We all know the consumer’s attention span is shrinking because we have our own personal experience to draw from. Everything’s getting shorter, to the point, and truncated (except baseball games), and that’s part of the reason why platforms like Twitter, Snapchat, and Vine have caught on in a big way.

Tweets and snaps require very little time or a whole lot of thought when they come flashing by. They capture our attention in the moment – or they don’t. In Twitter’s case, most tweets come with a link. If the short message or come-on connects for you, you click to read an article, a picture, or some web element.

This minimalist trend is also why the “PPM Rules” have become synonymous with communicating content in shorter bursts. Sadly, the ratings pressure and interpretation of the methodology has been translated to “talk less” when in fact, it might be better to say “engage quicker.”

This minimalist trend is also why the “PPM Rules” have become synonymous with communicating content in shorter bursts. Sadly, the ratings pressure and interpretation of the methodology has been translated to “talk less” when in fact, it might be better to say “engage quicker.”

That means saying more but delivering it in a smaller envelope, a skill that the first generation of Top 40 jocks perfected back in the ‘60s. You had to be compelling and fun over the first few seconds of Del Shannon’s “Runaway” in order to connect with fans in those days. The idea was to keep it moving, but get your content across in a staccato but highly entertaining way.

Now Gord Hotchkiss of MediaPost’s “Search Insider” has written a piece called “So Six Seconds Is The Secret, Huh?” that supports this theory. The essence of it is that because consumers are moving so quickly, “we have to somehow jam our messages into tiny little cracks.”

And it’s interesting that Vines are, in fact, that exact length. As Vine co-founder Dom Hoffmann jokingly told NPR last year about how they chose that particular span of time, “One day we did wake up and say, six seconds.” But the truth is that after experimenting with various lengths, their team concluded that while 9 or 10 seconds was too long, 5 seemed too brief. Thus, the 6 second solution. And as NPR reported, it “allowed for the aesthetic feel the creators wanted but preserved the quickness they wanted to promise users.” Sounds like something Bill Drake might have said.

Similar to some of Lori Lewis’ think pieces about being in the moment with real-time social media interaction, Hotchkiss points to Oreo’s deft tweet about the blackout in the 2013 Super Bowl game, while Lori talks about Arby’s quickie moment of millinery fame, using a tweet to joke about Pharrell Williams’ chapeau in this year’s Grammy’s broadcast.

And that brings me to an email exchange I had the other day with a broadcasting sales maven – a person who has a strong understanding of the power of commercial messaging. We got onto the topic of “blinks” – those quick, just-a-few-seconds-long mentions (or “shout-outs”) that Clear Channel made famous a few years back.

They seem to have fallen by the wayside and they are certainly not a major sales emphasis, but you have to wonder if perhaps they were retired too early. WBEB’s Jerry Lee talks about how the quality of radio advertising needs massive improvement, but perhaps part of the issue really has to do with spot and stopset length. Radio has sadly developed a nasty paradigm – a series of seemingly endless :30 commercials in two long clusters an hour. It’s so bad that just about everyone does it.

In this fast-paced media environment, is it really possible for any of this advertising to be recalled or processed in a meaningful or memorable way by consumers? And when everyone’s essentially executing their commercial policy exactly the same way, is this model truly working for radio either?

It reminded me of some Listener Advisory Board groups I conducted a few years ago in a market where “blinks” had become somewhat commonplace. It didn’t take long before the discussion with this conference room full of listeners gravitated to the always fun topic of “too many commercials on the radio.”

And in the middle of this bitch fest, one of the respondents mentioned having heard these little mini-bites that we know as “blinks.” And from there, several others chimed in and started recalling specific advertisers by name who used these staccato clips to gain brand awareness and attention. These listeners actually found these “blinks” to be curious, different, obviously memorable and attention-getting, and almost fun.

I remember thinking at the time that perhaps the “blink” model was more effective than many thought. We certainly never see that kind of recall – and even enthusiasm – for conventional :30s and :60. And in the harsh light of long bunches of commercials in a row, is radio effectively marketing goods and services to its diverse clientele? Or is it repelling them, and encouraging them to go elsewhere?

No one reading this post can really answer that question because no one (that I’m aware of) has actually make a serious attempt to experiment with a different model. That is, drastically cutting the spotload, replacing the existing architecture with much shorter (and perhaps) even more frequent messages, and other maneuvers that might differentiate a station, make it more palatable to fickle consumers, and even help advertisers achieve their goals. While Hotchkiss talks about the six second length, we clearly see brands like Pandora in the :10-:15 range- a length that is more compatible with a consumer’s level of patience and tolerance.

Clearly, the two-long-stopset cluster architecture has some degree of effectiveness in PPM – except when 20 stations in the market all employ the “bowtie” stopsets. When listeners complain that everyone in the market plays commercials at the same time, it’s not just a feeling. It’s often true.

And it all breaks down when you look at music radio through the digital media lens where spotload truly matters and stopset placement is irrelevant. What is the experience for the consumer, especially compared to other platforms and services that offer the same (if not better playlists) with minimal or no commercials at all? That’s the new competitive arena facing broadcast radio, and there has to be a bona fide value proposition for the consumer.

Or new commercial architecture and execution that provides a better, more enjoyable alternative.

Even consumers know that advertisements are the price you pay for broadcast commercial radio. They are part of the grand bargain. But that model worked in an environment of scarcity where the only thing you could listen to in your car was AM/FM radio or a cassette or CD.

In a world of plenty, it’s a no bargain. Maybe public radio has the right answer. It has some similarity to the satellite radio model with one key exception: it’s subscription radio with the honor system. Consumers don’t have to pay to listen to NPR or your local public radio station. But the content is so compelling, unique, and different that many of them actually do.

But the “commercial environment” – what public radio operators call “underwriting” – is limited, clean, fast, and painless. In fact, many public radio listeners will tell you they personally have something in common with the businesses, foundations, and brands that pay for underwriting messages – they both appreciate and support public radio programming. How’s that for connecting with listeners and advertisers?

Great brands exude trust and credibility. That’s something that public radio has all over its commercial radio counterparts.

But commercial radio operators have a weapon of their own – extra stations that are not contributing to the programming strategy or revenue base of the cluster in any meaningful way. In every market in the country, those FM stations sitting at the bottom 20% are the also-rans, dogs, and failures that every significant broadcaster owns but few want to talk about. In many clusters, they only serve a “value added” purpose and bring little, if anything, to the good of the group.

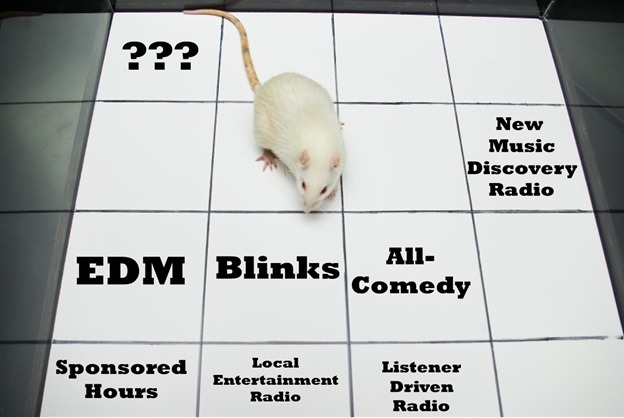

But these same stations could serve a higher purpose. They could be turned into the lab rats, the guinea pigs, the sandboxes, and the pilot projects where commercial architecture and programming experimentation could be taking place.

An all-comedy station, an EDM station, a local entertainment and events station, storyteller radio – all of these good, bad, and crazy ideas could be leveraged in initiatives to actually create something different, grow a potential new franchise, and generate some much-needed buzz for radio.

For both programming and commercial strategies, it’s time to deploy some of these stagnant stations into exciting adventures and lab experiments in learning, improving, and surviving.

Which corporate king is willing to step up and truly try something new, brash, and experimental in 2014 with that third Country or fourth Rock station in one of their markets?

By the way, the talk-up time on “Runaway?” Yup, six seconds.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Fred, what a great idea. Lord knows there are clusters where the 5th+ station is little more than a simulcast or “boxed” music machine. At least some of that inventory could be experimented with. A few 6- second spots in each break. How fast would that get us back to music? A station could try it in drive times to start with. Very interesting.

Thanks, Jack, and maybe I’m naïve, but I’m thinking that even Wall St. might be impressed with some “lab experiments” with the goal of finding new formats, discovering new talent, and providing a proving ground for our more successful stations. Appreciate you taking the time to comment.

The obvious example of this “lab experiment” would have to be the FM rock format of the late ’60s/’early 70s (WNEW/WMMR or my local favorite WBUS). Here was this new FM thing and no one knew what the hell to do with it. About the only thing anyone could figure out was beautiful music with automation (god, those things could take off a finger if you weren’t careful) ’cause this FM thing sure wasn’t making any money (In the words of “Inside Llewyn Davis” Bud Grossman ‘I don’t hear any money’) . Until those pesky kids convinced station owners to let them have a shot with that wacky music kids were listening to, but couldn’t get on the radio. Those wacky kids didn’t create a format, they created a community (are you listening Facebook?), a happening. It’s all happening at the KZEW.

Interesting things can happen when there’s no money on the line, and of course, that’s pretty much the case with “dog” FM stations, and certainly HD2 stations (which too often, try to mimic their HD1 siblings). As I mentioned in an earlier comment, CEOs are masterful at spinning their quarterly results, their big initiatives, and what’s happening in various markets. Isn’t it logical that some smart experimentation would be accepted by broadcasters trying to do new things, to serve new audiences, to break out of the format ruts and try something different? Thanks for the perspective and the encouragement, John.