobody knows how to set up a processor anymore.

Fred, I received an interesting piece of feedback this weekend from a P-1. She proclaimed her undying love for our station, gave her suggestion on something we might do better in the future, and then closed her email with a sentence that I will never forget:

“Whatever you do, don’t let the robots take over The Drive. Please.”

I’ve always been a big fan of science fiction, and would suggest we’d all do well to read and study Isaac Asimov’s “I Robot.” (skip the movie, they miss a lot in the screenplay).

The biggest difference to date between Asimov’s eerie vision of the future (written mostly in the 1940s, if you can believe it…) is that the author’s “Three Laws of Robotics” are largely ignored in most of the recent innovations that are grabbing headlines and causing concern. For the unfamiliar, the “three laws” are:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The choices to obey and/or manipulate these three articles makes for a fascinating collection of literature.

Later on, Asimov added a “Zeroth Law” that states a robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm. When asked if humans would follow the laws, he stated “I have my answer ready whenever someone asks me if I think that my Three Laws of Robotics will actually be used to govern the behavior of robots, once they become versatile and flexible enough to be able to choose among different courses of behavior. My answer is yes, the Three Laws are the only way in which rational human beings can deal with robots—or with anything else. But when I say that, I always remember (sadly) that human beings are not always rational.”

It’s hard to argue with him.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Laws_of_Robotics)

“I Robot” was one of the first books I read when my sci-fi interest began as a teen. You remember it better than me. But I do recall loving those short stories, connected by those “three laws.’ Brilliant stuff, and worth picking up again in light of what’s happening right now. Thanks, Keith.

Hi, Fred.

You say that “radio’s track record with using new technologies is checkered at best, and actually erosive at worst”, and you mention technologies like Music scheduling systems, the PPM methodology and Voicetracking, but you fail to mention a very important one: Audio automation systems.

They took a lot of work off the operators, especially the radio DJs, who no longer had to take the records out of their covers, clean them, put the needle in the right place, cue them, and when finished return them to their covers and stack them.

And not to mention the commercials: the use of countless cartridges was no longer necessary. In addition, you could get the broadcast report of the commercials: at what time did they sound, how many times a day and if there were any omissions.

These computerized automation systems made it easier for DJs, who now supposedly could have a lot more time to prepare what they’re going to say when they open the microphone, but it also took away that adrenaline, that excitement, that sense of being in charge of a spaceship at the time of operating all the equipment that allowed an on-air transmission, making now the on-air shifts more monotonous, routine and boring.

On the other hand, you mention voice cloning, and I think it would be worth delving into that subject, since it could take many people’s jobs away. Thanks to new technologies, it is now possible for anyone, without having trained to be a voice actor, to become a voice-over for commercials, documentaries, videos, presentations, and even voice dubbing.

I even read somewhere that in the near future, instead of using local voices to dub film or TV artists into other languages, their voices could be cloned to do their own dubbing into Chinese, French, German, Italian, Spanish or any language, including the possibility of doing the lip-synch automatically.

This is really worrying for this guild.

I agree that we must be aware of all the new trends, but it is also key to ask ourselves what benefit we can get from them and also what threats they can bring us.

We’re in basic agreement, Tito. There’s a tendency to embrace new tech – or reject it – often with little forethought. Every technology I talked about today was initially designed as a time saver or to improve upon existing procedures. As you suggest at the end, it’s important to step back and do a long think about the pros and cons of new innovations – before we install them at our stations.

Tito makes a number of points I’ve also thought about–that the more technology “does” for us, the more we “lose” something in the process, if nothing more than that sense of controlling that “spaceship.” (GREAT analogy, Tito!) And I would add one more to the list. I might be the only person in your readership that feels this way but I think losing the requirement for an FCC license hurt the industry as well. I mean, come on, it wasn’t THAT difficult of a test–and it showed at least SOME commitment and interest to radio. At the risk of sounding like “cranky old-timer guy,” I think radio really did suffer for the loss of people willing to put in at least that much effort to enter the industry. Old man rant, over.