Many of us have a vivid memory of creating playlists and mix tapes, often on cassettes or even open-reel tape. A party playlist, a dance playlist, a workout playlist, and even playlists dedicated to a lover, friend, or person who matters to us could consume hours of careful thought and preparation.

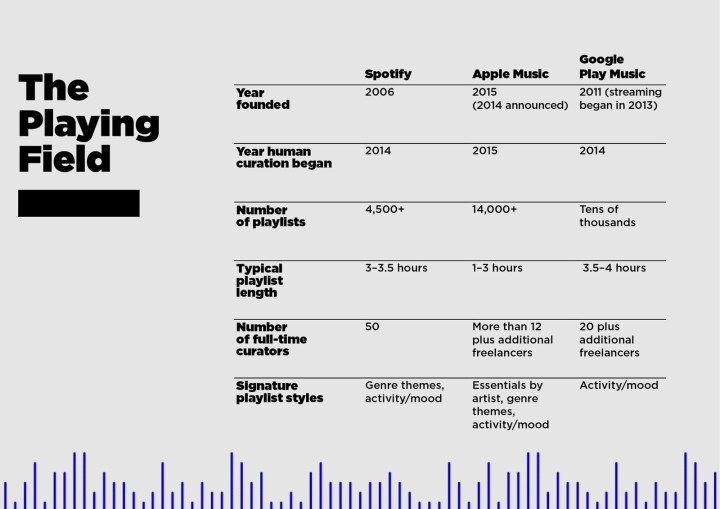

Here in 2016, when it comes to some of the biggest names in the streaming radio ecosphere, more and more it is about the playlist. And to that end, pure-plays that include Apple Music, Google Play Music, and Spotify all started hiring human programmers at about the same time. They don’t call them P.D.s, but the bottom line is that people have been added to algorithms in order to ensure these services maintain high rates of success, while serving subscribers.

According to a fascinating analysis from BuzzFeed written by Reggie Ugwu, all three of the aforementioned pure-plays have all begun “human curation” to create playlists during the past two years. Interestingly, they don’t call these people Program Directors, but they could be referred to as “Playlist Directors” because that’s what their jobs entail.

Spotify, Apple Music, and Google Play Music now offer thousands of playlists available to their respective user bases. And unlike the way broadcast radio does it, “activity/mood” are the drivers behind most playlists, overshadowing traditional formats or genres.

Why the shift to curation as opposed to simply relying on users to pick and choose their own playlists? The article quotes Jay Frank, SVP of Universal Music Group’s global streaming marketing:

“All the signs point to playlists being the dominant mode of discovery in the near future…People go to streaming services because they love the idea of being able to listen to all the music that they want, when they want it. But then when they get there, they find that may not actually be what they want most of the time. The prospect of digging through 40 million tracks is just too much.”

For more and more people, it’s overwhelming and it’s too much work. And that’s why playlists are becoming more and more popular in the music streaming ecosphere. Consumers want somebody else – hopefully, someone with great taste – to do the heavy lifting for them.

Spotify now reports than half of its 100 million+ users around the world are listening to music programmed by someone else. Some experts say that 20% of all songs streamed today occur within a playlist.

A few interesting facts about how the pure-plays do it…

A few interesting facts about how the pure-plays do it…

They have data, and lots of it, enabling them to better tweak, hone, and craft their playlists on a song-by-song, moment-by-moment basis. Just like in broadcast radio, some songs turn out to be “stiffs,” while others “burn” (yes, the article uses that familiar radio term). Sometimes problems arise with sequence or flow – in much the same way broadcast radio’s PD’s nuance music scheduling rules and codes.

Spotify uses a system they call PUMA (Playlist Usage Monitoring and Analysis) which provides their human curators with data that include plays, skips, and saves, along with demographic data that goes well beyond Nielsen’s age, gender, and ethnicity. Time of day, geography, and even subscription tier (think P1s and P2s) come into play as well.

The emphasis on mood and activity are areas where broadcast radio PDs might give some thought. Spotify, Apple, and Google have metrics that show how consumers gravitate to playlists that exude a certain feeling or energy, rather than simply creating playlists around a format – like Classic Country or Urban AC.

It was a reminder to me of a music test I moderated many years ago. At the end of the evening, a respondent walked up to me and told me how much he had enjoyed rating all 600 hooks. But then he said, “But had this test happened at 8 in the morning instead of 8 at night, I would have rated the songs very differently. It’s a mood thing.”

While broadcast radio has never really taken into account ever-changing and shifting emotions when it comes to music, these concepts are researchable, allowing for programmers to at least understand and accommodate mood shifts. “The Quiet Storm” and Sunday morning acoustic shows all catered to moods, times of day and mindsets – right along the same lines those human curators at the pure-plays are thinking.

A number of these pure-play’s “human curators” were mentioned by name and shown in pictures in the BuzzFeed article. To my knowledge, not a single one comes out of radio. It appears these curators are selected more because of their passion for their particular music discipline than anything else.

Sure, radio has been involved in “human curation” since the medium’s inception, but the popularity of pure-plays and playlists begs the question why broadcasters could not adopt some of the same basic practices. This includes using some of this new jargon when discussing what it is we do: curation, playlists, activity, and mood. Whether it’s communicating radio’s virtues to advertisers, coaching air talent, or even better understanding our jobs, thinking about how the time-honored task of programming music is changing because of technology is a healthy process.

Why radio’s programmers couldn’t post online playlists to showcase local music, tertiary sounds like metal, folk, and other musical tributaries seems like a wasted opportunity. And of course, there’s the mood thing – a perfect opportunity to create playlists to match the market’s attitude, whether it’s the first snow, opening day, or a big party to start a three-day weekend.

It could lead to members of the airstaff becoming engaged in creating playlists, thus igniting their interest in music, rather than sitting back and mindlessly following a computer-generated log. And it could generate audience sharing, and maybe even reimagined bar nights where listeners are challenged to create their own playlists.

Radio may always be radio – a medium curated by program directors, whether they’re living in the market or creating them virtually from another outpost. But the industry should be mindful that streaming radio has rewired consumers brains, changing expectations and preferences about the way music is programmed, discovered, and enjoyed.

The NPR One app has proved that digital applications and learning can be applied to conventional programming constructs. The ability to skip, share, and designate news stories and features as “interesting” has provided NPR with a treasure trove of data that can bring a new understanding to the time-honored art of radio journalism. And the result is a platform where news pros and programmers are learning new things about the news writing and news gathering process leading to larger and more satisfied audiences.

Spotify, Pandora, and the others have learned a great deal from broadcast radio over the years about playlists, music scheduling, dayparting, feature programming, and other variables that go into creating a satisfying experience.

But now the tables are turned, and music programmers in the broadcast space have a lot to learn, too.

To very loosely quote William Shakespeare, “The playlist’s the thing.”

- Why “Dance With Those Who Brung You” Should Be Radio’s Operating Philosophy In 2025 - April 29, 2025

- The Exponential Value of Nurturing Radio Superfans - April 28, 2025

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

A limiting belief of radio is that we only need to produce 24 hours of content per day, which is all that can be broadcast over the air.

As local audio brands (stations) transcend the tower and use technology to provide their audiences with more than 24 hours of programming (perhaps 100 hours per day or even 1000+ of curated content and playlists, a variety of opportunities begin emerge that transcend the limits of a singular audio product.

We’ve gone from an era of scarcity with tremendous barriers to entry to abundance.

Exactly, Andrew, and thanks for making this point. We have long perceived our content to be disposable. It airs and it’s over – one and done. Technology allows our creations to have “legs” (assuming it’s any good), available for sharing and repeated use. The barriers are indeed down, but a shift in mindset is necessary in order to realize the possibilities. Thanks for adding to the conversation.

It’s fine to me that all that music is available. But radio is still a “broad” cast medium. I don’t see the day when a single radio station will EVER sound like a pure play. Did you ever watch someone listening to Pandora? Or Apple Play? Or even You Tube? When it hits a song the listener doesn’t like or find interesting, it causes them to tune away…to their own collection on their phone, to another service, or even (Gasp!) to AM/FM radio.

Radio could use some of this in terms of specialty features at certain times of day where it makes sense. (I am doing this now on a market leading country FM, and have plans for other musical features for it.) This could return radio a bit toward a more “unpredictable” sound similar to the AOR stations of old, and to a more “regional” approach in scope which would eliminate some of the complaints about the “sameness” of stations today.

But as long as radio is trying to go for the masses, instead of individual listeners, it will be impossible to see radio playlists of thousands and thousands of songs. Though the internet could cause us to rethink how we present the musical content online and, to a degree, and could lead to a degree of what a lot of us in the business miss…the ability to be creative with our presentations.

Kevin, you make an accurate point when you discuss the need for broadcast radio to be mass appeal. But our online assets (or even our HD2 stations) don’t have to adhere to the same limitations. Radio may never be like a pure-play, but programmers have the ability to provide playlists, secondary streams, and HD channels to the mix apart from the “mother ship.” Thanks for the comment.