There was a time when I was pretty regular CNBC viewer. The moving stock ticker crawl showing each day’s financial market story was compelling to me, especially as I was trying to understand investing. Maybe “addicting” is a better word, because it can be pretty stressful monitoring your holdings, especially in an unstable environment where financial news of one kind of another can roil the markets in ways that seem unpredictable to novice investors.

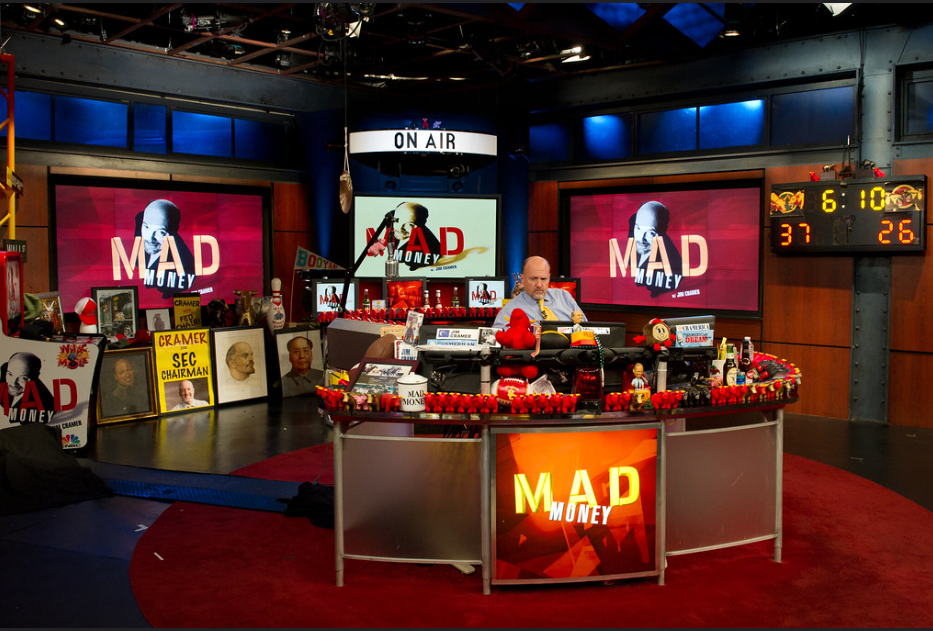

I learned my lesson during the crash of 2008-09, especially watching Jim Cramer, CNBC’s markets and investors whiz, and host of the long-running daily show, Mad Money. If Morning Joe is similar to an ensemble morning radio show, Cramer’s schtick is more reminiscent of a shock jock show hosted by a manic, highly caffeinated star, complete with sound effects, benchmark bits, sound effects (ka-CHING!), catchphrases (BOO-YA!), and plenty of phones from fan boys and girls who live and die by Cramers’ stock picks and his machine gun approach to making sense of the markets.

His persona is the sleeves-rolled-up, crazy but brilliant mastermind who has an opinion on everything, and whose delivery can shift from calm and sincere – your wise uncle who knows the street – to shouting, ranting, and arms-waving in a matter of seconds.

To me, Cramer can be unsettling. I always feel like I’m behind an imaginary curve when I watch him call the shots. But to the thousands who pay for the privilege of being members of his investment club to the tens of thousands of viewers who hang on his every word – or stock pick – Cramer is a guru, a god of the money markets who like many talk hosts, has an encyclopedic memory and the gift of gab. Powerful stuff.

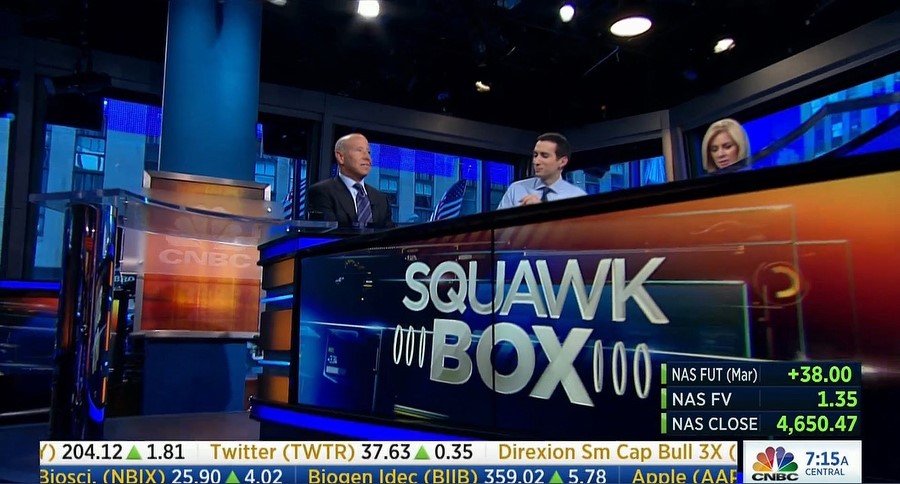

So, I don’t watch CNBC much anymore, especially in the Trump Era where I’ve come to realize the financial markets react as logically as the field of thoroughbreds racing in the Kentucky Derby or my March Madness brackets. But the other day, just before the bell opened, I punched over to CNBC and joined midstream in a market conversation on the networks’ morning show, Squawk Box.

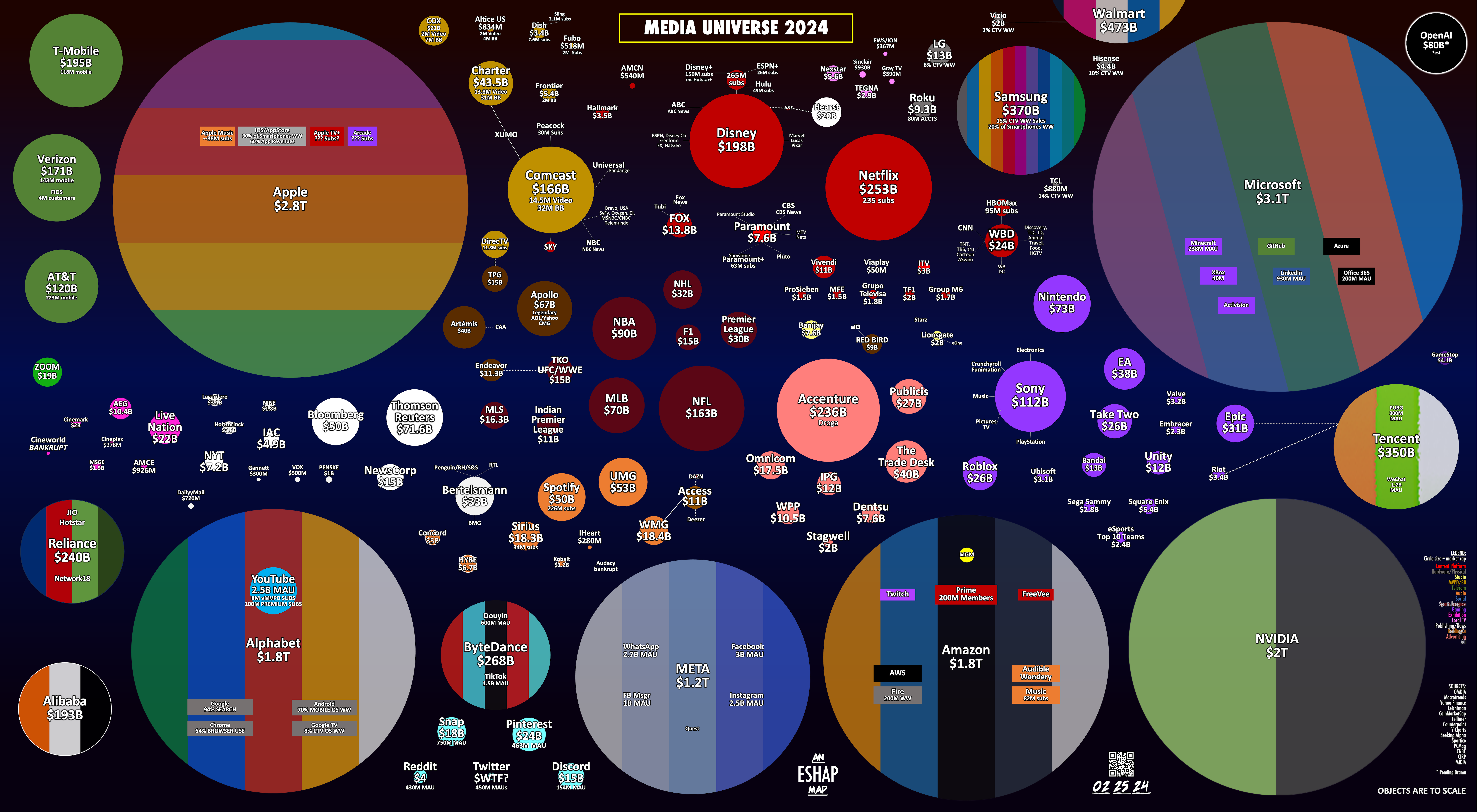

The anchors and analysts were in the middle of a conversation, marveling about the unbelievable size and scope of mega-companies like Meta (Facebook), Alphabet (Google), Apple, and Nvidia. They talked about how these amazing entities – known as “Trillion Dollar Death Stars” by Evan Shapiro (more on him in a minute) – simply lap the field of the rest of the tech industry in research, resources, and everything else. And forget tech. These companies’ scale is just massive, no matter the industry.

how these amazing entities – known as “Trillion Dollar Death Stars” by Evan Shapiro (more on him in a minute) – simply lap the field of the rest of the tech industry in research, resources, and everything else. And forget tech. These companies’ scale is just massive, no matter the industry.

And then the conversation shifted to an earnings report that just came out for Macy’s, the department store chain that like others in their category, has struggled in recent years. They declared bankruptcy back in ’92, and continue to flail around, recently announcing 150 store closures over the next three years. And as one host remarked to the other: “Macy’s? There’s like seven people in the world who care about their earnings,” implying the once mighty retail shopping brand was a shadow of its former self, but also that in the big scheme of the financial ecosphere, Macy’s is now peanuts, chump change.

I flashed back to that famous black and white Christmas movie from the 1940s, Miracle on 34th Street that takes on the classic adolescent controversy “Is Santa Claus real?” through the character of Kris Kringle, Macy’s “Santa,” and a little girl played by a very young Natalie Wood. The movie’s backdrop is the main Macy’s department store in New York City, engaged in a heated competition for holiday shopping with its nemesis, Gimbel’s. Now decades later, Gimbel’s is no more, and Macy’s is fighting for its life.

And yet, Macy’s has a market cap of nearly $6 billion – not chopped liver. But in this world of massive corporate city-states like Microsoft and Amazon, Macy’s is a very small player in the economic mainstream of 2024. The CNBC hosts quickly recovered from their smartass Macy’s comment, probably out of fear over the expected complaints – from Macy’s and whoever is the showrunner for Squawk Box. But their sarcasm about a lack of interest in a minnow like Macy’s was not lost on CNBC viewers – or me.

To get some perspective, below is the updated look at the solar system of entertainment from Evan Shapiro who I’ve written about in past posts here on the JacoBLOG. This most recent map looks looks at the Media Universe (so far) in 2024.

Those “Trillion Dollar Death Stars” are highly visible as the size of companies and corporations are drawn to scale, based on their current value. As you scan this universe, you’ll see a lot of familiar names – MLB (and other sports leagues), Nintendo, Paramount, and even Live Nation and Universal Music Group. In the big scheme of things, they actually appear to be rather small, in spite of how we perceive them as consumers or even investors.

What you won’t see are the radio companies you read about every day in Inside Radio, Radio Ink, and Jerry Del Colliano (if that’s your thing) – unless you’re using a powerful magnifying glass. With the exception of iHeartMedia (a tiny dot) and a notation for Audacy Bankrupt (no dot), radio broadcasting as we know it is too small to see with the naked eye. If you’d like to play the radio version of “Where’s Waldo?” go ahead and look for iHeart (clue: they’re next to Sirius) or scroll to the bottom of the post for the reveal.

In CNBC lingo, maybe three people in their world really care about what happens to radio companies anymore, besides all of us trying to still make a living in the business. In the vast ocean of the financial world, we’re plankton among the whales, the sharks, and the myriad of other underwater life.

So, why does this matter on a Monday morning in late March of 2024? Why am I leading off a perfectly random week with a seemingly downer post like this one?

It’s because I continue to be reminded about radio’s place – especially in focus groups where the emphasis isn’t always on “So, what’s your favorite radio station (if you had to choose just ONE?”). When respondents are free to talk about the other media in their lives beyond radio, they are usually quick to rattle off the big names and verticals: Spotify, podcasts, satellite radio, YouTube, social media, video games, and of course, Netflix, Hulu, Peacock, Max, and all the other video streamers. What am I missing? Plenty, and much of it is depicted in smaller spheres on Shapiro’s map.

In the familiar refrain you’ve heard from me in speeches, presentations, and here on this blog, your radio station doesn’t just compete against B93, the Eagle, that NPR News station on the left end of the dial, or that new Christian music network that just appeared out of nowhere in your Nielsen ratings. You’re now up against many, if not all, of the entities pictured on the cartographic creation from Mr. Shapiro. Like we love to say here in Detroit, it’s us against the world – or better put, the universe:

The shirts are cool. (Why on earth didn’t I market them?) But the reality of the competitive situation is anything but.

Radio is like the rebel force up against 100 Death Stars. In other words, not a fair fight. Not even close. That’s because our new media competitors have everything – research, marketing, armies of sellers, tech expertise, Wall Street bucks, brain power, aspiring brilliant kids who would kill to work there, even marketing, and reams of user and market data.

Their goals may be different, but they are all vying to innovate in their space. We see it every year on display at CES, where companies as diverse as John Deere, Walmart, Delta Airlines, and L’Oreal are duking it out to see who can do the most innovative stuff.

And conversely, most radio companies of size are slugging it out for sheer survival. Many have gone without research, not for quarters, but years. Marketing? What’s that? And rather than hiring to grow, they’ve been systematically reducing staff for years now.

Interestingly, many smaller radio companies that serve smaller metros are thriving. That’s not an accident, a fluke, or an anomaly. We’ll come back to them before we’re done with this conversation, including some real world examples.

Back in my day – just to date myself even more than usual – any AM or FM radio station in Detroit, Dayton, or Des Moines competed directly with local TV, hometown newspapers, maybe a billboard company, and the Yellow Pages for advertising – and for attention. Yup, it was a knife fight that anyone could win with a sharp blade – creativity, a great team, community presence, and local personalities that mattered. Pretty much everyone competed vigorously for a nice pot of dollars at the end of the media rainbow.

Now, fast-forward just three weeks from right now, and we’re going to return to the site of CES – Las Vegas and its vast convention facilities in our annual celebration of broadcasting – the NAB Show. The exhibit floor, panels and keynotes, badges and lanyards, cocktail parties, meetings at the bar, and all the other trappings of a big-time media industry will be on display.

Except our world has changed – drastically – as evidenced by the math: stock prices, audience size, and market influence: especially in the biggest metros. Yet, we’re still partying – and often acting – like it’s 1979. But it’s not.

With the possible exception of iHeart – let’s give them credit for a solid plan: success in streaming and mobile with iHeartRadio, a robust podcasting foothold, bigger-than-life events, the only national rep firm still  standing, and the ability to scale their content and sales marketing initiatives – broadcast radio’s competitive landscape has been altered – OK, disrupted, if that makes everyone feel better – by technology and bold visionaries with the drive to innovate. And yet as many of you no doubt will fire back, iHeart declared bankruptcy exactly six years ago this month, along with the other two major players, Cumulus in late 2017, and Audacy this year.

standing, and the ability to scale their content and sales marketing initiatives – broadcast radio’s competitive landscape has been altered – OK, disrupted, if that makes everyone feel better – by technology and bold visionaries with the drive to innovate. And yet as many of you no doubt will fire back, iHeart declared bankruptcy exactly six years ago this month, along with the other two major players, Cumulus in late 2017, and Audacy this year.

True that. But among radio companies in the U.S., they have no equal – and aren’t likely to. For everyone else, it’s about finding that niche, a comfortable operating position where goals are attainable.

That may sound simple enough until you try it in the headwinds of today’s media universe. When we pull back and look at the detail of Shapiro’s media map, we see an interesting situation shaping up.

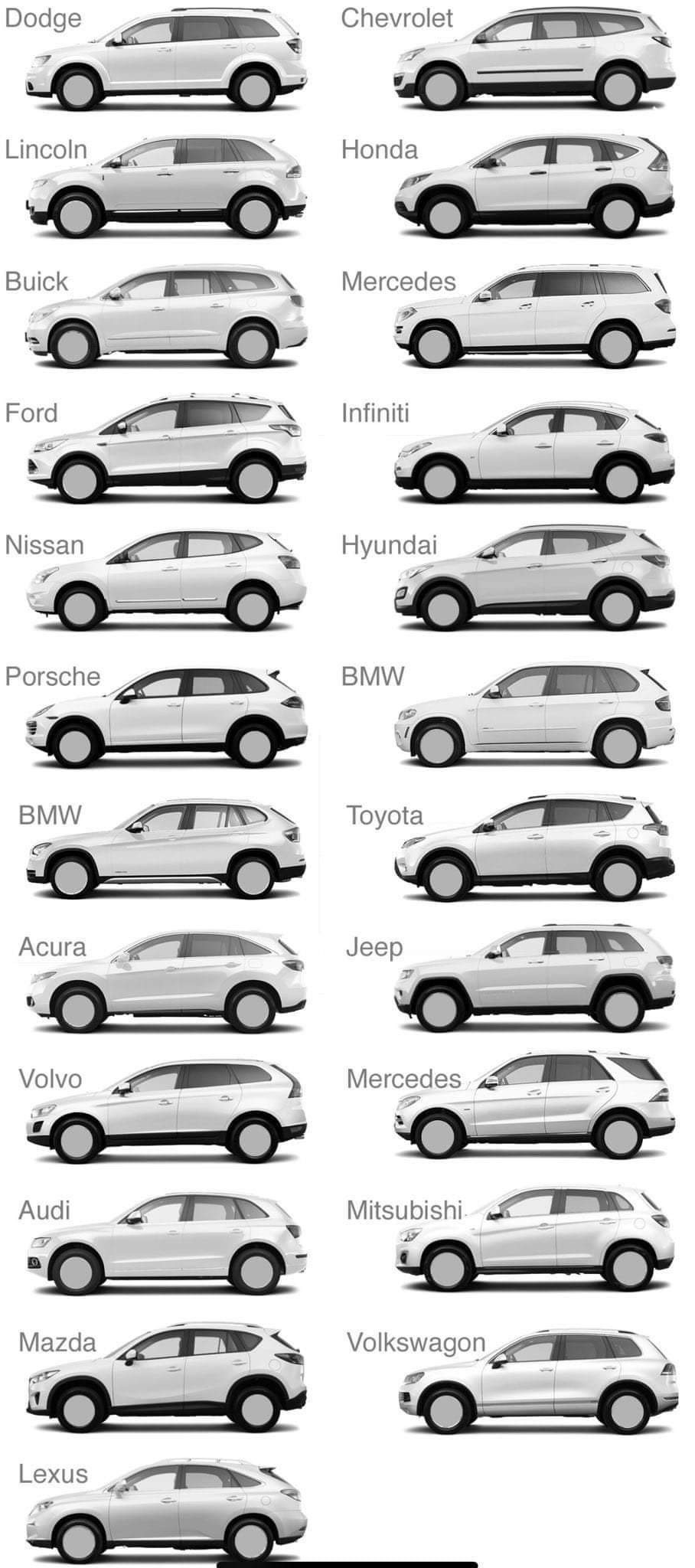

Many companies have achieved a high level of quality – products and experiences. In a recent MediaPost essay, J. Walker Smith points out that many consumer goods companies and brands are producing truly great stuff. But as the costs of competing have been equalized – we all have access to ChatGPT whether you’re Elon Musk or a Hot AC program director – everything resembles everything else.

I talked about this in a blog post back in late 2022 titled “Still The Same.” It made the point that in the auto industry, technology, efficiency, and know-how are pretty much ubiquitous. The moment one manufacturer innovates a feature or technology, a couple dozen others quickly follow suit, neutralizing any edge that may have existed. Whether we’re talking fuel efficiency, safety, infotainment systems, looks and trim, they’re all pretty much on par with one another. They even look the same.

As J. Walker Smith avers, AI will only prove to be a more efficient, accessible equalizer, thus worsening what he calls “the paradox of quality” – that is, “the better our products get, the more they are alike.”

Are radio stations that different? They all have access to the same research, the same monitoring services, and the same prep services. And all that attainable quality has led to similar clocks, the same short playlists, similarly looking logos, nearly identical group contests, and even personalities that are pretty much interchangeable. It’s no wonder many consumers feel FM radio stations so often sound the same. It’s because they do.

While radio has become adept at copying the industry standard, competing with the entertainment and information services provided by the big boys and girls hasn’t come so easy. In fact, radio cannot compete directly with streaming products and other content offerings from Apple, Spotify, Google, and others. And consumers are showing us they’re willing to pay every month for the privilege of not having to put up with commercials. They’re more than willing to pay that tariff.

J. Walker Smith reminds us that while quality is the stuff that builds brands, it is about the difference that drives relevance to consumers and gets their attention:

“The challenge of brands is difference. It’s the same challenge as always except that quality is no longer a reliable or sustainable way in which to create and deliver difference. For many categories, quality has become table stakes.”

become table stakes.”

For radio broadcasters, it’s a struggle to even keep up, much less outdo the newer players in the entertainment ecosystem.

It will boil down to how radio broadcasters can establish not just a difference, but one that matters.

So hang on tight – that’s where I’m headed tomorrow.

P.S. iHeartMedia’s location of the Media Universe 2024 is just a click northwest of Meta.

P.P.S. To locate sessions and panels at the NAB, click here.

P.P.P.S. To read Part Two of this post, click here.

- Turn Up The Radio (If You Can Find It) - May 21, 2025

- Who At Your Station Would The Audience Like To Have A Beer With? - May 20, 2025

- Lessons For Radio From The Recent Google Home Outage - May 19, 2025

Fred, Your graphic of the same looking white SUVs is pretty startling. Just like music and speech, broadcasting doesn’t have to be the same. Sobering Monday morning thoughts for innovation.

FWIW, one of my regular FM go-tos here in Maine includes in every liner its slogan: “Different is good.” Maybe they’re onto something?

(h/t WCLZ)

The graphic makes you stop and woonder why seemingly every station (and company) seems to be headed down the same tired path.

I believe a key word in your sentence there, *is* “tired”.

Yeah, Fred that graphic of the similarity of all those SUV’ is exactly why when I wanted a “new” car I had to buy a 2020 because I didn’t want an SUV and didn’t want to look like every other car on the road. It further illustrates, as you are so good at doing, the McDonalds-isation of the radio business. Using the T-bone steak analogy in the world of radio it’s RARE when the MEDIUM is WELL DONE or done well and I’ll stake my reputation on that. Keep up the good fight Fred and maybe at some point the industry will wake up and listen…and perhaps the audience will too!

Funny you say that, Art. I was driving a very nice Lincoln SUV until the lease expired. I thought it might be a nice change to drive an actual car. So I asked my Lincoln sales guy to show me the new Lincoln sedan. He pointed to the showroom floor and said, “Do you see any cars out there? We don’t make ’em any more.” Wow. Thanks for the comment and the kind words.

Hey Fred, your blog is my thing every day. Keep up the thoughtful writing.

This much appreciated, particularly coming from one of the most prolific and clever writers in the business.

Jerry loves the bad news ones the best 😝

Jerrrrry!

hi.