At Jacobs Media, we have long been proponents of giving fans a voice in how our stations sound. Strategically, this provides the opportunity to posture changes as the audience suggested, as in “You told us you wanted….so starting Monday….” This can be a great tactic, especially on the heels of a research study where these moves are clearly obvious ones to everyone in the room.

But predicating an entire company – or an industry, for that matter – on the suggestions from consumers is a whole other thing.  Interestingly, it has happened – not that long ago and to a brand you know and very likely subscribe to:

Interestingly, it has happened – not that long ago and to a brand you know and very likely subscribe to:

Netflix

Back in 2006 when the brand was all about mailing DVDs to us in those familiar red envelopes, Netflix used software called Cinematch to recommend movies we might like. CEO Reed Hastings’ idea was to improve its efficiency which, like extending time-spent listening in radio, could have been a game-changer for Netflix.

To tap into the brilliance of Netflix users and more to the point, code writers everywhere, the company hatched the “Netflix Prize,” a one million dollar reward that attracted 30,000 competitors to take a shot at improving the company’s recommendation engine.

A detailed story in Thrillist by Dan Jackson explores this innovative competition, nearly won by a computer nerd named Lester Mackey who headed up a team originally called Dinosaur Planet, later consolidating into a “mega-team” known as The Ensemble.

The contest became complicated as well as legendary in software circles, inspiring a “Great Race” competition that ended in a tie – eventually won by a team led by AT&T nerds.

As it turned out, Netflix did not end up using the solution that came out of “Prize,” but Jackson reports the competition advanced how AI is used in recommendation engines across the spectrum.

By the time “Netflix Prize” came to its conclusion, the company had moved onto the launch of its streaming video platform in early 2007, the start of the system in use today. Thanks to the data provided by streaming, Jackson explains, the Netflix model “became less about how you rate media and more about what you actually consume.”

In other words, our actual behavior – the videos we stream.

In other words, our actual behavior – the videos we stream.

And today, it has led to how AI is being widely used to recommend the series and shows we end up watching – and bingeing.

But the Netflix concept of dangling a reward in front of able and enthusiastic competitors garnered a lot of attention.

It is not a new idea.

In fact, Nieman Lab‘s Julia Barton, tells us the radio broadcasting industry had the same idea.

The difference is that it was 100 years ago, and the prize? A hefty $500.

Still, the contest turned out to be successful. Just as Netflix turned to consumers early on in the company’s development, so did pioneer radio broadcasters.

And the mission? How to monetize radio.

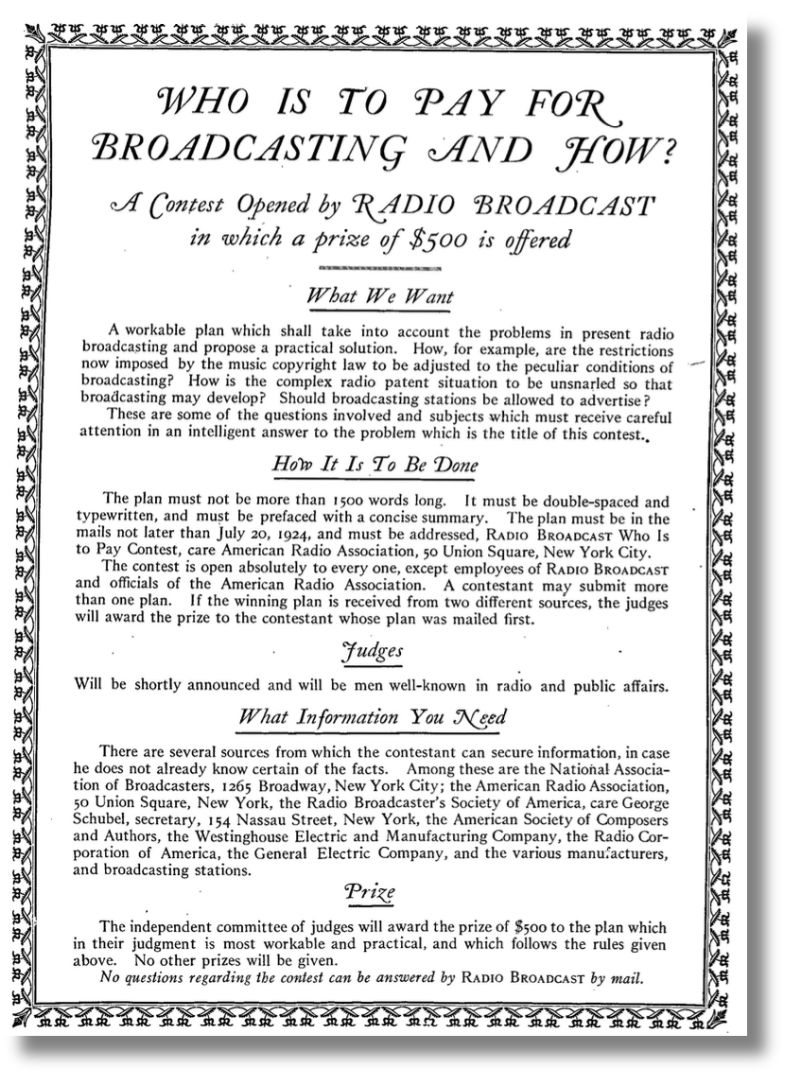

Barton explains the instigator of a crowd-sourced solution was the magazine Radio Broadcast offering up an impressive five Benjamins for the best idea to figure out the key question:

“Who Is To Pay for Broadcasting And How?”

A century later, it should not escape any of us these questions remain largely unsolved. Back in 1924, the prize was worth more than $9,000 in today’s dollars and Radio Broadcast’s bold competition attracted more than 1,000 contestants.

It is noteworthy the competition ended in frustration, making a statement about congenital roadblocks often put up by ownership throughout these past many decades.

Barton explains that in the early days of radio, many stations were owned by big department stores trying to sell…radios!

But the model didn’t work financially, forcing broadcasters to look for other solutions. While the “currency” today for commercial radio at least is advertising, back then, it was not a popular model right up to the way up to then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. Yes, the same guy who’s presidency is forever associated with the Great Depression.

If this is something anyone in radio today is interested in replicating, I can save you money, time, and attorney fees. Radio Broadcasting did the heavy lifting, and came up with the rules for the contest:

Back then, suggestions for how radio might pay for itself ran the gamut, including “slot machine radios.” Here’s the concept: You’d put in a nickel, the radio signal would “unscramble” for two hours of listening. What a deal!

In her story, Barton talks about other ideas that emerged, including a 30-day fundraising drive. (Don’t get any ideas, public radio!)

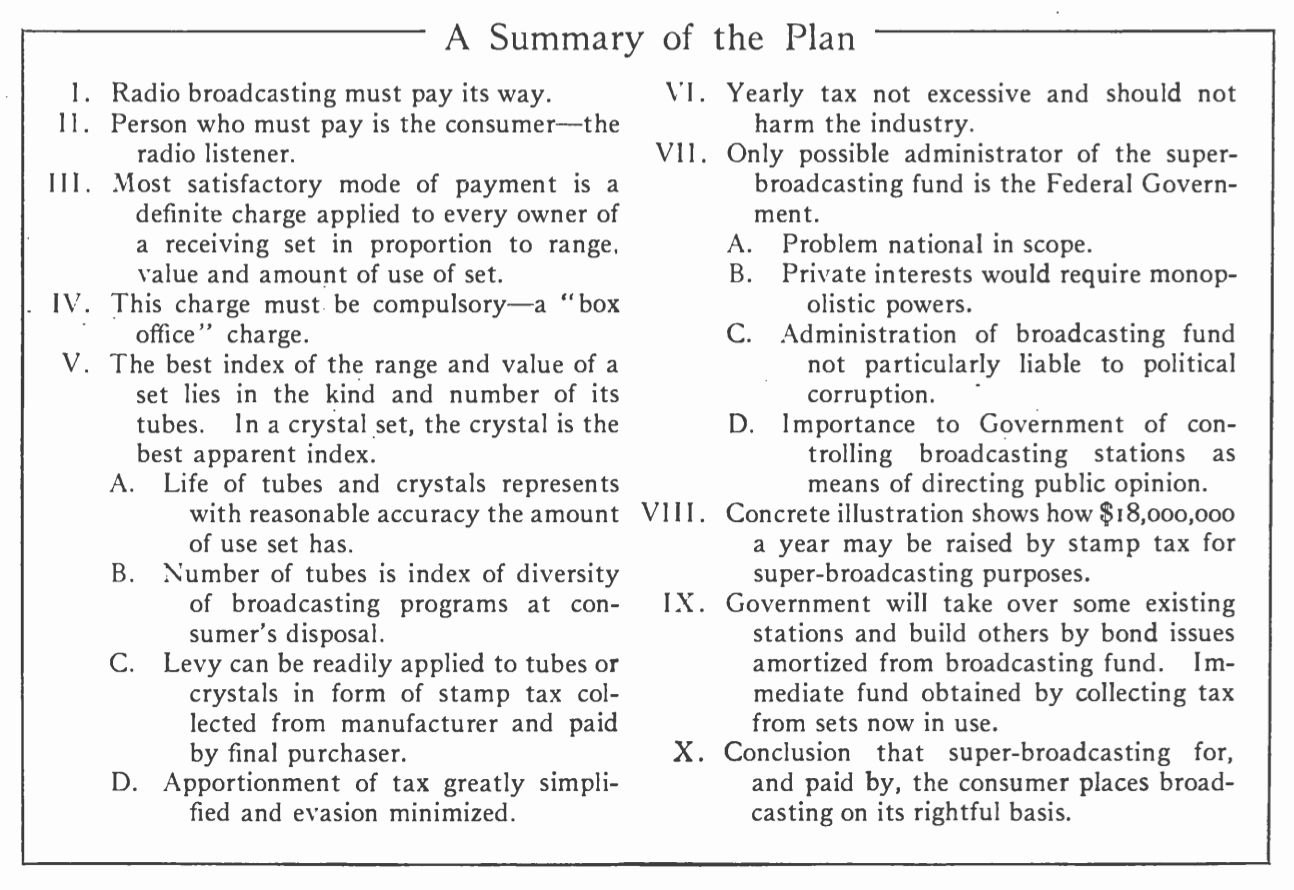

Finally, the Radio Broadcast contest produced a winner, a guy named H.D. Kellogg, Jr. In those days, radios were powered by vacuum tubes. His idea was a $2 federal tax on their sale (plus a 30¢ tax on each crystal sold). In many ways, this has similarities to the licensing fee charged to UK residents by the British government which funds the BBC.

Here’s how Kellogg mapped it out:

While Kellogg won the contest and the $500 prize, he didn’t win over the hearts and minds of radio ownership back in those seminal days. In fact, the head of the NAB, Paul Klugh, called the tax “obnoxious” and averred: “I don’t believe your prize-winning plan feasible under conditions as they exist in this country.”

Barton tells us the Radio Broadcast team wasn’t excited by Kellogg’s plan either, instead opting to do NOTHING. She quotes columnist Zeh Brouck who wrote, “For the present, I think it is better to let things ride along as they are.”

Sound familiar? Reactions to actually doing something bold or innovative in radio broadcasting generations ago echo the inaction of leadership years later.

And yet, advertising became the currency for radio broadcasters, a model that survives today in the commercial radio realm – for better or worse.

Herbert Hoover had a comment about commercial loads:

“The dignified presentation of the sponsor has too often been abandoned for hucksters’ tattle, interlarded into the middle of programs and tiresomely continued at the end.”

“Interlarded?” That’s a new way of describing bloated, excessive commercial stopsets, underscoring the reality we may not have made all the much progress in the past century.

Julia Barton wonders whether a new contest should be launched, addressing the same nagging question:

“Who is to pay for radio broadcasting – and how?”

But will anybody be listening a century later?

I “appropriated” the title of today’s post from one of the most amazing contests in radio history, Jack McCoy’s famous “The Last Contest” which originated at KCBQ in San Diego way back in 1971.

For radio old-timers, it was brilliant in every way – bombast, bigness, packaging, brilliant writing, amazing VO (McCoy himself) and stellar production. McCoy threw in everything in an effort to superlatively make a gargantuan statement.

You can learn about “The Last Contest” in an instructional video hosted by radio legend, Pat Holiday as part of his programming master class. It’s a fun ride, and a stark reminder about the power of “THINKING BIG!”

Here’s the video:

- Turn Up The Radio (If You Can Find It) - May 21, 2025

- Who At Your Station Would The Audience Like To Have A Beer With? - May 20, 2025

- Lessons For Radio From The Recent Google Home Outage - May 19, 2025

I worked for Jack for 4 years when I first started in radio; he taught me everything about bridging sales and programming, research and music scheduling and contesting. The winner in slow motion was because they guy couldn’t remember all the prize package numbers, He later reinvented the mechanics with The Checks in The Mail and The Incredible prize catalogue where i produced his promos for radio stations, it was an amazing experience. I’d spend hours looking for the perfect music bed to tell the story. The story is, the prizes were never purchased unless the winner chose them, it was all theater of the mind.

Yes, there was sleight of hand, but it was so brilliant. Thanks for sharing the story of working with McCoy. We need more big thinkers.

Fred: Loved this. Brilliant article. Magnifies that Radio has faced challenges for 100 years. I admire how your brain works and appreciate you sharing it so kindly to those of us who are still learning. Thank you.

I also enjoyed The Last Contest and worked with Jack several times in my career. I don’t know of many people who used the power of audio as brilliantly as did Jack.

Mike, I appreciate your comments and I appreciate YOU. You are a true believer, and we need more of you.

And I’m a little jealous you got to see Jack McCoy do his thing. What an exciting time for our business.

As you know, Fred, I’m a San Diego boy, and so you’ll understand why KCBQ was the single biggest influence in my life in wanting to be in radio.

You’ll also understand why, after a career in radio, when I think of my all-time favorite memories, a very top memory was the night the company I was working for at the time, Salem, which had purchased KCBQ and was temporarily simulcasting our station while setting up different programming, I got to say that legendary station ID live on the air. Seems like yesterday I was just about flying out of my seat nearly shouting, “KCBQ SAN DIEGO!!!” Long after its glory days, but still a dream come true.

The station I grew up on — the one where I was able to Meet the Beatles, the one where the Jackson 5 taught me my ABCs, the one where Three Dog Night brought Joy to my World — is no more. But the sweet, fun, joyous, exciting memories live on.

David, I’m glad the post resonated for all the right reasons. I remember the first time I heard those promos for “The Last Contest.” That production just jumped out of the speakers. I can only imagine what it must have been like in 1971, driving around San Diego, nnd listening to KCBQ. Thanks for chiming in.

Just hearing McCoy’s voice again made me smile, but then I had a more sinister thought.

What would happen if today, 2024, a new station signed on (pick whatever format you like) and just did the Last Contest with marketing (modernized just enough)?

Not that anybody ever will, but what if?

A thirty share?

Ah, well, thanks for the reminder that radio used to be BIG, and important.

It woud be fascinating to watch the reactions to “The Last Contest,” amidst a sea of $1,000 collective contests. I’m betting on Jack.