One thing is for sure. Forget about your politics and how you voted (you did vote, didn’t you?), most of us agree that what we’re living through now is off the charts. If you’ve studied your history, you know there have been trying times in past eras, but it sure feels different this time.

Just 90 or so years ago, the Great Depression, World War II, the Holocaust, and the deployment of nuclear weapons impacted the years in which many of our parents or grandparents lived. Later, it was the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and MLK, the Vietnam War, Watergate, and other tragedies that marked the 60’s and 70’s, the period in which I came of age. While that period gave us some truly seminal music, the price was very, very high.

Enter today – now. Over the past 20 or so years, our lives have been scarred – by 9/11, the Great Recession, political turmoil, and of course the coronavirus, COVID-19.

And while the virus has clearly abated, and most of us are back to our “normal” routines, we’ve been deeply impacted by these experiences. It seems like one disaster piled atop the other in a sort of perpetual motion of doom and gloom. We seem to leap from crisis to crisis, whether it’s climate change, the Ukraine/Russia War, the culture wars, and deep societal divisions that impact our holiday gatherings.

Is it the media – and social media – fueling the angst and panic? Or is it really different this time?

This phenomenon – a circuit of bad news – has a name.

Polycrisis

The father of this unfortunate phenomenon is Adam Tooze (pictured) a historian who studies what The Atlantic‘s Annie Lowrey refers to as “economic disasters.”

a historian who studies what The Atlantic‘s Annie Lowrey refers to as “economic disasters.”

As Tooze explains in the article, “the whole is ever more dangerous than the sum of the parts.” He has become something of a multimedia star, writing articles, books, and of course, a podcast cleverly named “Ones & Tooze.”

Writer Derek Thompson says the current mentality of crises that pile on one another goes a long way toward explaining how we’re feeling. He offers up a theory for what’s going on now. He relates it to the German concept of “weltschmerz” – which translates to world sadness, due in no small part to the impending doom of the news cycle.

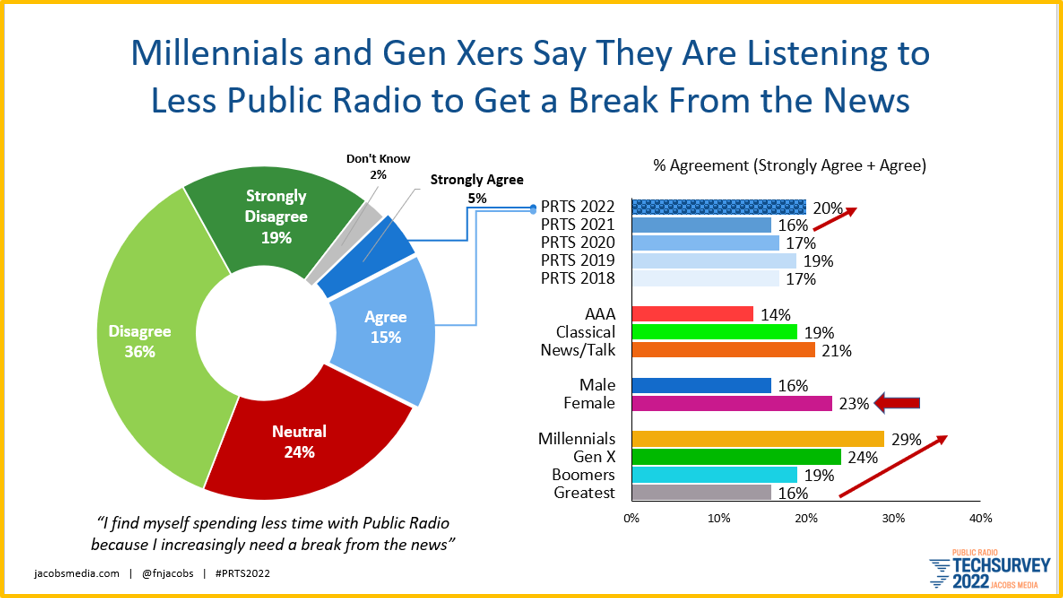

We have seen this phenomenon the last couple of years in our Public Radio Techsurveys. Those who normally describe themselves as “news junkies” are showing a growing tendency to seek escape from the cycle that incessantly plays out on public radio and cable news

Thompson calls this “mediaschmerz,” and you can see its effects in the chart below:

Younger citizens, women, and fans of NPR News stations are even more likely to be repelled by coverage of our polycrisis, a trend that reached a new high in this year’s survey.

So, what about radio?

I would offer up my term for the confluence of crises – “radioschmerz” – because the travails of the industry aren’t just limited to a calamity or two – it’s lots of stuff, seemingly occurring one after the other, and it has metastasized.

Think about it….a host of major issues and threats have reared their ugly heads in just the last couple decades. Among them:

- The consolidation and Wall Street wave that coincided with the explosion of the Internet and streaming. While arguable, it could be concluded that fewer and bigger companies did little to spur content innovation.

- The invention of the iPod, changing the way we listen to, buy, and collect music. The result was the commoditization of the music.

- The streaming explosion, playlists, and smartphones all leading to infinite choice, ending radio’s role as audio gatekeeper. All the songs in the world fit on your iPhone.

- The expansion of other audio products, including satellite radio and podcasts. Each also brought about an exit of radio talent, such as Howard Stern and many public radio stars.

- Rather than competing against other owners of other radio properties, broadcasters now compete in some form or fashion with the biggest, smartest, and richest tech/media companies on the planet, including Apple, Amazon, Spotify, and Facebook.

- The impact of all this choice, along with smartphone connectivity in the car dashboard – radio’s #1 listening location – coupled with the advent of hi-tech infotainment systems, has resulted in the medium becoming another choice on four wheels.

- Radio’s focus on adult demos to capture the most ad dollars, has resulted in broadcasters eschewing the Baby Boom nostalgia movement on the one hand, while ignoring Gen Z on the other, leading to generations who are not engaged by or listen to broadcast radio.

- The transformation to metered-measured ratings, leading to more conservative programming at a time when content outside of radio was exploding.

- The ravages of economic meltdowns on the radio economy, starting with the Great Recession, continuing through the pandemic, are alive and not-so-well today with the ongoing recession fears. Less budget for staff, research, marketing, promotion – investment.

- The COVID pandemic, producing precious little commuting in 2020, and a WFH mindset that continues to this day. The minimization of morning and afternoon drive radio is a result of people driving less often and less routinely.

I’m sure there’s more.

But isn’t this enough to tell us radio’s problems aren’t simple, singular, nor are they linear. They are complicated, intertwined, and existential. There is no smoking gun. There’s a whole army. And it is bigger than any of us, and any of the industry’s largest companies.

In much the same way we must cope with the polycrisis in our world, in our country, and perhaps in the region where we live and work, we are compelled to face up to the challenges in our careers and work lives.

In much the same way we must cope with the polycrisis in our world, in our country, and perhaps in the region where we live and work, we are compelled to face up to the challenges in our careers and work lives.

A well-written blog from earlier this year might provide some clues. You’ll like the title:

“How to navigate a world of polycrisis”

As the authors point out, our brains are not configured to multitask, despite how we watch football, text, and barbeque chicken at the same time. Because the effects we feel from cascading crises are both bigger than us and interconnected, we feel overwhelmed when trying to address multiple calamities at the same time.

But perhaps crises are more predictable than we think. But when our first reaction to bad news is denial, we set ourselves up for disaster. Whether it was the tsunami of the Internet and streaming, or the tragedy that was COVID, you could see them coming.

set ourselves up for disaster. Whether it was the tsunami of the Internet and streaming, or the tragedy that was COVID, you could see them coming.

In fact from the pandemic, we have, in fact, learned coping skills, including my favorite:

“Control the controllables”

The authors call it “fixing what we can control.” And eating that elephant one bite at a time is the only choice we have. They suggest we can learn from past disasters as banks survived COVID largely because of lessons learned from the 2008 economic meltdown.

They also make the point that “incomplete projects” (from the past) can make a comeback; that the hard work from years ago – unapplied – can be dusted off and revamped to suit today’s needs.

And then there’s their answer to the polycrisis that has alluded radio for decades:

“The motto ‘Together we are stronger’ is true”

Or “speak in one voice” which we’ve seen play out with NATO in the Ukraine/Russia War or in the EU with the pandemic.

As the authors of the polycrisis blog remind us, “Extraordinary situations call for extraordinary measures.”

That sounds like an imperative for the radio broadcasting industry in the U.S.

Finally, three keywords:

Empathy, adaptability, and resilience

We’ve been tested over the last three years, but I would argue we’ve had more than two decades of undeniable stress.

We’ve been tested over the last three years, but I would argue we’ve had more than two decades of undeniable stress.

We’re still standing, in spite of it all.

Many analysts agree the domino effect of one crisis after another isn’t going away, that we’re fated to feel like Indiana Jones fending off attacker after attacker.

These skills we’ve developed will help get us through whatever’s coming next.

Looking down the road to see around those corners is an important part of our survival instincts. That’s why CES has to be on Jacobs Media’s agenda for early 2023.

Stay tuned.

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

Stay connected, versatile and keep the ball rolling. Thank you, Sir Fred.

I’m one of those “news junkies” feeling the burn, Fred. Though I am not tuning away from my NPR stations because of it, I find that I’ve adopted a kind of triage listening for what I pay close attention to:

– matters of public interest that are being productively addressed by people situated to do so;

– matters of public interest that aren’t being productively addressed and no one seems to know what to do; and

– matters of public interest that are being addressed by measures that I might accelerate through my own initiative/attention.

Only that third category, slender though it may be, gets my undivided attention. It’s also the only way to preserve some semblence of sanity.

Self-preservation, John. I get it. It’s hard to be a thinking human being and not want to scream sometimes because of the onslaught of disheartening news. And journalists have no choice but to keep covering it. It’s hard note to feel a sense of hopeless. Hoping this too shall pass.