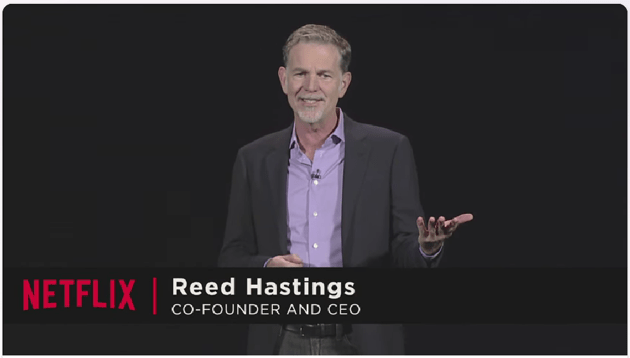

Once upon a time after Netflix transitioned from red envelopes in the mail and DVDs, its streaming platform was a uniquely wonderful feature that propelled them to the top. At CES 2016, its CEO at that time, Reed Hastings, gave an upbeat keynote address. Credited with inventing the term “binge watching,” Hastings was excited about his company’s plan to expand into an even bigger footprint around the globe.

While Netflix has enjoyed massive success over the past decade, its market has become exponentially more crowded. Up against the “+ crowd,” Netflix faces big-time challenges from the likes of Apple, Disney, Paramount, Hulu, and many other formidable competitors, all trying to win share in this massive financial space.

To adjust and adapt, Netflix has shaken up its business model, now offering a lower-priced tier that includes commercials. These kinds of moves are designed to help Netflix retain its leadership position and growing the audience by appealing to segments that are less inclined to shell out $10 a more a month to watch romcoms, docs, movies, and TV series. In other words, it’s “Netflix for people who don’t have Netflix.” And in the short run at least, it appears to be working.

growing the audience by appealing to segments that are less inclined to shell out $10 a more a month to watch romcoms, docs, movies, and TV series. In other words, it’s “Netflix for people who don’t have Netflix.” And in the short run at least, it appears to be working.

But there’s more to competitive differentiation than shaking up the business model – adding commercials, adjusting the platform’s pricing structure, and even cracking down on shared user names and passwords. When you have as many subscribers as Netflix does, these types of modifications can be difference makers on the balance sheet. But none are content plays – changing the shape and scope of Netflix programming.

Until now.

Now, Netflix is making a unique content play in an attempt to set the platform apart.

To this point, most of Netflix’s effort – and massive budgets – have been earmarked to new, cutting-edge programming. Shows like Tiger King and Squid Game have generated enormous buzz in recent years. Films like Scorcese’s The Irishman have been critically acclaimed, vaulting Netflix into the rarified air of big award wins. And the brand has also experimented with live programming, including Chris Rock’s comedy special back in 2022.

Now, it’s all about “nostalgia,” and it will sound very familiar to many radio programmers. In a story published in AV Club last week, writer Sam Barsanti reports Netflix has been aggregating a new category of films from a variety of studios. What do they have in common?

They are all from 1974.

So, what do 14 movies that are exactly a half century old have to do with Netflix’s new content strategy? Barsanti says the streaming giant has been watching which movies from that year are for sale, and has aggregated them to put together a special feature category.

aggregated them to put together a special feature category.

Radio programmers might call this a programming stunt – featuring hit movies from one great year. In fact, many of Jacobs Media clients might brand the feature as “Classic Rewind” or “Years in Your Ears.” Netflix is going in a slightly different direction, referring to this collection from the seventies as “Milestone Movies.”

So while Netflix programmers aren’t using the “C-word” to describe films like Chinatown, Blazing Saddles, The Conversation, The Great Gatsby, and The Parallax View, these are all classic films. Perhaps they’re avoiding the obvious reference to TCM – or Turner Classic Movie, but it’s obvious where they’re going.

To use a little radio math here, if you were 16 in 1974, you’re 66 years-young today. While that’s not a prime demographic for television, it is about subscribership for channels like Netflix.

But perhaps the bigger bet is that young people are going to discover these classics…er milestones…soon enough just as they have Led Zeppelin, Queen, AC/DC, and the Doors. Many of these films are timeless, and they’re probably preferable to watching yet other CGI-loaded superhero movie.

And for Netflix, they are chasing this blast-from-the-past strategy like Rambo on a mission. In the next few months, AV Deli tells us similar specials focused on 1975, 1985, 1995, and 2005 are all in the works. It’s not hard to tell where this is headed.

(Interestingly, Max and Paramount+ – who have these old relics collecting dust in a vault somewhere – aren’t interested in chasing memories. At least for now.)

In media and pop culture, nostalgia has become a go-to strategy for many brands trying to jumpstart their way to success. Lord knows we’ve seen it work in radio, thanks to formats like Classic Rock, and others that have generated audience ratings and revenues by dipping back into the past.

In fact, it’s played a major role in Alternative’s comeback during the past couple years. And while it has come at the expenses of new music exposure, ratings are ratings.

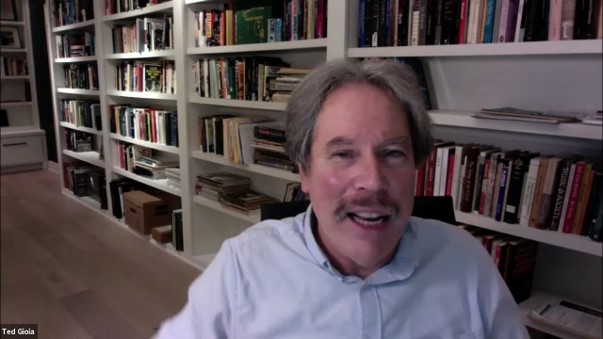

Until, that is, an entire sector is impacted by a rush to gold in the world of music. So suggests Ted Gioia, renowned music analyst and critic who I’ve featured on this blog before.

Ted’s latest premise is in his new article, “Why Is Music Journalism Collapsing,” in which he takes a look at the the recent “demotion” (as he calls it) of Pitchfork, a bold voice for music – especially new music – for the past quarter century.

For music lovers and those who enjoy living on the cutting edge of what’s new and what’s next, Pitchfork is essential journalism. And now, it’s being folded into GQ, another holding in the Conde Nast family. Layoffs are one thing. Becoming a part of a men’s fashion magazine is downright insulting.

But it’s happening.

But it’s happening.

The fate of Pitchfork isn’t an anomaly. Ted refers to the recent housecleaning at Bandcamp which lost roughly half its employees to staff cuts.

While it may have nothing to do with music, Sports Illustrated was decimated last week, bidding adieu to 450 of its staff members, effectively terminating a magazine that’s been around since Mickey Mantle roamed centerfield for the Yankees.

New York Times columnist Ezra Klein suggests these strategic cutbacks may be even more devasting. Listing example after example, Klein sees this disturbing trend as a commentary on the not-so-slow death of journalism. He makes his case in “I Am Going to Miss Pitchfork but That’s Only Half the Problem” published last weekend.

To Ted Gioia, the signs point to changes in the music economy, impacting more than Pitchfork. He points to recent staff reductions at Universal Music, YouTube, SoundCloud, Spotify, Tidal, and Amazon Music has proof positive that brands that depend on music consumption are likely hurting.

He points the finger at the rush to nostalgia.

And Gioia notes that when a brand – or platform – becomes dependent on old music, they’re betting their future on passive consumers – fans who would rather hear the oldies and classics.

He says the hundreds of millions being invested into purchasing entire artist catalogs of gold music only reinforces the emphasis away from new releases.

And Ted also says that algorithms are now trained to push “streamies” to AI-generated music – thus, zero royalties being incurred, and less new music being sampled and heard.

He sums up the state of play for Pitchfork and other brands that are current and recurrent-dependent:

“If people don’t listen to new music, they don’t need music reviews.”

They also aren’t going to listen to radio stations that pin their hopes on playing the new stuff, at least not without enough mass audience to work on the commercial airwaves. (Are you paying attention public radio?)

In his analysis, Gioia essentially writes off the record labels and streaming platforms in this growing crisis. In fact, he asserts, they’ll “be the last to figure it out.”

Instead, he suggests writers and performers adapt their business model by going direct-to-consumer. That’s right, creating connections between themselves and fans, the people who most appreciate hearing something new, rather than “musical milestones” 24/7.

Interestingly, Gioia only mentions one of the new music industry’s key co-conspirators just once. Of course, I’m talking about radio. He briefly laments the fact radio once also depended on new music in order to survive and thrive. And then moved on.

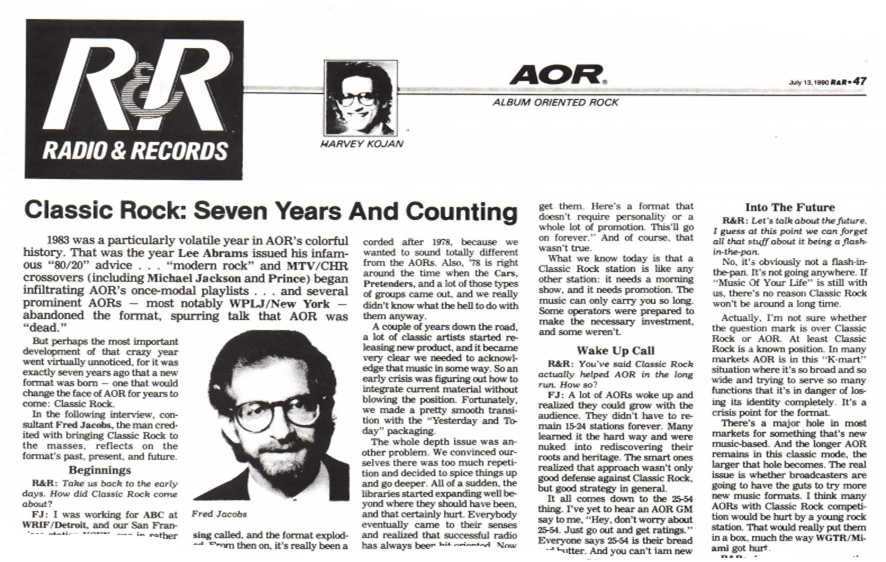

I’ve got nothing against nostalgia. Speaking of Classic Rock specifically, you’ll never hear me badmouth it. After all, it paid for two kids’ braces, Bar and Bat Mitzvahs, and college educations. It also served as a turbo-charged V8 engine for Jacobs Media for the first 20 years of its existence.

I’ve got nothing against nostalgia. Speaking of Classic Rock specifically, you’ll never hear me badmouth it. After all, it paid for two kids’ braces, Bar and Bat Mitzvahs, and college educations. It also served as a turbo-charged V8 engine for Jacobs Media for the first 20 years of its existence.

But it was never designed to replace or even usurp the power and impact of radio’s new music adventures – or what the record companies were investing in. I’ve heard people say, “Classic Rock is a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there.”

I get that. But for millions of fans, nostalgic music is the path and the destination. That’s their comfort zones, and who are we to question those tastes. That said, nostalgia – in the form of Classic Rock, ’90s ALT, and the other iterations of gold-based radio and genres should never have been the main tributaries of the radio industry, even though sometimes it seems that’s exactly how the industry has devolved.

Last time I checked, broadcast radio – especially on the commercial side of the street – is experiencing much of the same economic speed bumps both the new music and journalism sectors are facing. For many stations and the companies that own them, it’s not working – certainly, not like it once did.

And its traditional role in introducing new bands, their singles and their albums, has often been underplayed by the labels. In the streaming era, radio’s contributions have been all but forgotten, especially as an organization like Sound Exchange make the illogical case it has had little do with the success of musicians, their music, and their record companies. Talk about revisionist history.

Fast-forward to today, and there are questions that need answering.

Is radio part of the problem, and could it be part of the solution? Some readers of this blog will no doubt declare that radio is on life support, its ship has sailed, and that it no longer has a role to play in this complicated play.

I’m not one of them, especially given that broadcasters should be thinking in terms of “What else?” as they survey the wreckage and attempt to recast a viable content strategy moving forward. Companies that once called themselves broadcasters will have to do more than build websites, create podcasts, throw events, and design SEO campaigns in order to work their way out of this mess.

Content is still king. And genuinely new content is the stuff the companies and brands are made up of.

Netflix may get away with their movie gold mining in the short run. But over the long haul, it will need fresh new video content in order to retain its pole position.

At least they won’t be sending out those new movies in red envelopes to remind us of the “good old days.”

Special thanks to Jeff Rowe, Mark Ramsey, and others who continue to stimulate these conversations. – FJ

- Why Radio PDs Are A Lot Like NBA Coaches - May 8, 2025

- Memo To Radio: We Have Met The Enemy And It Is… - May 7, 2025

- The Guy In The Next Car - May 6, 2025

The Ted Gioia article says one of the problems is “…streaming platforms encouraged passive listening—so people don’t even know the names of songs or artists.”

Isn’t radio is guilty of this as well? I rarely hear DJ’s bother to identify songs they play.

Does nostalgia have a best before date? I’m guessing the next five years or so will tell us as more classic artists pass on.

I already see that artists from the sixties are being left behind with fewer songs being heard and less time spend on obituaries. Martha Reeves is eighty-two and has had a dozen top forty hits, but when is the last time her name or music has come up?

Artists of the seventies will soon be suffering the same fate, I’m sure. Despite having perhaps better brand recognition, can that kid in the Jimi Hendrix tee name five of Jimi’s songs? Same with Dark Side Of The Moon.

Who is buying all that new reissue vinyl? Are those records being played, or do purchasers even own a turntable? Some scary answers, when you look that up.

There’s still gas in the nostalgia tank, but how far we can go is uncertain.

Play The Hits. All Classics Rock.

On a similar note, Netflix made a big programming announcement today: WWE’s Raw will be moving to Netflix a year from now.

https://www.wwe.com/shows/raw/article/raw-netflix-tko-partnership-january-2025

Also, Scott Stuber (Netflix’s film chief) is exiting the company.

https://variety.com/2024/film/news/netflix-scott-stuber-exit-film-future-analysis-1235882609

“And the person who takes over from Stuber will have to decide what role Netflix plans to play in a fast-moving movie business. Will it try to achieve the kind of quality that Stuber aspired to, but never quite pulled off? Or will it leave the prestige pictures to Apple and, to a lesser extent, Amazon and instead focus on making lots of movies for the largest common denominator? One important new reality that any film chief has to contend with is that streamers are no longer being measured purely on how many subscribers they add. They are expected to turn a profit, and lucky for Netflix, it’s the only game in town that can do both at the moment. But that means tightening belts instead of spending freely. Cost cutting is the new rule of the day and as anyone in Hollywood can tell you, that’s a lot less fun.”

That’s huge!

Speaking of classics. I know this is sorta off topic but was “New” Coke an accident or on purpose? And when they brought back the original formula what was it called again? Oh yeah, “Classic”. I wonder why they chose that word and the emotional impact it had on marketing.

I give Netflix credit for thinking of it and your analogy to classic rock weekend formats is spot on. There isn’t much difference.

Music discovery timeline:

—Radio

—Radio and that one guy in high school who somehow knew a lot about cool new music

—Radio and music magazines

—Radio, music magazines, and music television

—Online music sites and Spotify

—Ask your kids

Nailed it.