Maybe you saw that amazing story in The New York Times Magazine last month. “The Day the Music Burned” by Jody Rosen is an amazingly detailed analysis of a music story most of us knew little to nothing about. Seth covered it in his “Connecting the Dots” blog – and its relevance to radio struck me, especially with last week’s headline about Taylor Swift’s first five albums.

So, here’s the story. In 2008, a fire blew through a Universal Studios Hollywood lot, including several familiar movie sets, as well as a back warehouse. It turns out that building contained a treasure trove of classic Universal Music Group recordings – the original raw masters of individual studio tracks by hundreds of musicians.

The fire was downplayed at the time, but it turns out irreplaceable archive material – and a ton of it – was destroyed in that fire.

Rosen sums it up this way:

“It was the biggest disaster in the history of the music business.”

From the old days, we’re talking about recordings from Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Judy Garland.

Then there was the blues – Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Etta James and many more – recordings that were lost forever.

Rosen tells us almost all of Buddy Holley’s masters went up in flames, along with a list of other iconic artists that is mind-boggling:

Sammy Davis, Jr, Neil Diamond, B.B. King, Eric Clapton, the Four tops, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, Guns N’ Roses, Beck, Steely Dan, Aerosmith – and hundreds more. And those are just some of the ones they know about. Think about all the obscure artists whose recordings literally went up in flames that June day, never to be heard again.

In his story, Rosen lovingly describes what it means to have lost these treasures in the Universal fire. I’ll leave the task of reading his amazing chronicle of this disaster to you, rather than try to paraphrase his brilliant writing. It speaks for itself.

But suffice it to say, I read Rosen’s potent essay and began to think about just how many radio station archives are treated as cavalierly as this stash of priceless recordings. There was no fireproof vault or even great care taken to protect these gems, unlike the ways in which galleries protect paintings.

Why was the Universal fire hushed up at the time? Rosen suggests it was about how the artists themselves might have reacted had they known the full extent of the blaze. These masters are precious to musicians.

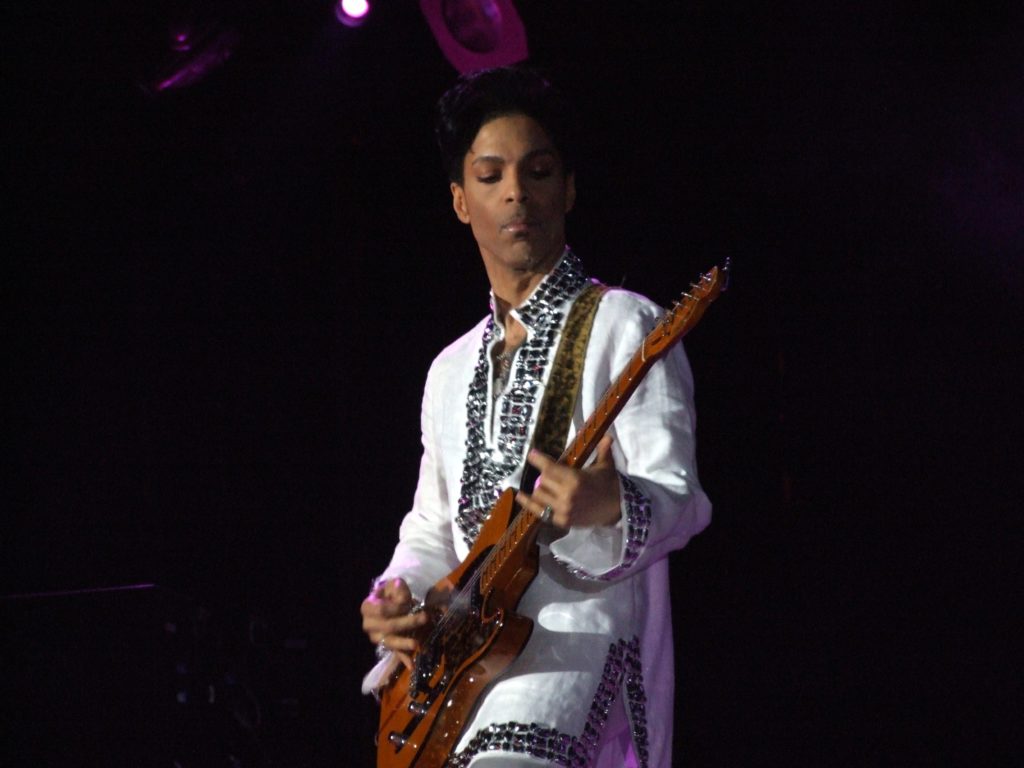

And Rosen quotes Prince who once noted while involved in a dispute with Warner Brothers, “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.”

And Rosen quotes Prince who once noted while involved in a dispute with Warner Brothers, “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.”

The Universal blaze may, in fact, be the worst disaster of its kind. But Rosen chronicles other debacles that ended up destroying all sorts of recordings. A lot of these have been due to what he calls “shoddy storage practices,” along with mislabeling, misfiling, and other screw-ups.

Rosen points the finger at how the structure of the music business has changed over the years, as smaller companies have consolidated into a handful of big ones. He points out that in the heat of sales, IPOs, and calculating EBITDA, no one may be thinking a whole lots about the archives.

Rosen also notes that proper storage and protection of recordings is far from cheap. And as we know from radio experience, the first thing that happens in a merger, buyout, or takeover is cost-cutting and economies of scale.

And that’s what Taylor Swift is experiencing right now, as a result of the sale of her former label, Big Machine, to manager Scooter Braun.

That rekindled a Swift/Braun feud that dates back to that uncomfortable interlude with Kanye West. Braun now owns the master recordings to Swift’s first six albums. As The New York Times remind us, that means controlling the rights to song licensing for movies, TV, and video games, in addition to how and where her tunes appear.

In this case, Swift lost her archives to a questionable business deal. But that doesn’t change the importance of these irreplaceable assets.

So, what does this have to do with radio, aside from the obvious music connection?

When I read “The Day the Music Burned,” it was around the time that WPLJ was in its final throes, waiting to be extinguished by a new owner and a completely different format.

Yes, the call letters were going away, the format was over, and management was left to selling commemorative T-shirts.

But what of the WPLJ archives? Who ended up with them? And have they even existed all these years, as the station was sold from ABC to Cap Cities to Citadel to Cumulus?

But what of the WPLJ archives? Who ended up with them? And have they even existed all these years, as the station was sold from ABC to Cap Cities to Citadel to Cumulus?

Like the majority of radio stations in America, WPLJ changed hands, not once, not twice, but several times. That describes some of the biggest and best call letters in the U.S.

And here’s an example that occurred to me during the “celebration” of PLJ a few weeks back: Elton John famously recorded a live album that was broadcast on PLJ (then WABC-FM) in front of a small audience. Called 11-17-70, it is an amazing performance by an artist who was just emerging at the moment in time. The pictures, the interviews, the songs that never made the album?

I was thinking of that amazing moment – capturing an emerging superstar on the radio – while watching Rocket Man a few weeks ago. No, that moment wasn’t covered in the film, but New York radio fans of a certain age probably recall it well.

So what of PLJ’s archives, its rich history, the photos, the interviews, the TV spots, the merch, the recordings?

For every station like KSHE where so much of their material was lovingly saved, protected, and ultimately put on display in their online “Real Rock  Museum,” there have to be scores of stations where the archives have been lost, disappeared, or pillaged by staffers during moves and sales.

Museum,” there have to be scores of stations where the archives have been lost, disappeared, or pillaged by staffers during moves and sales.

Think about stations like WBCN, KMET, the Loop, and so many others. What happened to their histories, their pasts? How will we remember them even a decade or two from now if these artifacts from their past no longer exist?

It makes you wonder if the radio industry – and certainly the bigger companies – could derive value out of archivists – record-keepers, protectors of radio’s past.

But that would cost money – perhaps plenty of it – to save, salvage, preserve, and protect these materials.

Come to think of it, the only consistent “archiving” the radio industry has been engaged has been done voluntarily by an aging videographer here in Michigan – Art Vuolo.

Everyone knows Art – if you go to virtually any radio conference, from Don Anthony’s Boot Camps to Conclave to the Worldwide Radio Summit, there’s Art, recording the event on video so that future generations might understand just what the business was all about last year, last decade, or during a time when you weren’t even born.

Watching Art’s Archives from the early days of radio is a reminder of how the business has changed – and how it hasn’t.

Over the years, Art Vuolo has become known as “Radio’s Best Friend.” That’s because he has selflessly took it upon himself to get his beloved industry down on video so we – and our kids and grandkids – can enjoy it. If you’ve had a chance to talk to the man behind the camera over the years, you know he loves radio more than many people who have earned riches and fame from being behind the mic or sitting in the corner office.

Over the years, Art Vuolo has become known as “Radio’s Best Friend.” That’s because he has selflessly took it upon himself to get his beloved industry down on video so we – and our kids and grandkids – can enjoy it. If you’ve had a chance to talk to the man behind the camera over the years, you know he loves radio more than many people who have earned riches and fame from being behind the mic or sitting in the corner office.

But if you’ve also noticed the past few years, Art is no longer that bouncy thirtysomething guy wearing his prized WLS sweater, running around hotel ballrooms with a camera on his shoulder. Travel has become more difficult, and you can look in Art’s eyes and know the day will come when he will put that lens cap on his video camera for the last time and call it a career.

He’s “Radio Best Friend” alright, but he’s also “Radio’s Only Archivist.”

There’s a handful of others – “Radio Rewinder” (@radiorewinder) publishes old playlists, photos, and stories from long-gone publications like Radio & Records. My old MSU radio buddy, Scott Westerman, has done an amazing job archiving Keener 13 – the legendary Top 40 station here in Detroit that so many Baby Boomers grew up with in the ’60s.

& Records. My old MSU radio buddy, Scott Westerman, has done an amazing job archiving Keener 13 – the legendary Top 40 station here in Detroit that so many Baby Boomers grew up with in the ’60s.

But these efforts are few and far between. Oddly enough, the phrase “keepers of the flame” came to mind when I started thinking about the Universal fire, and the neglect that has surely happened throughout the radio industry and its history these past several decades.

The past is the past.

But not to be able to remember it, celebrate it, and share it with future generations is just sad.

You can read Jody Rosen’s story here.

Thanks to Randy Kabrich who was the first to send it to me.

- Can Radio Afford To Miss The Short Videos Boat? - April 22, 2025

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

http://www.americanradiohistory.com is another great resource for old radio related publications.

Glad you mentioned that, Kurt. David Gleason (ex-Univision) has made it practically a holy quest to find and digitize every issue of every defunct industry publication.

Would you believe that every single issue of Broadcasting is there? And a good chunk of Radio & Records?

He even has a complete set of the old Broadcast Programming & Production (about half of which came from my copies, loaned for scanning) and the ill-fated Panorama, published by TV Guide in the early years of satellite networks on cable (all of those came from me).

And I would be remiss if I did not mention that even though its founder, Richard Irwin, passed away last year, the top-40 aircheck archive ReelRadio (https://www.reelradio.com) is still online, thanks to it being “owned” by a non-profit 501(c)(3) entity. It even has the infamous WPLK pirate aircheck!

KM, thanks for filling in some of those blanks. I have heard from a variety of hobbyists and others who have taken it upon themselves to build and maintain collections. Appreciate it.

Appreciate that, Kurt. Thanks for letting us know.

The Missouri Broadcasters Association is collecting radio recordings that are housed at the Missouri State Historical Society.

Good to hear, Terry. Thanks for the heads up.

My first reaction was “archives? What archives? Very few stations kept any copies of on-air aircheck material, so it seems. Stations ran slow-speed logger tapes for legal compliance purposes, but very few were ever rescued from the trashbin, let alone be restored and made available online. Among those that were, a handful of full broadcast days of The Big 8, CKLW, including New Year’s Ever, 1973 into 1974, some of WOWO in Fort Wayne including The Little Red Barn–you’ll find them on historyofwowo.com—and several stations, including WBAP, KLIF, and WLW on the day of the JFK assassination. WLW’s full broadcast day leading up to assassination coverage was uploaded to YouTube as well, providing a rare glimpse of early 60s full-service programming. (You’ll also find the only full-length episode of Ruth Lyons’ 50-50 Club known to exist. The long-running show was simulcast on WLW radio and the WLW Television stations from the 50s throgh the 80s and was hosted by Bob Braun after 1967). Still, if it wasn’t for kids trying to record their favorite songs, and DJs who held onto airchecks, we wouldn’t even have remnants of KHJ, KFRC, CKLW, WLW, WABC, etc that we have on reelradio.com, rockradioscrapbook.ca, Airchexx.com and others. It’s too bad other formats weren’t preserved as well as Top 40.

Based on the number of conversations I’ve had with friends in radio who are collectors, I think you’re exactly right, Brad. Top 40’s jingles, jocks, and fun were all part of so many kids’ lives growing up. Fortunately, a few of those “kids” starting archiving audio and other artifacts as you point out. Thanks for the comment.

I’m very proud to be associated with a couple of Minnesota-based websites that (in my opinion) have made the Minneapolis/St. Paul radio market one of the most archived markets in the country. Between Tom Gavaras’ radiotapes.com and Rick Burnett’s twincitiesradioairchecks.com, there is aircheck material from every signal in this region and audio going back to the 1920’s.

There are dozens of aircheck sites around the country that specialize in their own areas, and it’s time we unite them all to a common purpose in saving the evidence of what so many of us have worked decades to create.

Airchecks are not just a radio nerd hobby – they are essential preservations of our culture over the last 100 years!

Jay, couldn’t agree more. I’ve learned a lot since writing this post. There’s more being done than I thought – but not by the radio industry, but instead by enthusiasts, collectors, and in your words, nerds. Thank goodness for them all. Some have a better sense of the meaningfulness of radio than those of us who have worked in the business for decades. Pulling all this together might be a Herculean task, but really good for the industry. Appreciate the comment.

After collecting over 500 local airchecks for the St. Louis Media History Foundation’s archive, I’m now proud to be associated with the Radio Preservation Task Force, an effort with the Library of Congress. Our group is assembling a database of all aircheck collections so researchers and other interested parties can find station-or-personality-specific airchecks. More info is available from [email protected]

So happy to hear from another local archivist, Frank. I’m not surprised this is happening in St. Louis, long a proud & great radio market. Appreciate the heads up.

The Library of Congress has convened a project to support radio preservation. I am happy to answer any questions about the project.

https://www.loc.gov/programs/national-recording-preservation-plan/about-this-program/radio-preservation-task-force/

Best Regards,

Josh Shepperd