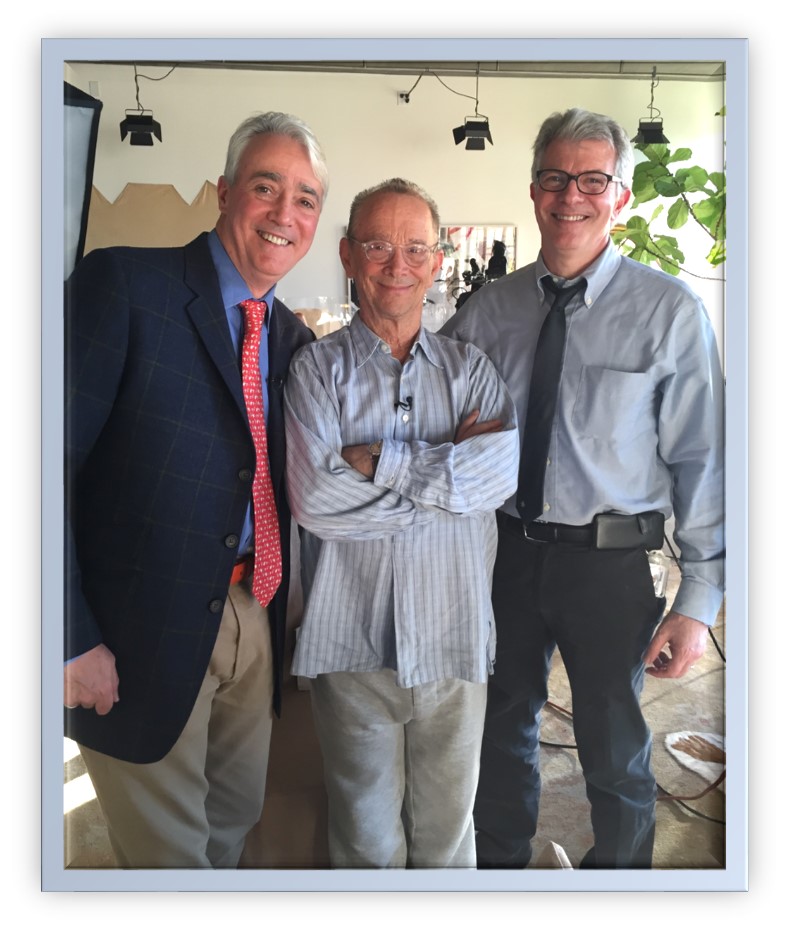

Over the years, we’ve met and had the honor of working with some amazingly talented people. One of the standouts is Jay Kernis, who was with NPR for nearly 21 years. We met Jay when he served as their SVP/Programming in the 2000s. In that capacity, he oversaw the creation, acquisition, and growth of all NPR programming, along with its HD radio, satellite radio, and digital assets. Jay had an amazing job and approached it with a sense of class, control, expertise, and empathy.

Jay has also spent many years in television, always in high-profile positions. He produced for Mike Wallace and Lesley Stahl at 60 Minutes, and in recent years, produced for both CNN and NBC News.

These days, Jay has an amazing gig. He’s back in TV, serving as producer for CBS News’ Sunday Morning, a program that has become a weekend ritual for many of us.

Over the years – especially at NPR – we watched Jay engage with talent at the highest levels, helping bring out their best work. Whether you’re in news, sports, or even music radio, Jay’s view of the media world will give you something to think about, and help you prep for that next story, bit, or interview. He has an amazing ear and eye for what works, which is why we asked him to write a “Guest List” feature:

“5 Things I’ve Learned In Television That (Public) Radio Should Know”

Sure, there’s a lot to criticize about TV and television news. But TV still can have a huge impact and gets a lot right.

Here are some things I have learned that may be worth a mention:

1. Tell Me a Story

When Don Hewitt was asked why 60 Minutes was such a great success, he always said, “It’s four words every kid knows: tell me a story.”

Stories involve compelling characters in a dramatic situation that lots of people will care about.

An issue is not a story. An event is not a story. Neither is a successful business or an organization celebrating its 75th birthday. But reporting on a remarkable person involved in a conflict or wanting to achieve a goal or surpassing roadblocks may be a way to illuminate an issue or event.

Stories have a beginning, middle and end, and along the way, the audience wants to know what will happen next. Take them on the trip with simple, but colorful, language that helps the listener make sense of all the information that is being presented. Take the time to explain things.

Stories need to be focused on what is essential and what is memorable.

2. Passing the “Why Should I Care? Test”

There still seems to be an assumption that the audience cares about certain “Important” subjects — the environment, immigration, the endless

Mideast peace process. It’s as if producers think that the subject alone will keep the audience tuned in, due to some mental picture of who’s out there and what they like.

Sometimes it’s immediately evident why a story is being aired. At other times, a reporter needs to explain why the story is worthy of our time and attention.

3. Present Something Happening

TV can be wonderful when we show the audience something that occurred, rather than arriving later and asking: what happened? The cameras were there to capture people doing something new, important or unusual. Take us places where we can see characters in action.

TV also does “live” very well. Maybe public radio networks and stations should have microphones at more live events.

4. Who Are These People?

Characters in stories are often introduced very quickly and due to time constraints, without enough background to understand why they are telling the part of the story that they’re involved with. Tell us more about these characters, whether it’s about their backgrounds, behaviors or beliefs.

Characters in stories many times return later in a story and the correspondent expects us to remember who they were. Tell us again.

5. How to Treat On-Air Talent

In the socialist experiment that is public radio, everyone — producers, hosts, correspondents — is sort of treated equally. The culture, as I remember it, involved not treating on-air people like stars. Not enough special attention is paid. I’ve worked and visited places where managers openly resent on-air performers.

In TV, the person in the anchor chair is usually treated as if he/she sits on a throne and receives divine wisdom.

But I do think there is a middle ground. Hosts and correspondents do something very special every day or week: they gain the audience’s trust, speak with authority, develop on-air personalities that make people want to return again and again, and have to get it right every time. They walk the tightrope while most of us are on the ground, waving, nodding, smiling and holding the net in case they fall.

I have found that the more you treat on-air personalities with respect, the more you demonstrate that you have their backs, the more you show your appreciation for the work they do — the better they perform.

Fred note: The original post stated that Jay worked for NPR for nearly 14 years. I was never great at math, added up his resume items, and amended the post to read “nearly 21 years.”

More Guest Lists

- Matthew Lasar: 6 Pivotal Moments in the Internet Radio Era

- Jeff Smulyan: 5 Things Every Radio Professional Should Know About NextRadio

- Sheri Lynch: The Top 5 Radio Topics That Get The Phones Ringing

- Luke Bouma: 6 Things Every Radio Broadcaster Should Know About Cord Cutting

- Greg St. James: 5 Lessons Radio Can Learn From C-SPAN

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

Leave a Reply