Yesterday’s post about radio’s successful reinvention when millions of TV sets appeared in American rec rooms and dens in the 1950s is a stimulating and hopeful story about the medium’s resilience. Radio benefitted from smart, savvy thinking from programming icons like Bill Drake, Todd Storz, and Gordon McLendon, coupled with fortuitous tech inventions like the transistor and FM radio. The confluence of those pieces allowed radio broadcasters to create a different relationship with a mass audience built around music, personality, and a connection to local communities.

Many have suggested that because of radio’s success seven or so decades ago, the possibilities for it to happen again are excellent. This appears to be supported by the fact that while other traditional media such as newspapers and local television have shed audience, radio’s reach has held up remarkably well, in spite of novel Internet content and gadgetry. The oft-stated “radio’s not going anywhere anytime soon” – or words to that effect – have been regularly heard from industry leaders while defending the medium’s continued efficacy. While radio has struggled to attract young consumers and to create viable digital content verticals, many broadcasters continue to express optimism a renaissance is possible.

We heard a lot of chatter along these lines during the podcast resurgence following the impact of “Serial,” now a decade ago. Many broadcasters attended industry events such as Podcast Movement, eager to be players in this new era of audio consumption. The thinking was that the same skills required to produce successful podcasts exist among many radio broadcasting hosts and production directors.

But the facts suggest that for radio, this was a false positive. Few memorable podcasts have been produced by radio broadcasters, relatively speaking. Most of the radio companies participating in the podcast arena have bought their way in, rather than created successful shows from the ground up. And even in cases where quality podcasts were produced at the station level, sales departments have had little success in consistently monetizing them.

But the facts suggest that for radio, this was a false positive. Few memorable podcasts have been produced by radio broadcasters, relatively speaking. Most of the radio companies participating in the podcast arena have bought their way in, rather than created successful shows from the ground up. And even in cases where quality podcasts were produced at the station level, sales departments have had little success in consistently monetizing them.

Over the last decade, most of the “successful” podcasts created by radio broadcasters are simply repurposed morning shows or the on-demand version of over the air programs.

And that brings us to an inflection point in this 30-year period since the Internet became embedded into our society, our culture, and our entertainment/information model. During this time, there’s been no shortage of attempts by radio stations and companies to create marketable digital content. But how much of it actually stands out as an exemplar of radio’s best new media efforts? In fact, it is not difficult to think of many great radio stations created in the second half of the 20th century. It is far more difficult to think of stellar digital content over these past three decades.

Let’s take a look at websites, for example. Almost as a rule, radio station websites are generally poor examples of aesthetically pleasing, novel websites. In fact, most resemble the outfield wall of minor league baseball parks, riddle with a crosshatch of ads and promotions. Like podcasts, few stand out as successful examples created by radio.

Radio – a medium that once aspired to excellence in making great stations, shows, personalities, and even commercials has settled for whatever passes as mediocre in a marketplace where great content is no longer scarce – it is everywhere.

The last several years, especially since the pandemic, have been rugged for the radio broadcasting industry here in the States. On the commercial side, RIFs have become so common we no longer express shock or surprise when they happen. While they have obviously shaved expenses in order to plump up the bottom line, more and more stations and clusters have been depleted and often gutted in order to reduce head counts and expenditures. But have they streamlined or improved operations? Or are the remaining few simply tasked with wearing more hats?

surprise when they happen. While they have obviously shaved expenses in order to plump up the bottom line, more and more stations and clusters have been depleted and often gutted in order to reduce head counts and expenditures. But have they streamlined or improved operations? Or are the remaining few simply tasked with wearing more hats?

2024 has been an especially painful year for public radio as we learn how more and more stations are miles away from break-even, often running up seven figure deficits. The “answer,” in most cases, has been to shutter content centers – often podcasting units – while offering buyouts to existing staffers. And if that doesn’t work, layoffs. But is the net result a positive for public radio? Are we seeing stations making smart content decisions in the wake of all the red ink? Or are managers continuing to intuit their way out of the financial abyss?

Back in the good old radio days of yore, strategic content choices weren’t all that hard to make. True, great talent in the early stages always involves guesswork and gut. Same with the calculus of whether a show or a format might actually find a sustainable and substantial audience. But over the years, most broadcasters adhered to a design and execution protocol, based largely on audience research on other linear diagnostic tools.

Plus, we had the ratings. And before you fall on the floor laughing in tears, remember that early indicators from Arbitron were generally a reasonably good barometer of success. Sure, it always helped to supplement “the book” with perceptual research to gain extra insights about the projected fortunes of your creation. But you didn’t need a dashboard or a data scientist to know whether you had a hit on your hand. And there was essentially that single source of numbers that defined success, failure, or perhaps “giving it another book.”

Plus, we had the ratings. And before you fall on the floor laughing in tears, remember that early indicators from Arbitron were generally a reasonably good barometer of success. Sure, it always helped to supplement “the book” with perceptual research to gain extra insights about the projected fortunes of your creation. But you didn’t need a dashboard or a data scientist to know whether you had a hit on your hand. And there was essentially that single source of numbers that defined success, failure, or perhaps “giving it another book.”

In the digital morass, the going’s been tougher. Obviously, there’s a lot more content coming from myriad sources – known entities as well as amateurs in their garages or spare bedrooms. An “influencer” can materialize out of nowhere, attracting eyeballs and dollars without the need for costly towers, transmitters, and other equipment that presented barriers to so many content creators. Today, anybody with a couple hundred bucks and a concept can create a podcast that is successful on one metric or another without a license or a special pass.

And it doesn’t stop there. Ordinary citizens can launch games, social media franchises, record labels, video channels, even blogs. 🙂

So in this highly-charged era of the creative economy, radio organizations (that’s what they still are) need to significantly improve their success ratios, their batting averages, if you’ll excuse the lazy sports analogy. To that end, Willie Mays’ passing last week was a reminder to all of us who aspire to be professionals in our chosen fields how hard that truly is to accomplish. Excellence is fleeting and it rarely happens by accident. Few are so gifted they can simply roll out of bed and create digital content that will capture an audience and make money. If it were that easy, everyone would do it.

To that end, Willie Mays’ passing last week was a reminder to all of us who aspire to be professionals in our chosen fields how hard that truly is to accomplish. Excellence is fleeting and it rarely happens by accident. Few are so gifted they can simply roll out of bed and create digital content that will capture an audience and make money. If it were that easy, everyone would do it.

That’s why I refer to much of the gyrations radio has gone through these past 30 years as mostly “random acts of digital.” Someone walks into someone’s office, declares she’s got a great idea for a podcast, and it just may see the light of day. It doesn’t stop there. How many drawing board ideas somehow got green-lighted despite an obvious lack of due diligence – asking the right questions and demanding rational, sensible answers?

So that’s what I tried to put together in the paragraphs that follow below – the questions that need to be asked before something gets produced, coded, taped, edited, published, dropped, or broadcast. My laundry list of key questions to isn’t all-inclusive, but it’s a good start. And at the end of the list, I’ll offer suggestions about how to use it in the hope the organizations in our space improve their batting averages.

Here goes:

1. Is there a need for it in your market or space? Fundamental, but how many ideas that somehow rise to the top aren’t original, and there isn’t a crying need for another one. Do your homework. If you’ve got a great idea for a new mobile app, do those searches in the big app stores to see if someone has already done it. None of this suggests you can’t do it better. But it is sure helpful to know on the front end what you’re up against.![]()

2. Is it “evergreen?” That is, will it last – like interviews with famous people – or is it a one-and-done? Again, there’s room for everything in the world of content creation, but planning and budgeting will be much smoother when you account for having archival material that can be repurposed and/or monetized.

3. Is it sustainable? It’s never easy to create a piece of content that can last a number of seasons – or years. But there are many that are designed to spawn other versions, like prequels and sequels, versus those that are fated to likely be one-offs.

4. Is there a CGC component? Consumer generated content, of course. When your audience, following, or community can add to the episodes, versions, or chapters, you’ve got a product that can have a nice long life – a good thing.

5. Is it habit-forming? We know what this looks like in radio – benchmark bits that fans keep coming back to day after day. When you create something audiences want to make a part of their routines, you’ve![]() created regularity, a wonderful quality for a brand to have.

created regularity, a wonderful quality for a brand to have.

6. Is it doable? Maybe this one should be moved up to the first position because so often, teams take on projects that simply cannot be done with existing resources – financial, human, or both. Oh yeah, and time.

7. Who is it designed for? Who is the target market for this creative content, and can that be expanded over time? Many ideas, of course, start young and then work their way through older generations of consumers. What’s the demographic trajectory of this concept?

8. Can you monetize it? Let’s move this one up, too. How many seemingly strong projects have died on the vine because there was ultimately no market for it OR the salespeople couldn’t (wouldn’t?) sell it? For a brand new project, of course, there are no guarantees. But finding a sales rep (or two) who are truly enthusiastic about the concept can often solve myriad problems in the early stages. This is the Achilles heel of so many organizations. Solve it and you’re halfway home.

9. Do you own it or rent it? Content creators often neglect to consider whether the material is theirs – or actually belongs to Mark Zuckerberg, Tim Cook, Elon Musk, or some other tech titan. You own your database, your newsletter, your podcast, or a game you created. You don’t own your YouTube or Twitch channel, or your Facebook page. When the “landlord” can change the rules at any point in time or end your franchise altogether, that’s a real bad day.

database, your newsletter, your podcast, or a game you created. You don’t own your YouTube or Twitch channel, or your Facebook page. When the “landlord” can change the rules at any point in time or end your franchise altogether, that’s a real bad day.

10. Can it be brand-extended? That is, could your creative content become an event, move over to other media like a newsletter, move into video, or have a merch component? Content brands that have expansion capabilities can have sustainable success.

11. Is it personality-dependent? And/or can the addition of a face or name make it bigger/better? If there is a personality involved, does the concept become vulnerable if that person exits, for whatever the reasons?

12. Does it have an existing track record? Has someone else done this – or something like it – and what can you learn from their effort. Back in the old days of radio, you had to fly somewhere and sit in a Holiday Inn for a couple days to hear how that new station sounded and its architecture. It’s a lot easier today to learn from those who have tried it, succeeded, or failed.

13. Where’s the fan base? Is this creative piece going to target your P1s or a secondary/tertiary audience? Figuring out (in advance) how hard you’re going to have to work to expose it and market it is key to getting the word out quickly. How many good ideas have failed because of the difficulty and expense to promote them?

getting the word out quickly. How many good ideas have failed because of the difficulty and expense to promote them?

14. Can the audience be digitized? Can we easily obtain key information from the folks who consume this content? Unlike the over the air radio product where we have no idea who listeners are, content like newsletters lend themselves to capturing email addresses and other data. Sadly, podcasts, websites, and so many other examples of new media content make it it difficult if not impossible to save the digital fingerprints of audiences.

15. Is it easily shareable? Unlike terrestrial radio stations, many examples of digital content – newsletters, videos, social media posts – can easily be shared, distributed, and passed along. If it’s good, is it in a format where the audience can do the heavy lifting?

16. Is it a logical extension of the parent brand? That is, does it make sense you’re doing it? Does it enhance your brand or is it incongruous?

17. Is there existing research that would help inform the content? It could be research your organization has done or data from existing studies like Infinite Dial, Techsurvey, or the many online resources on the Internet that can be helpful in providing insights on your digital concept.

resources on the Internet that can be helpful in providing insights on your digital concept.

18. Do you have expertise? If your content is going to focus on an area where you have some knowledge, but aren’t an “expert,” consider finding a partner who does. If you are going to focus on food, partner with a local celebrity chef or a gourmet grocery store, for example. If not, fans will see right through you.

That’s my starter list. Putting your proposed digital content through these paces would be a more extensive exercise than many organizations do. In fact, you might even want to weight some of them (like “monetization,” for example) if you feel its considerably more important than others (like “shareability”).

Not every idea is going to bat 1.000. In fact, an average of .500 might be good – where you can check off half of these (or more). Less than half might mean the proposed digital content has promise, but needs work. And if the concept only hits just a few of these pre-reqs, maybe you’ve got to ask, “What were we THINKING?”

And for encouragement, think about the one media operation that is achieving greater success in the digital content arena than any other media brand – the New York Times.

Now some of you reading this may simply write off this example because of the brand’s size, historic success, deep pockets and huge staff. But keep in mind, they’re a newspaper (or at least they were), stuck with falling circulation and all the other baggage that comes along with print media.

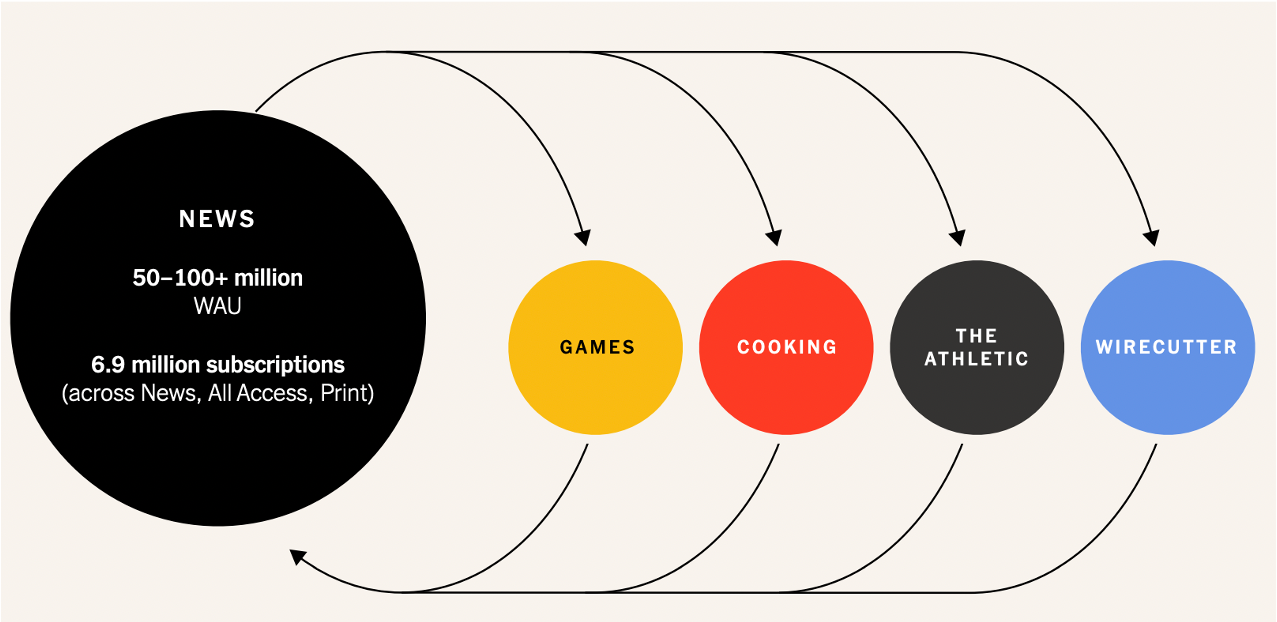

Their creation of digital verticals like “Games” and “Food” isn’t just brilliant, these concepts expertly answer many of the questions posed above. The Times didn’t just fall into these extensions. They are the products of smart, tuned-in strategic planning.

And there’s a symbiotic quality to them all. Not only do they stand on their own, but they each feed audience – and subscription revenue – into the umbrella New York Times brand. You don’t have to read the newspaper in order to subscribe to “Games,” but one day, perhaps you will. The flow from one digital extension to the next will only grow as the company nurtures and takes care of them.

There’s a lot for radio to learn from this process. The last three decades have been challenging. The last three years have been brutal.

Radio organizations must do better in this challenging arena of digital content creation or the industry will be doomed to repeat its mistakes – or worse.

Asking the right questions on the front end can prevent many of the tears so many are shedding now.

- The New Pope Was Selected Faster Than Most Radio Organizations Hire New CEOs - May 12, 2025

- What If Radio Tried Something Right Out Of Left Field? - May 9, 2025

- Why Radio PDs Are A Lot Like NBA Coaches - May 8, 2025

Three days later, still no comments from the industry? If that’s not an omen, nothing is.