Yesterday’s blog post stirred up the expected conversation about the music industry and radio. Like the debates about guns, abortions, vaccines, and masks, everyone has an opinion. In fact, most of them are fervent.

The post focused around a opinion piece in The Atlantic penned by Ted Gioia, declaring – for all intents and purposes – that new music has seen better days. Gioia pulled data from different sources to make his point that the record labels have all but thrown in the towel on discovering new artists and groups, instead focusing on the green pastures of catalog music.

Some of you took exception to his analysis, pointing to everything from misreading the charts, how “new music” is categorized (18 months old or newer) to overemphasizing falling Grammy Award ratings.

I get it. I had some of the same visceral reactions to Gioin’s piece the first time I read it. And then I re-read it, and started thinking about the bizarre collaboration between the music industry and radio broadcasters to essentially do very little to expose the world to new music with the effort and force of past decades. Ironically over the past couple decades, consensus about anything between “radio and records” has been nonexistent. In fact, the two industries have been locked up in a Holy War over royalties and compensation to a point where they have each devalued the other’s contributions.

But the one thing they both apparently agree on is that to get behind new music is a bad model. As Gioia points out, the labels have done very little to discover “what’s next?” opting instead to focus on the profitability of vinyl, catalog sales, and recently publishing rights negotiated with some of the industry’s biggest and most successful artists.

Radio, in the meantime, once a true reflection of music and talk tastes that appealed to people from 12 years-old to death, has instead been playing it safe for decades, choosing to play the 25-54 game, the “sweet spot’ where most agency ad buys are centered. AM and FM radio stations were once the bastions of new music discovery, eager to expose and champion new music – and the teens and twentysomethings who couldn’t get enough of it. And in many cases, record companies and concert promoters supported these efforts with ad buys, promotions, interviews, and appearances.

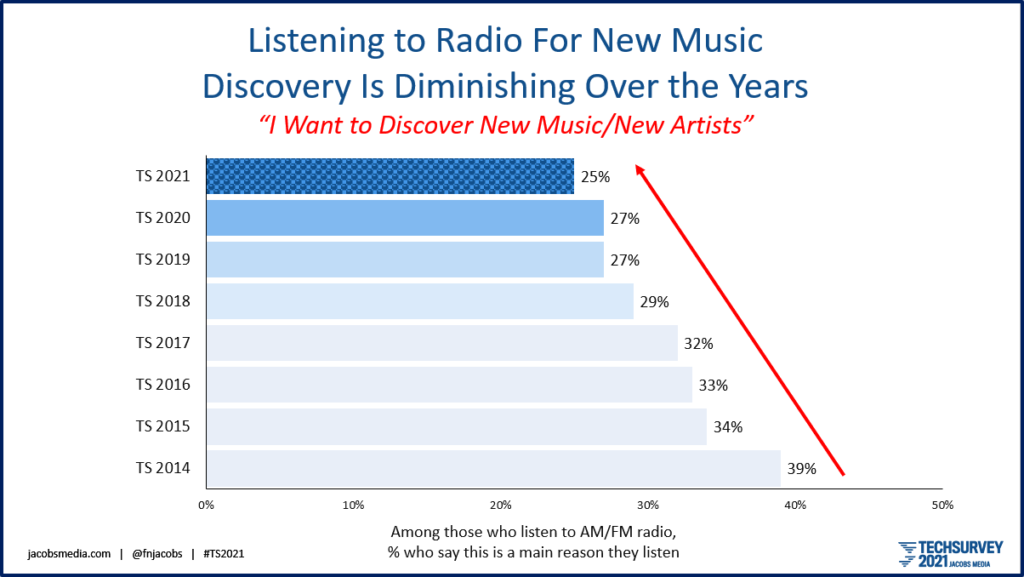

And the fruits of radio’s efforts to narrow its focus – or more to the point, its stagnation – has produced an odd effect where no single source of music exposure can truly carry the weight. We track the percentage of Techsurvey respondents who tell us a main reason they listen to broadcast radio is to discover new music and new artists. Like many of Gioia’s charts, it tells a story:

Yes, our sample is comprised primarily of radio fans. And yes, they are aging. But the trajectory here is unmistakable. Broadcast radio has many great qualities and discernable assets. Unfortunately, playing and exposing new music is rapidly becoming a non-factor in the platform’s appeal. Radio has abdicated that role, and has seemingly little desire to win it back.

As I was writing yesterday’s post (on Monday), a tweet came flying in from Abbey Minke, a radio personality in St. Cloud, Minnesota. And it lit up my Twitter feed:

There’s no denying the popularity of “When We Were Young Fest”, but it begs the question: where is the terrestrial radio format that plays that music?

The demand is obviously there, in a demo willing to dish out cash. Something to think about. (Or for @fnjacobs to write about)

— Abbey 📻 (@AbbeyOnAir) January 25, 2022

it spurred a long discussion about drawing the lines of nostalgia – where they begin and where they end, what IS classic?, and when and if the 2000s will spur a new format aimed at those who grew up 20 years ago, ready to enjoy the music they grew up with. Others talked about a theme Ted Gioia addressed as well – the quality of new music coming out today.

Abbey, a challenge with architecting a new radio format that focuses on that decade circles back to the highly fragmented ways in which Millennials were exposed to that music in the first place. If you’re a Millennial, you grew up with iPods, video games, Pandora and Spotify, TV and movie soundtracks, and untold other sources of music. And yes, radio, too.

In the aughts, as it is today, everyone’s experience with new music was unique. Building a 2000’s-era music format designed to cater to a broad coalition of fans is fraught with challenges. In retrospect, creating formats like Oldies and Classic Rock was relatively easy because everyone’s first exposure to the music from those respective eras and genres was the same – on the radio.

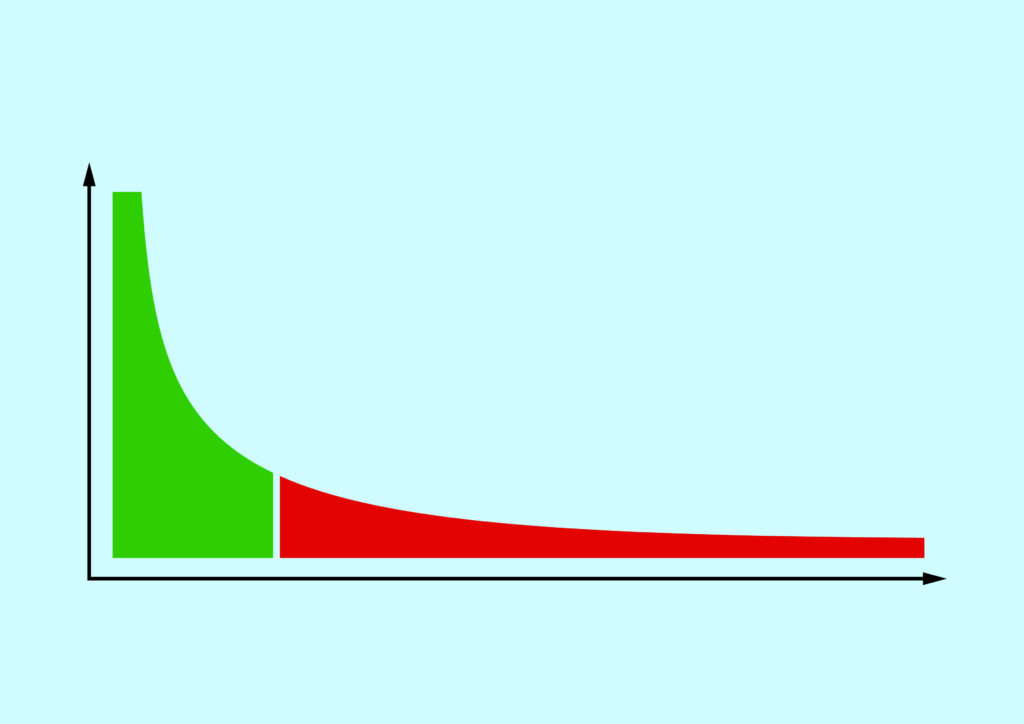

Today’s means of discovering new music is splintered into hundreds of media points – a long tail of outlets where one can hear any variation of new music. And none of these has an audience “mass” enough to truly shape tastes – like radio did.

It’s the story of “the long tail,” a concept developed and defined by Wired’s Chris Anderson nearly two decades ago that explains, in large part, why our music world is devoid of big, mass appeal hits. Come to think of it, with the exception of anomalies like the Super Bowl, smash successes in the worlds of movies, TV shows, books, and other cultural outlets are few and far between. Even though the population has grown and media access has exponentially improved, we’re all watching and listening to different stuff. Better put, we are our own programmers – and distributors.

Here’s how Anderson put it back in 2004:

“Up until now, the focus has been on dozens of markets of millions, instead of millions of markets of dozens.”

Yes, that’s AM/FM radio in green: a lot of exposure for a finite number of songs, heard again and again on hundreds (and even thousands) of radio stations. That’s how you “make” hits – playing great songs with force and yes, repetition. And when those songs are played on multiple outlets in a metro – and eventually, in cities and towns all over the country – you have smash hits.

And then there’s red part, the “long tail” of today – a splintered environment of music of eclecticism and personalization across numerous outlets, gadgets, and platforms. The proliferation of radio stations across all those outlets has democratized music, while diluting to a point where big hits are few and far between.

In his Atlantic article, Gioia expresses the hope that when “the next big thing” comes along, we’ll know it. But that’s like waiting to win the lottery. And while artists the caliber of Sinatra, Elvis, the Beatles, and Michael Jackson may never come along again (I don’t believe that, by the way), responses to Abbey’s tweet and yesterday’s post suggest many of you believe great new music is “out there.”

And that’s why I end up back where we started from – radio. In Gioia’s analysis, he is generally dismissive of radio, describing it as only a small part of the problem:

“Radio stations are contributing to the stagnation, putting fewer new songs into their rotation, or—judging by the offerings on my satellite-radio lineup—completely ignoring new music in favor of old hits.”

Technology may have changed the way we discover new music (or don’t), but radio has been an active co-conspirator by failing to wave the new music flag. Like in Ted Gioia’s essay, most music observers write off radio as a medium of the past that “no one listens to today.”

But the fact is, radio is the last mass reach audio platform left. For all the gains amassed over the past decade or so by SiriusXM and Spotify, their “cumes” are still dwarfed by radio. And even if they were able to engineer a growth spurt, they are, by definition, fragmented to begin with – hundreds of channels, millions of playlists – the long tail.

I am often asked why Classic Rock worked. And while the planets lined up perfectly in the early 80’s when I was launching the format, America was ready to hear music from the 60’s and 70’s.  When WMMQ in Lansing hit the airwaves 37 years ago this spring, the radio airwaves were loaded with “Hot Hits” – new music in rock, pop, and other genres. MTV had recently debuted, putting the focus on new and now.

When WMMQ in Lansing hit the airwaves 37 years ago this spring, the radio airwaves were loaded with “Hot Hits” – new music in rock, pop, and other genres. MTV had recently debuted, putting the focus on new and now.

When the pop culture world gravitates to one end of the spectrum, there is often a lot of shares available on the other end of the spectrum. That was the audience “real estate” Classic Rock quickly captured. And in typical radio fashion, success in one market always spawns imitation and duplication in other places. By the end of 1986, there were Classic Rock stations in D.C., Boston, Atlanta, L.A., Detroit, Chicago, and many other cities and towns all over the U.S.

I’m a believer a radio company dedicated to trying something different with a perennial loser could launch a new station that plays nothing but new music. I don’t know what this station would sound like, but it could take advantage of the crowd-sourced, voting, and exposure elements that are now easily accessible parts of the digital took kit. It would have to have a strong video component, maybe a concurrent stream.

I do know it wouldn’t be programmed by a bunch of old radio souls, but should clearly be the province of a new generation of programmers – just like many of us where back in the 70’s and 80’s.

Could a radio station today ever be as influential today as KHJ, CKLW, WMMS, or WBCN were “back in the day?”

Not a chance. Too much of the media landscape has changed – forever.

But in a world where consumers are looking for something new to embrace and radios are still front and center in most cars, radio still has a voice. The question is, does it have anything left to say?

But in a world where consumers are looking for something new to embrace and radios are still front and center in most cars, radio still has a voice. The question is, does it have anything left to say?

For those of you scoffing at the idea that radio could be an integral part of the solution, think about the ascent and resurrection of vinyl – another old, tired music format that has achieved new levels of popularity – especially among younger generations unaware of terms like “B-sides” or “cue burn.”

Of course, this requires an owner ready to try something unique, different enough to capture attention and generate some buzz. It must be a broadcaster who still believes in the power of radio as an influential, taste-making medium, and not just a megaphone to drive ears to podcasts and landing pages. And it would, by definition, just play new stuff, without fear of alienating “the adult demos.”

Could it happen?

Is there anyone bold enough to design and launch a radio spaceship in 2022 that could go the distance?

Is there enough great new music out there to power this experiment?

And will there be sufficient audience in our A.D.D. world to even give it a listen?

Would the music industry step up and support it?

Just like “the next big thing” in music, the “next big thing” in radio won’t sound like a radio station we’ve already heard.

That’s OK.

We’re all tired of the same old thing.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Well, there’s your format. “The world’s ‘last’ all vinyl radio station” Now wouldn’t it be fun if you could debut it on the old 97GTR frequency in Miami. The circle would be complete.

There you go – what goes around, right?

Time marches on. Technical Invention is accelerated on many levels. Fragmentation will continue. We will never have a mass media concentration of audience as there was in olden times. Which challenges us to expand our reach through multiple devices. The young minds who can create change will come from many places beyond radio. We need to welcome them and learn from them. Great two-part blog Fred. Well done.

I love when my blog posts pass the “McVay Test.” Thanks for engaging on this one, Mike.

As mentioned above, video would need to be a part of it. With feed sources like HD radio .2-.3, 5G smart phones, as well as smart TVs with ATSC 3.0, and the auto’s (future) center stack, the early MTV format can be dusted off made local / regional, portable and viable through all of these feed sources to the 18-34 lifegroup. All it takes is money. Lots of money.

And time. Sadly, we’re running low on both, Joel.

Great two-parter, Fred. If you and anyone reading this aren’t on the Pho listserv, I recommend it for its high-level discussions of media evolution. I’ve been reading it for 20 years, and I wouldn’t have my current job without it. The catalog discussion ripped through Pho with interesting inputs.

I grew up listening to WNEW in its glory years. Every day at school my friends and I would talk about what Alison Steele played the night before. There was no such thing as listening to decades-old music, which existed in our minds as a vague repository of ancient styles, like a museum that you visit on special occasions. (Not counting classical.)

With the shift to streaming, there’s no such thing as a dusty old collection. Spotify is egalitarian when it comes to music eras. Starting in the mid-aughts, Pandora’s Music Genome tech served up tracks based on sonic attributes, not production date.

This age-agnostic shift is basically a technology play designed to strengthen customer retention. Discover Weekly, Pandora’s “Thumbs” playlist — these and dozens of other popular curations are age-blind, reflecting an era in which there is no viable distinction between “current” and “catalog” — except when the user wants that division.

I’m not pretending to solve the trend you’ve written about. But I think these observations are pertinent. I have no idea what radio should do. 🙂 Cheers.

Can you give us a link to the Pho listser?

Brad, I enjoyed this comment and the perspective you bring. I did not know you were a child of “Where Rock Lives” – an amazing station that broke the rules and lived the dream. Like a lot of those stations of that era, they blazed a trail, sometimes a messy one.

I appreciate your observations about the vintage of music – and its irrelevance. I believe the iPod (and our “guilty pleasures”) played a role in that, too. People like a sense of randomness, but many appreciate a curated experience, too. finding that “sweet spot” is a tough putt. I don’t believe I have the answers either, but it’s a discussion we should be having. Thanks!

And let’s not forget the role Arbitron may have had in this.

Diary programming vs. Meter programming—.

Big differences in how programmers took/take chances on music.

No doubt the change to meter methodology a dozen or so years ago in the nation’s top 48 market exacted a toll on everyone’s appetite to play new music, as well as air artist interviews and special features, syndicated shows, concerts, etc. In retrospect, the timing couldn’t have been worse.

Radio used to be a reflector based on record sales. Sinatra got played right next to the Beatles and the Monkees simply because of what people were buying. Sales represent a listeners commitment. It was a cheap form of market research for radio. Why can’t that work today flavored with engaging DJs to accompany the listener on a trek through the charts? Could radio people be over-thinking this stuff? On the other side, live streaming music is stupid cheap to do with today’s technology. That could make music more timely. In the ’60s it was not uncommon for a song to have been written within a few weeks or even days of when it hit the stores and airwaves. Today it’s often a year or more. I think that’s a lot of why people were more engaged with new music.

Fred, another couple of excellent blogs.

The one thing no one seems to mention is what I think started it ALL. When R&R cut the small markets. They were the ones who could AFFORD to take chances with new music due to the lack of radio station choices in their market. Use it or lose it kind of shows, guys who LIVE IN THEIR MARKET taking requests nightly with their finger on the pulse of their market. Then, what made it worse, consolidation. That’s when the “Group PD” thing really gained traction. Then, you have one guy adding songs to 40-50 markets a week. Usually these group PD’s come from markets that don’t take chances, as the competition is fierce. How can they be expected to go SO FAR from what they know from their experience, works? What they (the major market guys who talked themselves into our jobs) lost when they took it all, was their test markets. They lost the PD’s who really knew how to do it in their market and succeed. The PD’s who were reporting the spins to R&R that made them take the chance on the songs.

I think radio forgets we don’t do it all. The record companies have blame in this as well. A fact well stated in your blogs. The talent promoters have some of the blame too.

I will go to my grave saying there is always good music available in every format. Maybe not as much as we think there should be, but it’s there. You just have to want to find it. And work for a company that will let you play it.

Good points all, Tammie. Pre-1996, most radio companies were limited to 7 FMs – period. And most of them weren’t especially “top down.” That led to independent decision-making on music – some of it magical, some of it good, and some of it self-indulgent and ineffective. As companies grew, that penchant to have a firmer handle on what everyone was doing became more and more the industry standard. It’s a different world today. Thanks for chiming in on this one.

I never read your comments, Tammie, that I don’t find myself thinking, “Can we elect this girl the next President of the NAB?” Excellent observations. Is anyone in Radioland listening?

FM radio happened in the late 60s and early 70s because corporations and station owners didn’t know WHAT to do with it so they gave it over to young freaks who knew how to speak to their tribe. It succeeded by ignoring the tightly formatted rules of the day. The drum beat was spread by word of mouth. That’s probably how it might happen again if corporate owners just gave over operations at under-performing signals to young minds who could combine stations with other media platforms to reel in younguns’ who’d stopped listening to radio. Leave them totally alone for 5 years and see what happens. A hands-off Manhattan Project or Moonshot for radio. Not likely but I like imagining it.

It would make a great Netflix mini-series, that’s for sure.

You are right that conditions happened organically that allowed for progressive rock radio to happen. You never know, right?

I don’t know if this would work, Paul, but man, I wish someone would give it a try. We already have a long list of “what won’t work.”

You know. There’s plenty of blame to go around. Various strains of ignorance, fear and loathing. I’m not there. There is probably some truth in all of it. We’re all waiting for the next big thing. Like public radio is waiting for the next Garrison Keillor and Click and Clack. I gotta ask. Do you think the problem is the music? New music to my ear sounds overcooked, overhooked, lyrically bankrupt and melodically nowhere, I could go on. If you analyze it, it doesn’t stand up to the classic stuff. I believe people are tired of the same old mish-mashed musical memes and we all want great artists singing great songs. The walls are grey. Everything is so gloomy. We all want a break. Everybody can recognize good stuff, from record execs to John and Jane Doe listener. Even the big mouth influencers and tastemakers have to start with better content. I don’t think there is any….for now. Doh. Why do I sound so gloomy?

Lalo, this is one of those rare instances where we disagree. And I’ll tell you why. A part of Gioia’s essay I agree with is that the labels (first) and radio (second) are so intent on looking for music that fits a modl/sound/formaat/genre they miss some of what is truly out there. I believe the new music you/we hear is a product of the homogeneity. There’s better stuff out there, but it’s not getting surfaced because it doesn’t sound like everything else. So, maybe we’re actually saying the same thing. Good to hear from you, as always. And cheer up!

The research behind that article was well, suspect. While there are more gold based stations than current focused ones on Sirius, there are plenty of places to hear new music. Is there less new music being listened to, or just more old music? As more older people are using Spotify, the percentage of old music is growing, so a more valuable metric would be raw streaming numbers, not percentages. Also, the past two years aren’t representative, as comparatively little new music has been released. Most artists make very little money on streaming, so without the opportunity to tour and monetize an album, most held their new material back.

These conversations about radio and new music are fun, but when one person is programming a format for their entire group and that person is beholden to the major labels for almost all of their promotion money, there isn’t enough well, bandwidth for much more than the safest, high priority artists.

Between abandoning 12-34s and hub and spoke programming, radio has abdicated new music to other media and I’m not sure if they tried to reclaim it if many would come back to find it. It may be that new music and the ways to discover it have become so stratified that the radio as new music destination ship has sailed.

You may be right, of course. The post didn’t paint the strategy as a slam dunk. It’s not. As you suggest, a lot of mistakes have been made along the way that have put us in the box we’re in.

I’m counting on one thing – that if radio actually leaned into new music (again), the labels would reciprocate. That may be naive, and it might run against the grain of the current strategy. But as much of a mess radio has made, the labels have made it worse.

We’re probably playing with Monopoly money anyway, Bob, but I will believe that in spite of everything, radio can still move the needle better than any other platform. Thanks, as always.

Concerning the mention of When We Were Young, I’d argue that radio didn’t really play a lot of those bands much in the first place–even though it should’ve. Some of the acts did at least fairly well with commercial Alt/Modern Rock (or with mainstream Rock), others had better success at CHR, but plenty of them never got a lot of airplay anywhere.

Appreciate it, Eric.

For my radio show and podcast I listen to 100 titles or more every week. New music is the most disappointing experience. Lots of copy cat lame sounding efforts but some new things shine and I play them along with my focus on everything ever recorded. Every era needs an idol to light the path. It will happen

My first thought at the TS chart showing a drop from 39 percent to 25 since 2014 was that’s not TOO bad, if you consider the explosion of outlets where new music can be discovered. (I wonder what percentage of TV audience “the big three” TV networks you and I grew up with–probably once in the 90’s–have now?)

My next thought was more discouraging. Many youtube and TikTok stars have 10s of millions–or more–of views and fans and followers. It would be easy enough for a station to feature those artists with the highest followings–but why would any of those fans tune into that station? They wouldn’t be “discovering” new music, they would just find a station playing the same music they already “discovered.” It’s still radio being the “follower” rather than the leader. (Though I personally think it’s worth trying.)

I think Chris Anderson’s comment might sum up what radio’s up against best: “Up until now, the focus has been on dozens of markets of millions, instead of millions of markets of dozens.”

And yet, like you, Fred, I still have hope for radio that “the next big thing” is out there, and that it will happen when we’re not looking for it. Can you say, “The Wordles”?

Has it been 37 years since we started your idea on the air near the cow pasture? Doesn’t seem possible. But, you’re right, Boss. Not enough emphasis is given to mass expose anymore, and every big radio group has their fragment of stations and offerings, none aiming to mass market. Some time, maybe, there could be a retool of radio for a larger audience. Something to ponder, maybe?

Hard to believe, right? Thanks for weighing in on this one.

And meanwhile, two songs from the latest Disney animated film are in the top 10 of the Hot 100 and barely any radio stations are playing them. Just like the cast of “Glee” beat the Beatles’ record for most Hot 100 singles with no radio airplay at all. And Kpop was ignored by radio for a long time until they couldn’t ignore it. Why doesn’t CHR play only the hits that fill their narrow template? Why won’t radio talk about “Bruno?”

Good question, Mark.

I speak from the listener side on a long perspective going back to the ’60s. From where I sit, commercial AM/FM has been willing to experiment only on odd occasions and usually when nothing else seems to be working. Progressive free-form FM radio where the DJs were just as much artist as the music they played spawned in an environment that was largely ignored — even disdained — by the radio brahmins of the time. And once the latter discovered its success, they killed it. Not intentionally perhaps, but in using the same thinking they were on AM, FM became more clone than dynamic. Are there any free form commercial radio stations in existence today? I can name a couple in NY and VT — one in Woodstock, the other in Manchester. Otherwise, it’s bland formula everywhere. So where is the true experimenting taking place? Public radio is utilizing HD Radio in creative ways to serve diverse audiences — news/talk/docs, classical, jazz, indie/new/local music — stuff you never hear on commercial radio despite its evident success. Instead, there’s rock sliced and diced into “formats”, country, angry white man talk radio (where’s the diversity there?), sports talk and what else? The FCC has given them more and more stations and they program the same dull stuff because the ratings appear to tell them to do so. So, where do I go besides public radio? When I was younger, it was shortwave to hear somethings new and different. Not it’s internet radio where I have access to over 60,000 stations around the world. Imagination and fearlessness is what’s lacking. Talent — real talent, not the talk charlatans lionized as such — too, is what’s missing on many levels in commercial radio. Maybe if their stations weren’t so leveraged financially? Apologies for the rant. It’ll probably get deleted anyway.

It bummed me out reading this Fred, to have to leave my PD hat on the table and reluctantly take out the GM one. Hate that.

When staring at the Green/Red ‘Long Tail’ graphic I couldn’t help but think, “How would I pay for all, or mostly, small audience’d niche stations?” That’s sort of what that ‘tail’ looks like; little stations. Hopefully all great sounding stations, but with normal size station costs (fixed ones you just can’t cut below).

I guess with a cluster you could try just one as we’ve all been suggesting, but is that enough to make any difference. Doesn’t seem like it. Hard thing to reconcile with, but maybe we’re holding onto trains when airplanes take the passengers.

The math just seems off.

I’m not sure if we’ll ever get the dollars and the programming in sync again unless the staff makes peanuts, they let up on music rights payments, and somehow real estate, towers, equipment and electricity etc. drop by 50%.

A thought, albeit a really crappy one.

The model is becoming increasingly untenable, Pat. I think that’s what it’s coming down to. I share your pain.