Over a century ago, anti-monopolist Lizzie Maggie created a game she hoped would educate the world about the economic evils of land ownership as it was structured in 1903.

She may not have exactly accomplished that goal, but she did end up dreaming up perhaps the most popular board game of all time, Monopoly.

Originally called “The Landlord’s Game” because the goal was to buy up all the properties and destroy your opponents, the name was later changed to “Monopoly,” and it was purchased by Parker Brothers for the tidy sum of $500 in the early 1930’s.

Its current owner, Hasbro, bought the king of board games in 1991, and began to create and license various versions, starting with a San Diego edition.

We’ve all played the game, developed our strategies, and at times our own family rules. Despite the variations, however, there are certain “givens” that we all follow – passing “GO” and collecting $200, going directly to “Jail,” and obeying whatever it says on those unpredictable “Chance” and “Community Chest” cards.

Another emotion we all share about “Monopoly” is the “meh” feeling we get when we land on one of the utilities, “Electric Company” or “Water Works.” (A modern-day version would be landing on “Cable Company.” Ugh.)

We know nothing very exciting happens when we land on a utility. We can’t build and develop them. The price never changes – its $75 (or 10% of the roll of them idce) if we own one, double that if we own both of them.

Lizzie Maggie knew what she was doing because utilities unspectacularly supply a straight-forward, expected service that doesn’t stimulate or enchant. Unlike the ritzy Boardwalk or Park Place or even scarfing up all four railroads, the utilities are what they are – stable services we expect to be there when we flip the light switch or turn on the faucet.

So, why have so many radio stations reduced themselves to broadcast utilities today?

That’s the question I couldn’t get out of my head when I read “How to build brands that resonate” by Nielsen’s chief marketing and communications officer, Jamie Moldafsky.

That’s the question I couldn’t get out of my head when I read “How to build brands that resonate” by Nielsen’s chief marketing and communications officer, Jamie Moldafsky.

While not necessarily ground-breaking or revelatory, Moldafsky’s article covers the basics and does it well. Given the exponential explosion of choice in the media marketplace, she reminds us of the imperative of creating “a compelling brand narrative that unifies (a brand’s) organization, resonates with customers and the market, and helps differentiate (the brand) internally and externally across all touchpoints.”

Now, that’s not so hard, is it? But a look across today’s radio broadcasting landscape today reveals fewer and fewer are making Moldafsky’s definition of a viable brand a reality. With each passing year, once great brands are sold, erode, or collapse altogether.

Given the growth of able, well-heeled competitors, radio brands need more than a simple positioning statement that defines what they do. As she reminds us, “In a complex and dynamic marketplace, it is important for companies to be clear about their values and purpose as well as the unique product or service they bring to their audiences – including what they stand for, what they offer, and how they deliver.”

complex and dynamic marketplace, it is important for companies to be clear about their values and purpose as well as the unique product or service they bring to their audiences – including what they stand for, what they offer, and how they deliver.”

So, here’s the question:

“What does your station’s brand stand for?”

And don’t tell me you’re Greenville-Spartanburg’s Country Station.

Your format is not a brand.

That’s because if I want to hear country music while I’m in “The Upstate,” I can find you on the radio dial. Or I can access an amazing playlist of country on YouTube, Spotify, my Sonos system, Amazon Music, Apple Music, Pandora, CMT, the Country Channel, any number of SiriusXM channels, 25 different free channels on AccuRadio, on apps like iHeart and Audacy, and scores of other sources (not to mention my personal collection).

That’s because if I want to hear country music while I’m in “The Upstate,” I can find you on the radio dial. Or I can access an amazing playlist of country on YouTube, Spotify, my Sonos system, Amazon Music, Apple Music, Pandora, CMT, the Country Channel, any number of SiriusXM channels, 25 different free channels on AccuRadio, on apps like iHeart and Audacy, and scores of other sources (not to mention my personal collection).

In other words, country music is a utility – like “Water Works.” It has been commoditized. It is ubiquitous. I can listen to whatever country song I like, wherever I like, and whenever I like on my iPhone. And I can watch a corresponding video on YouTube if I prefer, by the original artist, umpteen “cover” versions, as well as live performances from around the world.

So, what is it about your country station in your market that provides a unique experience? I’ll be taking on that challenge next year when I take the stage at CRS, the world-famous Country Radio Seminar set for March 13-15, appropriately in Nashville.

So, what is it about your country station in your market that provides a unique experience? I’ll be taking on that challenge next year when I take the stage at CRS, the world-famous Country Radio Seminar set for March 13-15, appropriately in Nashville.

It’s being billed as a FRED TALKS, and you can bet among other topics, I will be addressing this issue of creating, building and sustaining strong radio brands in an uneasy atmosphere of belt-tightening and layoffs.

building and sustaining strong radio brands in an uneasy atmosphere of belt-tightening and layoffs.

Moldafsky may frustrate those of you who read her branding paper because she emphasizes the need for ongoing research and marketing support, two resources in short supply at most radio stations. And even when some budget is cut loose for a market research study, it is usually confined to testing the music, checking images, and measuring the vital signs like cume and P1 status.

Rarely does it delve into the issues Nielsen’s marketing maven suggests – ascertaining what is it about your brand that matters to your key constituencies – audiences, advertisers, and communities.

Moldafsky doesn’t gloss over a key group that matters more and more – the staff. She emphasizes the need to communicate a radio station’s brand essence and purpose to employees to ensure they’re “in-line with brand messaging (because) consumer experience remains a powerful brand builder.”

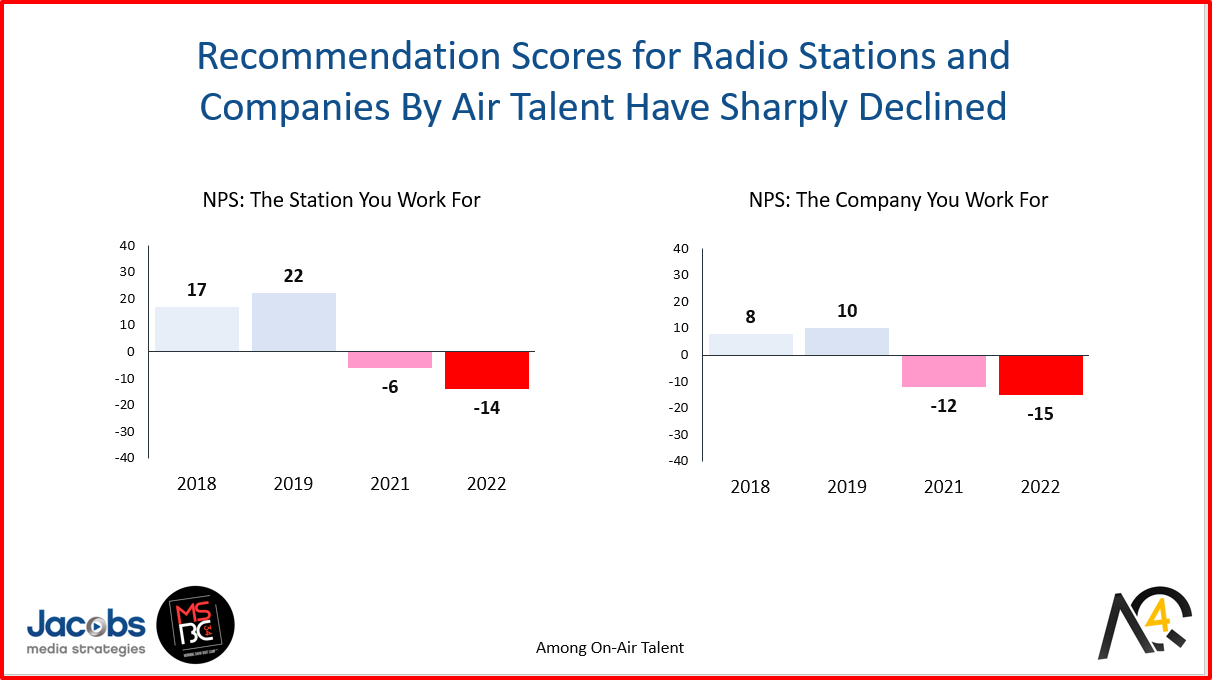

On that note, the repercussions of the pandemic appear to have stimulated employees from all industries – especially younger ones – to assess their companies’ values and ability to compete. That may be happening more and more in radio, too, based on eroding opinions of how air talent rate their stations and parent corporations. We’ve tracked this over time in AQ4, our study of talent in the U.S. The progressively lower trendline in Net Promoter Scores is unmistakable, especially following COVID:

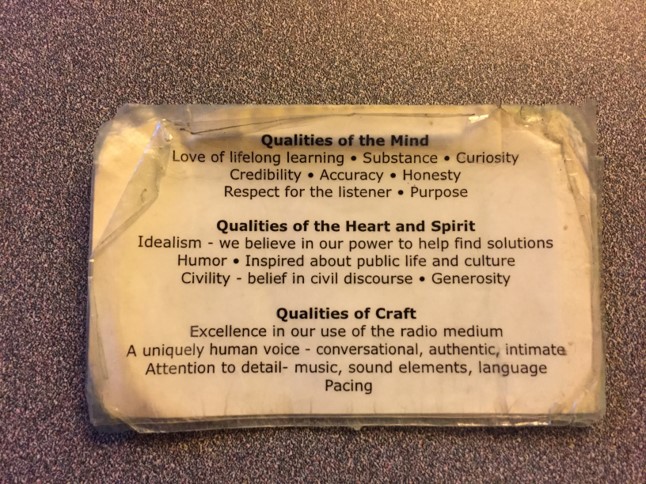

Moldafsky’s article reminded me how public radio news stations (and those that play music, too) have maintained their uniqueness thanks to the spadework done by the medium’s matriarchs and patriarchs back in the 1970’s.

While public radio stations and their networks have changed in many ways over the decades, their adherence to these seminal “core values” has kept the platform vital and relevant, even throughout the Digital Revolution. The values that launched public radio a half century ago still hold up especially well today.

Back then, programmers carried around “Core Values Cards” (pictured above) laminated and carried by the format’s practitioners. There’s never been any doubt what these radio stations stand for. These values are still meaningful and resonant today.

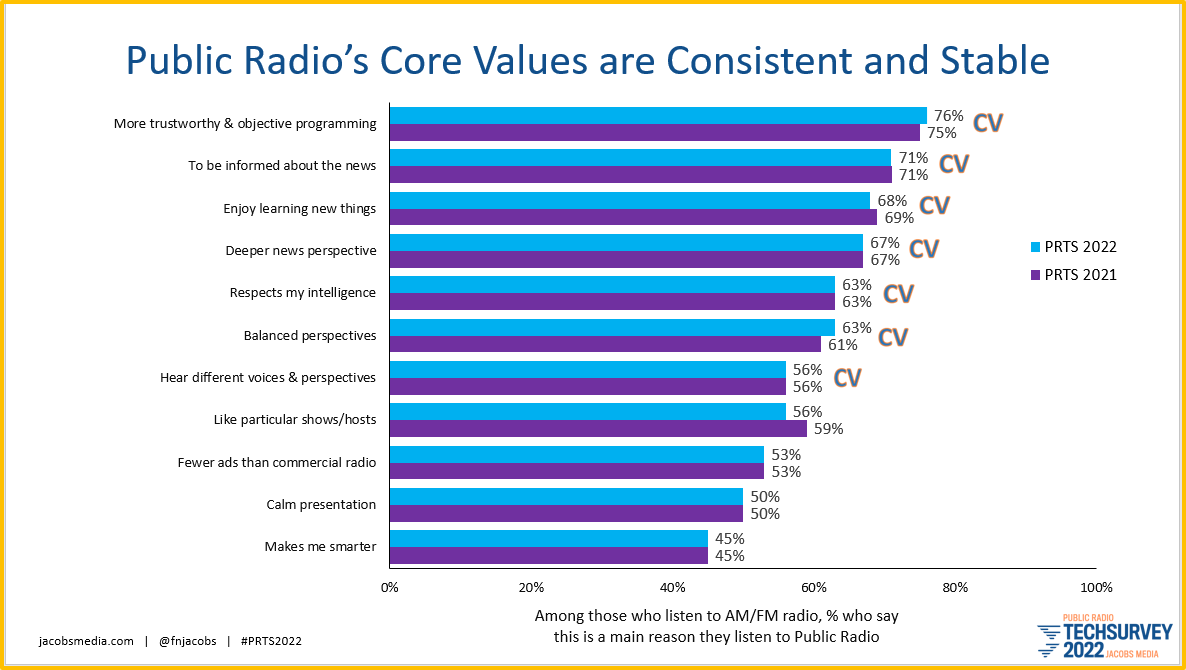

In PRTS, we ask the “trackable” question, “Why public radio?” to the format’s core users. And as you can see by the year over year comparisons, these top values (designated by “CV”) are sacrosanct, immutable, and as strong as ever, even through economic and funding crises, a global pandemic, and the disruptive emergence of the Internet.

While most radio stations no longer market themselves off their own air, Moldafsky suggests it may be more important for all involved to “be the brand” in ways that bring their values and “proof points” to light.

What does that look like?

It means that in everything a station does – its production and imaging, its events and meetups, its airstaff and what they say, its account reps and what they will (and will not) sell, the mobile app and digital assets, where it shows up, and the community and public affairs events it chooses to get involved with – it reflects and exudes that brand essence.

It means that in everything a station does – its production and imaging, its events and meetups, its airstaff and what they say, its account reps and what they will (and will not) sell, the mobile app and digital assets, where it shows up, and the community and public affairs events it chooses to get involved with – it reflects and exudes that brand essence.

Whether you stand with veterans, first responders, or your local children’s hospital, your brand should be in-sync with what your listeners and your community care about. Plus, I can tell you as a former PD, it’s makes your job and decision-making easier when you know what your brand stands for. Sure there are quandaries, conundrums, and issues where you wring your hands. There always are. But your process is more focused and streamlined when your station is “on brand.”

When you have a viable brand in place you support in myriad ways, your station takes on a narrative – its life story. Plus or minus for great brands, the audience knows your story, how you started, how you got here, and why you still matter. Stations without a story end up living from contest to contest or event to event, rather than building a brand engine that well get them through the worst of times when every medium is tested.

how you started, how you got here, and why you still matter. Stations without a story end up living from contest to contest or event to event, rather than building a brand engine that well get them through the worst of times when every medium is tested.

Public radio PDs do more than carry around plastic wallet cards. They all speak from the same “brand bibles.” There’s never a systemic debate about the medium’s values and what they mean. Everybody knows. They devote their resources to building their brands, rather than debating them.

And the net effect is “trickle-down marketing.” When a station is true to its brand essence, not only do its employees “get it,” but the audience does, too. As Moldafsky affirms, “I’ve found the consumers feel it, which further cements their trust in the brand.”

With the holidays rapidly approaching, there’s a prime opportunity for PDs and market managers to take stock of their stations and the cluster. Is the portfolio a bunch of bland utilities, presenting competent but unremarkable playlists of music, day in and day out?

Or are stations living, breathing brands, reflecting a culture and real values that matter?

Radio station that are mere utilities will not last or generate consistent profits in this atmosphere. The competition is too good, too vast, and too researched and well-marketed. It is also deeper-pocketed. Radio brands that hope to remain in the game will have to do it with unique programming, marketing, and yes, branding.

The busier the marketplace, the more brands that matter in their communities stand out and deliver.

Meantime, will the last great radio station brand please remember to turn the lights out?

Jamie Moldafsky’s article originally was published in Forbes.

- I Read The (Local) News Today, Oh Boy! - April 15, 2025

- Radio, Now What? - April 14, 2025

- The Hazards Of Duke - April 11, 2025

Great piece. Loved it all except your last line about turning off the light?

Excellent analogy. Similar to Oriental, Vermont and Connecticut Avenues (light blues) being efficiently priced right in a very strategic location on the board.

The answer to “What is branding?” is perhaps best illustrated by examples, and you provide NPR as a fine one, Fred. With h/t to Justice Potter Stewart, I know it when I hear it. When you’re at CRS next March, you might offer the audience the excellent example of WBCM, “Radio Bristol, the Birthplace of Country Music.” Best programming I’ve ever heard in that genre, what a brand! Much can be learned simply by paying attention.

One can also observe examples of brand destruction. The waste of KJAZ’s brand when sold in the ’90s by its capricious owner is seared in my memory. And just days ago we saw that WRNR, “Radio Annapolis,” is now on the chopping block and the blade has descended. Nothing personal, it’s just business–but wanton destruction nonetheless.

A couple of fairly similar, nearby examples that I’d suggest to complement WBCM are WDVX (Clinton, Tenn.) and WNCW (Spindale, N.C.).

Appreciate this, John.

Moldafsky suggests to be the brand:

OK then…

Presenting:

98.5–The Brand.

—Win a grand on The Brand

—You favorite bands play on The Brand

—Brand new music on The Brand

—Sign up and become a Brand Loyalty member

We also have an alternative format available:

Brand X.

Marty Bender

Worst Consultant Ever

Just remember how they “branded” the cowpokes in “Yellowstone”.

Maybe we should sign it on in Brand Rapids?

Just FYI, the Public Radio station I work for (Tri States Public Radio) is based in Macomb, IL. The birthplace of Lizzie Maggie. There is a original version of the Landlords game displayed at the train station.

https://www.tspr.org/tspr-local/2022-05-10/macomb-celebrates-ties-to-monopoly-with-acquisition-of-historical-artifact