In thinking about how broadcast radio’s music stations hope to compete with streaming services and satellite radio today, and for years to come, most experts might give you a laundry list of things that need attention.

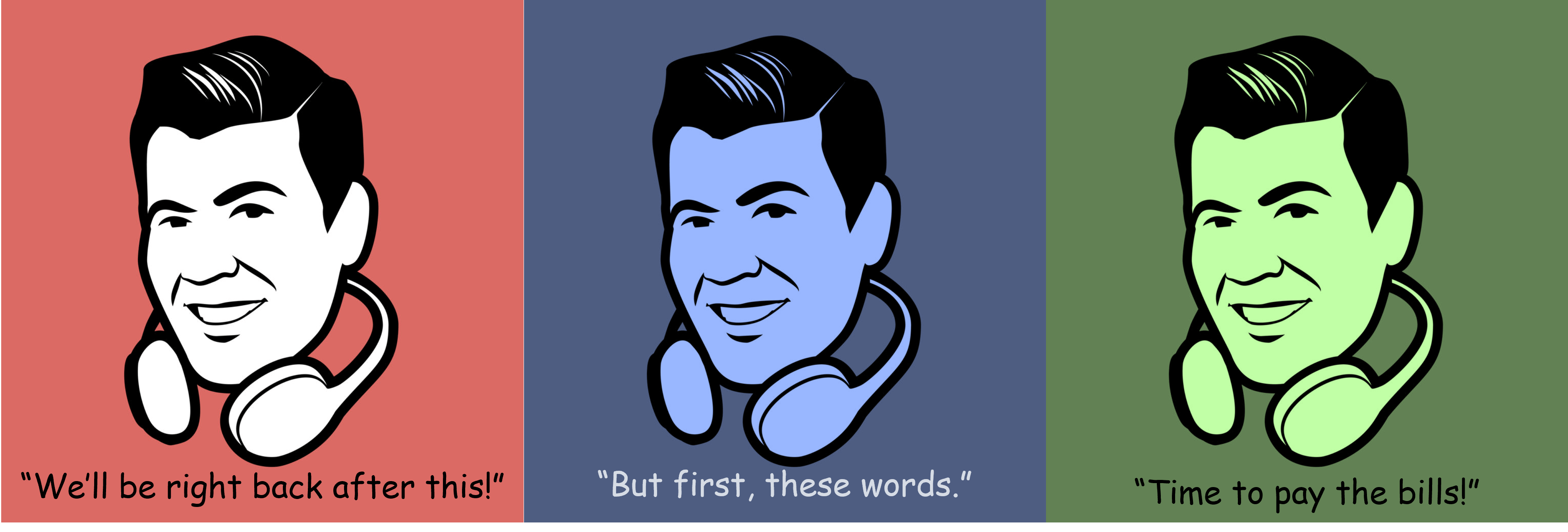

At the top of just about everyone’s list is commercials.

But you don’t need a consultant to give you the down-low. Ask any radio listener (or former listener) and the odds are good she’ll tell you the same thing – the quantity and even quality of the commercials can be a game-changer.

Twenty years ago, radio broadcasters were expanding their commercial inventories in order for stations to meet increasingly aggressive revenue goals. I remember a particular company having an unwritten policy: “There is no commercial load.” In order to make their numbers, commercial capacity simply expanded as necessary, especially at the end of a quarter.

In the pre-streaming, pre-satellite radio era, many stations were able to get away with it. There simply weren’t competitive music services providing a commercial-free environment, other than throwing a half dozen CDs into the changer and pressing “shuffle.”

But over time, consumers became accustomed to non-commercial music environments, and it became “normal” to pay a few bucks a month for the privilege of listening to music sans advertisement.

And when PPM became the ratings methodology law of the land in the biggest markets in the U.S., the accepted practice became cramming an already bloated commercial load into just two stopsets, a policy still in effect all these years later. Whether you’re running bowtie or hourglass clocks, the net effect is like going to fall under the “too many commercials” banner.

commercial load into just two stopsets, a policy still in effect all these years later. Whether you’re running bowtie or hourglass clocks, the net effect is like going to fall under the “too many commercials” banner.

But maybe there’s hope…in the form of an aggressive new legislative model taking shape in of all places, California.

MediaPost’s Publishers Daily ran a story earlier this week that may have touched many a broadcaster’s nerves:

“California Bill Would Use PBS-NPR Model To Support Local Media”

Written by Ray Schultz, the proposed bill – SB911 – comes out of the California Senate. Its sponsor, State Senator Steve Glazer,” says public media’s system of funding is “a model that Americans have long trusted – the non-profit Corporation for Public Broadcasting.”

CPB was established in 1967 as a publicly funded non-profit whose mission is to support public broadcasters financially.

Many commercial broadcasters have long been critical of public media funding. But in reality, a small percentage of money for most public radio stations comes from government tax dollars (yes, CPB). Instead most of it is generated by foundations, audience contributions, and through “underwriting announcements” – public radio’s low-key versions of “commercials.”

government tax dollars (yes, CPB). Instead most of it is generated by foundations, audience contributions, and through “underwriting announcements” – public radio’s low-key versions of “commercials.”

Glazer’s bill seems geared toward smaller California markets – the ones becoming “news deserts,” due to the demise of newspapers as well as radio stations providing scant local news coverage.

Schultz reports there’s been pushback, but much seems to be coming from existing newspapers and organizations like the California News Publishers Association. Perhaps they’re feeling the heat by the possibility that small town newspapers could receive much-needed funding.

As Glazer points out, his bill mirrors the same model where PBS, NPR, and public radio and TV stations receive dollars from CPB. I read an abstract of the billl, SB 911, and it’s not clear (to me) precisely which media outlets would be eligible for funding.

But his effort begs a larger question: How are radio stations being funded, commercial or public? Is there a better way? And if there is, why hasn’t someone come up with it by now?

Take commercial music radio, for example. Is the standard funding model the only way to financially power these stations? Could various pages be taken (OK, stolen) from the public radio playbook to create better solutions for a Classic Rock, Hip-Hop, AC or Country station? And via sponsorships and other revenue-generation models, are there other roads to profitability for commercial radio music stations – other than playing 10 (or more) commercials in a row, twice an hour?

And let’s not let public radio stations off the hook when it comes to unimaginative funding models. Putting CPB, foundations, and grants aside, why can’t public radio come up with an alternative to their toxic, shopworn pledge drives?

And let’s not let public radio stations off the hook when it comes to unimaginative funding models. Putting CPB, foundations, and grants aside, why can’t public radio come up with an alternative to their toxic, shopworn pledge drives?

For a medium noted for its innovativeness, these “beg-athhons” ran out of gas decades ago. Even core public radio fans readily admit they go on listening hiatus during “pledge.” And while public radio operators have experimented with more pleasant variations on the traditional pledge drive, shortening them or offering “pledge-free streams” have not successfully moved the needle. The fact is, several times a year – typically in the heart of the spring and fall rating books – public radio stations are at their worst content-wise.

So we’re looking at two major enterprises – commercial music radio stations and the entire public radio system – have fundamental business model problems. The core of their respective funding rubs even their biggest fans the wrong way.

Back in the 20th century, it may not have mattered because there was simply nowhere else to go.

Today, we can’t list them all.

Far be it from me to suggest there are easy fixes close at hand. Because there aren’t.

But neither is especially hot or bothered about finding a solution. Instead outrageous commercial loads compressed into two stopsets an hour and pledge drives are accepted as givens – the price of doing businenss.

Innovation rarely happens by accident. Creative solutions to gargantuan problems never just present themselves. Organizations have to commit to finding big fixes, often spearheaded by their best people.

And just addressing these now-historic messes isn’t going to instantly right the ship. Many of broadcast radio’s issues are existential in nature. New habits have been forming, in some cases, for a generation – or two.

But they might be a starting point.

We have looked at Netflix’s ad-supported model. And while it may not be “the answer,” it could be a starting point to stopping their bleeding. Yes, it’s bold, and runs counter to their original subscription scheme. But it could become the genesis of a solution. Or not.

Earlier this week, Spotify mercifully pulled the plug on “Car Thing,” its gadget designed to gain more presence in connected cars. After just FIVE MONTHS.

It’s OK to “fail fast.” Especially in a fast-moving media environment.

When it comes to facing up to its own major challenges, the broadcast radio machine isn’t even in the race.

It’s at “Full Stop.”

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Call it old-fashioned, but we still put a limit on our spot loads each hour. I won’t say what it is, except that our breaks are half the length of our closest competitor. I know listeners count spots, not the time, but perception wise, it’s still shorter to our audience. Perhaps more frequent, but shorter spot sets are the way?

As far as public funding for privately owned media, I’m very skeptical. I’ve had situations where advertisers would try to push bad programming ideas while hold their accounts over our heads. The government, which holds a lot more power, could not resist doing the same thing.

I’m with you on this, Don. My Eighties Channel clock has a total of three stopsets per hour (the old :20/:35/:50 configuration) with a maximum of four commercial UNITS (and a suggested maximum of three minutes) per stop.

This goes along with my long-held belief in what Bill Drake did some 65+ years ago at RKO: He similarly imposed stopset maximums and when KHJ quickly got to a “sold out” status the sales execs pressured him to loosen his restrictions and allow more commercial time per stop. His response was to increase the rates, and if existing advertisers didn’t want to pay more at renewal, then the units used by them would become new inventory to sell to new ones.

Where we went astray (corporate greed?) was in allowing the “no commercial load” philosophy Fred referenced to take hold. It may not have been obvious when spread throughout the hour pre-PPM, but now the audience notices … all too easily.

If we’d just been like Phil Yarborough all along …

As long as PPM is the “currency,” it could be a long time before many station take the leap back to 3 stopsets an hour. And I didn’t even mention the propensity for most of the stations in metered markets to program their stopsets in the bowtie format, thus infuriating listeners even more. Thanks, Don.

You’re right to shine the spotlight on this perennial problem, Fred. I just wish I could suggest a realistic solution (the conditional-access boat having sailed). I enjoy commercial radio, but I’m primarily a public radio guy and, as much as I loath pledge drives that interrupt important programs, I’ll sheepishly admit to having been one of the voices pleading for pledges when necessary back at my former NPR member station. Oh, the indignity.

For listeners at home or office, subscription-model pledge-free streams could fly, maybe even in the car for listeners who don’t mind burning up cellular data allowances. But it’s already possible to find pledge-free streams if you’re willing to “tune” to an NPR station in another region or state that isn’t currently pleading, errr, pledging. My state’s public radio network is doing it next week and for several days I’ll be streaming Morning Edition from one state away. Of course I am a sustaining member of my own state’s network, but the only perk that really matters isn’t on offer–an uninterrupted signal. I’d take that over another tote bag any day.

You are not alone, John. I’d bet there a lot of people who are “streaming Morning Edition from one state away” every time their favorite public radio station is in pledge. If there’s an audience that understands what it takes for these stations to stay in the black, it’s public radio listeners. And even many of them sit out pledge until their station returns to its normal programming. All the more reason why the best & the brightest need to figure this thing out. Appreciate the comment, John.

The challenge with the “pledge free stream” is that the station essentially has to staff and produce two stations for those time periods. Most small stations don’t have the peoplepower, let alone the budget to do that. It get’s pretty clunky. KQED did it years ago, and I believe they moved away from it. That said, the member drive is the best way to bring in new donors. The sustainers and other regular givers kinda put up with them. And you’re correct about stations shortening up drives. The evidence suggests that station no longer need the week and a half drive. The “Drive” is like a gigantic days long “stop set”. Ha. And stations are figuring out that shorter drives work, and listeners/member will accept even a couple more drives! E.g, Tiny Marfa Public Radio’s “Love Drive” that invites listeners to donate in honor of their sweetie or loved one, and hear their dedication on the air on Valentines day. It’s fun, cute, and about the audience. It’s an exciting time to consider your reminders, Fred, for both commercial and non-commercial business models.

Tim, as you point out, the “Pledge Free Stream” is an idea that’s fine on paper, but is lacking in actuality. And it only is accessible after someone becomes a member. For the vast majority of listeners, the main station in still in pledge. Shorter is better, but as you point out, more creative, personalized ways of giving should be considered. Thanks for checking in.

Well the pledge drives, mostly successful are what drives your local PBS/NPR/public station in many cases. It goes without saying that much of the programming on those stations is valuable to the listener (supporter). I’m a proud part of four PBS stations (Radio and TV) and the pledge programming is very important. Understood that the listener isn’t crazy about it -and we try to make those pledge drives as entertaining as we can -even when when “Morning Edition” or “All Things Considered” get interrupted. We’ve tried some different things in 2022 including shorter (but more frequent) pledge drives. Would this work for “commercial” radio? I’m sure it’s been tried.

But one of the the real villains here is irrelevant content on many commercial stations – in the middle of those horrendously long stopsets. Why is it a station will spend thousands on “music research” and then go muck it up with 11 units in one break? Yeah, sales wants to SELL. Turning down a client creates anxiety in sales managers everywhere. But it should be noted that a cohesive plan for presenting commercials that mirrors the lifestyle and intent of the station’s overall programming can actually increase the PPM (and diary) results -and make the product more desirable to the listener and the client.

Another villain? The PPM methodology that suggests that a station stopping more (even for shorter breaks) gets penalized. Nielsen is supposed to be supportive of broadcasters and their ability to sell airtime-but they’re also acting like judge and jury in the way the “game” works. We could go into sample size later.

Your local PBS/NPR/Public radio station (in many markets) gets great ratings from CONTENT, and you can bet that those stations do research that lets them know what shows work-and what shows don’t.

Again, we come back to the ever present need to feed the bottom line in commercial radio.

Radio has been bleeeding longer than Netflix has but no one at the top seems to recognize that. Radio has competition and the very intelligent people gathering here daily to commiserate as to our fate KNOW the answers. Now, let’s win the Mega Millions and buy that broadcasting company and fix it.

Great comments, as always, Dave. And you are correct that if we’re comparing programming that doesn’t serve the audience, commercial radio “wins” every day. Literally. Pledge drives are a handful of times a year. Incessantly long commercials breaks are every 20 minutes on most music stations on the commercial side. And it never escapes me that Net Promoter Scores in public radio are always 15 more more point higher than for commercial radio – another way the audience is voting. Thanks for the thoughtful perspective.

My little corner of California gets no real NPR signals due to mountains. We put an LPFM on the air here seven years ago to bring NPR-level programming on a hyper-local basis to a city that used to have two weeklies covering the overlaying city, coastal, regional and school government agencies affecting us. Without one penny of government funding, we are doing that. But we are very rare.

My wife and I produce a morning drive all-news block that is 50 percent local content. We carry “The California Report” from KQED, local news from KCRW in LA, and hourly world newscasts from FSN. We carry “The World” from PRX in afternoon drive. During a 2018 fire, KBUU gave continuous evacuation directions all night, until the tower power supply burned down and the studio got singed by flames. Two people do that, at no cost, as well as running all station music, engineering and fundraising operations.

Keeping three HD channels and the main analog going is a major time and effort sink, and this cannot continue forever. KBUU is too small to qualify for CPB grants: they require a minimum operating budget of $100,000, two full time employees and an ERP of 100 watts. Our budget is $8,000, we have zero employees, our ERP is 71 watts. NPR requires five full time employees for membership, but would license us All Things Considered and Morning Edition for $62,000 per year, last time we checked. They need us far more than we need them.

Our community is Malibu. When we needed to buy HD transmitters to provide synchronized analog service via boosters, wealthy donors stepped right up. When we needed to buy gasoline for four generators after the fire, Malibu stepped up – heck, we got “fill the gas can today” donations from people in Ohio, in England. and when we needed solar panels, a local rock star stepped up.

Not every small town in California has that kind of resource. California can afford to invest in local news coverage via nonprofit radio. At KBUU, we look forward to hiring some help and growing the station, maybe with a modest amount of support from Sacramento, awarded on need and merit.

Hans Laetz

GM, engineer, operations manager, underwriting coordinator, news anchor, weed chopper,

KBUU-LP FM HD1, 2 and 3, Malibu

Hans, great story & thanks for sharing it. Hopefully, you and your wife will get a little relief from your government representatives. Sounds like KBUU is a labor of radio love. Make mine a men’s large. And if you’d like to donate to KBUU, visit their website. http://www.radiomalibu.net/

May I chime in here? I’ve known Hans for a few decades now and KBUU is a shining example of what LPFM was designed to accomplish for local communities.

Absolutely! What a great story! What would radio look like today with more Hans’ steering these ships!

PS t-shirts available – $50 donation – see web site.