Today’s “Best of JacoBLOG” entry goes back almost one year in time. And it’s a post about a topic that is near and dear to me – and most of you:

MUSIC

Most people working in radio originally walked through one of the many “music doors,” whether it was Country, Rock, Hip-Hop, Top 40, or even narrower passageways like Jazz, Classical, or Triple A.

Like just about everything else in our lives, music has been disrupted by both technology and the times in which we live. The way that music is made, sold, marketed, and exposed has been turned upside-down by social media, digitization, data mining, and other factors most of us could never have imagined a few decades ago.

Back then, it was a world of auditorium tests, callout, and even calling record stores every Monday to get a sense for what was selling. And that “old technology” figures into today’s discussion about new music, old music, what’s working, and why. – FJ

January 28, 2021

How can new music compete against Classic Rock? That is the question, as ironic as it may sound.

Nearly four decades ago when I was trying to just get ambitious broadcasters to take a risk on an all-gold radio format on the FM band, featuring the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, and the Eagles, I never could have dreamed anyone could possibly ask that question.

Back in ’83, the world of radio revolved all around new music. MTV was hot, fresh, in your face, and exciting, while mega-artists like Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Hall & Oates were ripping up the charts. Top 40 radio was experiencing not just a renaissance, but a massive wave of success. Mike Joseph’s “Hot Hits” pop radio format was generating massive ratings – and lots of cash.

Back in ’83, the world of radio revolved all around new music. MTV was hot, fresh, in your face, and exciting, while mega-artists like Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Hall & Oates were ripping up the charts. Top 40 radio was experiencing not just a renaissance, but a massive wave of success. Mike Joseph’s “Hot Hits” pop radio format was generating massive ratings – and lots of cash.

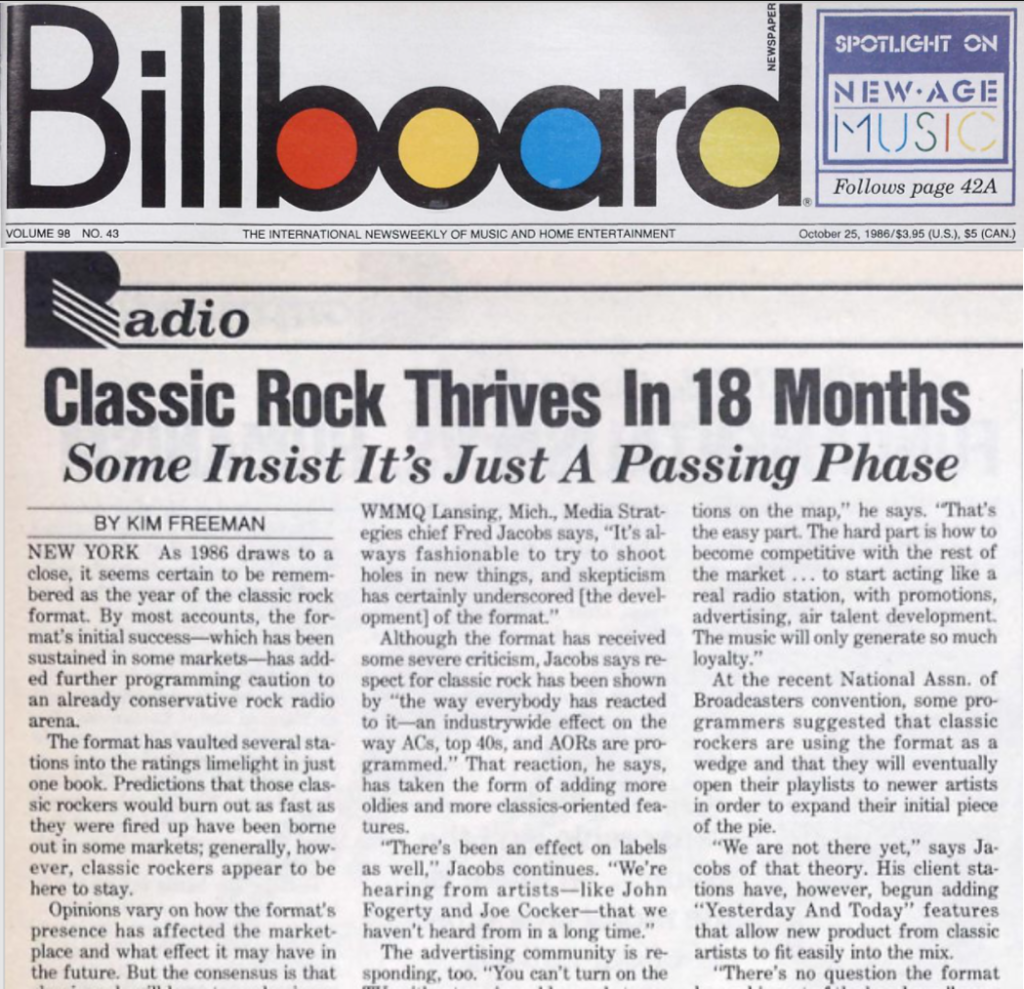

Still, there was much grousing in the rock music community as Classic Rock radio stations began to get traction in Arbitron, often at the expense of the rock stations in town. And it didn’t take long for me and other programmers to feel the heat from the labels. The story you see at the top of today’s post is about 35 years-old.

Billboard reluctantly covered the format’s ascent at the 18-month mark, and its impact on mainstream rock. As writer Kim Freeman concluded, “Classic rock (radio) appears to be here to stay.” As the headline conjectured, “Some say it’s just a passing phase.”

That was then. This is now. And in many ways, very little has changed.

Just last week, a story in BBC News by Mark Savage carried this ominous – but modern – headline:

“Classic bands accused of crowding out new music on streaming services”

As we’re nearing the two-year mark of COVID, more and more bands are feeling the pain of no touring and meager merch sales. And as they’re learning, musicians cannot live by streaming royalties alone.

And they’ve taken their plight to Parliament in an effort to get resolution. Savage tells the story of musician Nadine Shah (pictured) who “has been forced to move back in with her parents” due to insufficient earnings from streaming. (As other Millennials might remind her, join the club.)

It is undeniably difficult for new, emerging artists to break out under the shroud of the pandemic. But some of the proposed remedies that attempt to even out the music streaming playing field coming out of the UK are creative, but patently absurd.

It turns out that in 2019, three of the country’s top 10 best-selling albums were greatest hits compilations by Queen, Elton John, and Fleetwood Mac – artists old enough to be Natalie Shah’s grandparents.

David Joseph, CEO of Universal Music UK, offered up a novel suggestion that would help more obscure artists like Shah: streaming services might institute a user-centric royalty where if you listened to an emerging artist like Shah during any given month, “your entire subscription fee would go directly to her,” rather than to Elton John or Adele.

Something tells me that concept won’t fly.

From the beginning of recorded music history, new artists have had to hack it out against established stars. Clearly, COVID exacerbates this battle, but today’s future hit-makers and emerging artists have always had to compete against behemoths that offer familiar music – and memories – from the past.

The problem during COVID has been exacerbated by so many artists sitting on the sideline, waiting to release their next project until the pandemic dies out. In retrospect, you have to question that logic because being holed up at home is the perfect environment for music discovery and appreciation.

How else would you explain the observations by Julian Chokkattu, a writer for Wired who penned an insightful first-person essay last month about the tactile joys of intentionally listening to an album (both sides), rather than random songs on a Spotify playlist. Consider his quote about the enjoyment of albums played on a turntable:

How else would you explain the observations by Julian Chokkattu, a writer for Wired who penned an insightful first-person essay last month about the tactile joys of intentionally listening to an album (both sides), rather than random songs on a Spotify playlist. Consider his quote about the enjoyment of albums played on a turntable:

“Music quality isn’t why I’ve been so enamored by this new hobby. It’s that physical experience of using a turntable; the sensation of the soft crackle before a track begins; along with finding, curating, and seeing a stack of records grow in my media console that’s made the most dramatic impact.”

It’s not just a handful. At the same time Boharik was enjoying a Ray Charles album, the Consequence of Sound shared Billboard data revealing more 1.8 million albums were sold in the U.S. during the week before Christmas – the all-time record since Nielsen/MRC Data started tracking this stuff. Previous records were set during the prior weeks of December last year.

During that record-setting week, the top-selling vinyl album was Paul McCartney’s new masterwork, III. It sold 32,000 units, making it the biggest selling vinyl record in nearly three decades. Sorry, Nadine.

Radio still plays a starring role in the airplay/sales equation. But discovering great music has been made more complicated by fragmented exposure due in large part of having a multitude of disparate distribution outlets. Even in the ’90s, an artist either had radio play or went home. Today, there are lots of places where new music is being exposed. It’s just become arduous to amass enough critical mass exposure to make a living.

Today, broadcast radio isn’t what it used to be, but still remains essential for success. Airplay from streaming services, YouTube, or satellite radio play a role, as does music featured in movies, TV shows, and in newer sources like TikTok videos. Programmers can learn a great deal about the music and how it is being enjoyed by fans on different platforms.

play a role, as does music featured in movies, TV shows, and in newer sources like TikTok videos. Programmers can learn a great deal about the music and how it is being enjoyed by fans on different platforms.

That’s a far cry from calling record stores every Monday, and conducting crude callout research among small samples of listeners – two of the most popular tools for gauging hits back in the Cro-Magnon era when I last programmed.

Today, the science – and art – of finding hits is a topic of conversation, especially in the age of COVID when new music has wilted. Or has it?

This is a topic that’s been popular the past couple weeks in The Sands Report, the trade publication devoted to Alternative radio. Richard Sands queried a number of luminaries from the programming community, pondering where hits are coming from and how to find them.

This is a topic that’s been popular the past couple weeks in The Sands Report, the trade publication devoted to Alternative radio. Richard Sands queried a number of luminaries from the programming community, pondering where hits are coming from and how to find them.

On the one hand, modern tools like tracking Shazam histories can be telling, but not necessarily indicative of whether an emerging song might actually go on to become a hit. Ultimately, some of Richard’s questions – especially this one – merit conversation:

How Can The Format Do A Better Job Building Artists?

He’s talking ALT, of course. But that’s a big question, because artist centricity is a big reason why music formats have always had legs. The audience (and radio) helps establishes its “Mt. Rushmore Artists.” And radio programmers and music directors respond accordingly when new music is released by a core band or one comes to town to play a concert – or two.

Makes sense, right? Until it doesn’t.

Without albums, it is downright difficult for artists to establish strong, reliable bases of loyalty and scale. We now live in a world of singles, of one- offs, where it becomes daunting for artists to gain any level of long-term fan traction.

offs, where it becomes daunting for artists to gain any level of long-term fan traction.

Back in the ’60s and ’70s when a whole new roster of great artists established their franchises, they had a body of work from which to draw; catalogues of music to be enjoyed by new fans and old stalwarts alike. Album art and liner notes illuminated the bond, creating deep connections between artists and fans.

You got “into” a band. You talked up an album. Consumers were promoters – and not because they were paid to “influence” tastes.

Today, there are no albums. And thus, loyalty becomes transient. It is about songs – not artists. And that makes radio programming a much more dangerous profession.

That’s when I started thinking about how streaming and song skipping have changed the way real people enjoy music, and the crying need for radio’s remaining PDs to educate themselves on the myriad ways music is being consumed in this millennium.

And I flashed back to Lee Abrams (pictured left), and his visionary Superstars rock format from the ’70s that changed the sound of radio, as well as shaping music tastes for decades.

And I flashed back to Lee Abrams (pictured left), and his visionary Superstars rock format from the ’70s that changed the sound of radio, as well as shaping music tastes for decades.

One thing that hasn’t changed about the world of labels is that hit singles are chosen based on a variety of factors, some sensible and some irrational.

And aside from that first release, programmers were tasked with finding other great tracks on the same album that might be as good as – if not better than – the single.

Abrams came up with a novel way to figure this out – or at least to derive important clues.

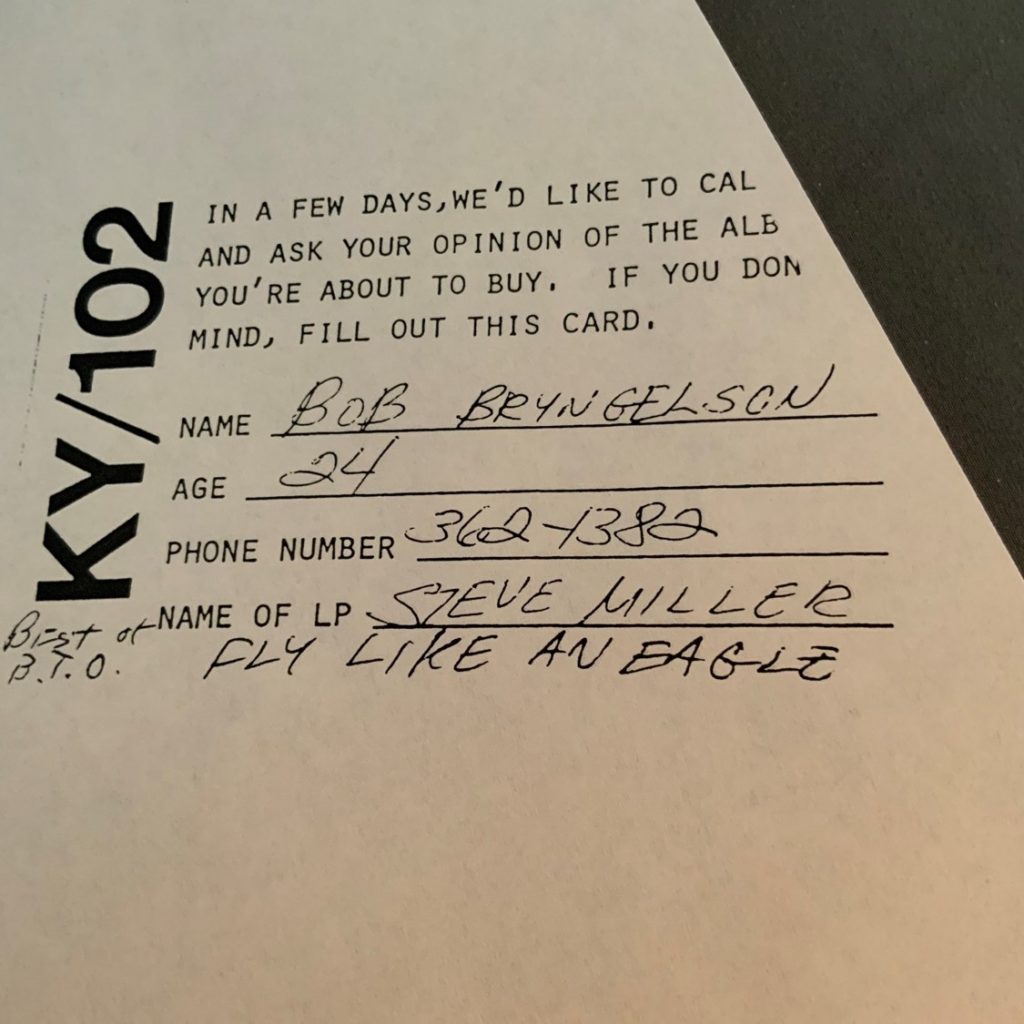

He placed simple cards in record stores in his client markets like the one you see below. Every time someone bought an album, they were asked to fill one of them out.

A phone call back to these album buyers revealed important patterns in determining secondary and tertiary hits, because back then, most people listened to entire albums – again and again and again. Who better to pinpoint other great songs from these collections than people who invested a few bucks in those albums to begin with? Given the cover-to-cover way in which just about everyone listened to vinyl records, these buyers were in a position to become “tastemakers.”

You might look at a system like this and conclude that it’s archaic, crude, and certainly not “scalable.” After all, Bob Bryngelson and fans like him are one-offs – people who bought an album and have spent time with it. There’s no data or algorithm at work there.

But what it did provide was a window into the mindset of the audience. Lee told me the cards became a reliable way to determine whether an “artist’s buyers were our listeners.” The system also made it possible to identify people who developed a track record for picking hits from the album.

And it spoke to the need of programmers to find a way to tap into the hearts and souls of consumers, even if the had to resort to nontraditional ways of doing it.

of doing it.

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, I wonder whether yesterday’s programmers actually had a better bead on music tastes, thanks to analog tools like vinyl records, turntables, and little cards at record stores.

Will new music find its footing, post-pandemic?

Will radio programmers develop new and better ways to track tastes and consumption?

Is this return to vinyl just a momentary blip on the musical radar screen?

Stay tuned.

You can learn more about Lee Abrams and what he’s thinking about here.

- I Read The (Local) News Today, Oh Boy! - April 15, 2025

- Radio, Now What? - April 14, 2025

- The Hazards Of Duke - April 11, 2025

Interesting you bring up oldies, Fred. In my first radio job in 1974, I worked for a station with an incredible record library.I asked the GM, “Gee…would it be great to develop a format built around all this great music from the 50’s and 60’s?” I was told all of the music was burned out and nobody wanted to listen to them anymore. When I was asked to program what was arguably, the first “Classic Hits” station in 1998, the naysayers said the same thing about 80’s music. That’s how I figured it would work.

The truly great stuff finds a way to endure. But as Tammie Toren reminds us, you have to wonder where that next generation what will eventually be called “oldies” will come from. Clearly, a big part of the appeal of Oldies and Classic Rock is that we were ALL listening to it. That lack of communal consumption of music makes me wonder whether it can ever happen again.

I’m going to give you my take from a Gen X perspective. “Boomers” have been in charge for a long long long time. The ability of this demo to hold on to it’s dominance for so long is quite astonishing. I rack it up to the sheer numbers of the boomer generation, and their ability to (for lack of a better term) push people around. Boomers have been out of the sweet spot for awhile, and here we are talking about their music being the best music AGAIN and their way of listening to music as the best way AGAIN.

Let me be clear, Classic Rock is in a class all it’s own and I believe it will ALWAYS be that way. It was a magical time in making and consuming music. The quality and innovation FOR THE TIME is amazing. I hate to be the one to ALWAYS say this, (Ok, no I don’t), this music is an OLDIE now. You can argue and pitch a fit because it’s the best, bla bla bla. But it’s time to move over Grandpa. The Stones are cool, but so are the Foo Fighters. Van Halen will always rule, so will Disturbed. It’s not bad, it’s just different.

As for research, I agree, something has to be done. I’m probably wrong saying this, and if I am, please educate me, but a PPM is NO WAY to judge a song. Use it for TSL and CUME. It’s an amazing tool that way, but for actual music research? OMG, I can’t stress this enough, they may not be turning off your station, they may be leaving a business that’s playing your station. They may LOVE the song that’s on, but they have to leave. However, in PPM land, that gives it a lower M score, so we won’t be playing “Billy Jean” in the next update. Same thing goes for downloads… BTS fans are incredible. But does that constitute airplay for the masses, or for the BTS fans? And FINALLY, back to airplay monitors and PPM, even I know, way over here in MT that I Heart has booked Glass Animals for the Jingle Ball or something. They have a BIG REACH as far as airplay, so they’re pushing that band. For THEIR promotion. Instead of taking that into consideration, we’ve added them back to rotation because “They’re peaking again”.

We’re finding that some of the new go to research is shaky at best. Maybe we go back to ACTUAL AIRPLAY, like with Media Base, and sales, ALONG with downloads etc to determine airplay. Some people in my company have a real problem with Media Base. Maybe I’m naïve, but I still prefer to see actual spins. There has to be a way to balance airplay, on-line consumption and the like.

People are still “getting into a band”. They just do it differently. The days of someone listening to every track of every album in their basement with 5 friends are over. There will always be the die-hards, but consumption has changed.

On vinyl making a comeback, records are cool. They’ll always be cool and there will always be some kind of market for them.

OK, Tammie, I promise NOT to take that Grandpa remark personally. 🙂

I totally get your frustration, and probably express my thoughts on where the next generation will/won’t come from in my response to Kevin Fodor. It’s not just that Classic Rock (OK, some of it) is great music – it was heard by a huge generation of teens in real time in the same place – on the radio.

And there were ALBUMS, a format that engendered loyalty to bands. Sure, hit singles were important. But when you bought the LP, you discovered an artist with depth (or maybe a one-hit wonder). That’s another condition that just exist today.

We’re in a long tail world. Everyone makes their personal playlists, and exposure is splintered across dozens of outlets. It’s hard to build consensus in this environment.

And then there’s the ratings. It’s not PPM nor is it a diary. It’s having to create products lots of people like, given the conditions I just described.

I think about this a LOT (as you know), plus I get to write about it. But I most certainly don’t have the answers. I know “the next big thing” won’t sound anything like any of the big things that came before it. And that’s what keeps me hopeful.

Thanks, as always, for sharing your thoughts with us.

Some thoughts in no particular order:

1) There is plenty of new music listening going on, its just not in any kind of rock. Olivia Rodrigo released an album this year that has gotten roughly 5 billion plays on Spotify alone. Taylor Swift’s rerecord has gotten 500 million plays, Morgan Wallen’s 2021 album is up to about 1.5 billion plays and The Weeknd’s Moth to a Flame single has gotten almost 150 million. These are sobering numbers and put the 32,000 copies of that Paul McCartney album into perspective.

2) Artists didn’t release as much new music during the pandemic because they couldn’t tour to support it. And as has been noted here, artists make most of their money from concerts and merch, not selling recorded music in any format. An artist I like titled an album they released this year “Untourable Album” as a homage to that.

3) What constitutes a hit isn’t album sales or radio airplay anymore. The more people listen to a song, the bigger hit it is – that’s the only metric that matters. It can test or not – but if its being played over and over on the streamers it’s a hit. And a lot of really popular music never gets radio airplay.

4) The way people used to listen to music just isn’t relevant anymore. We can be as nostalgic as we want about sitting in friend’s basements tracking albums, but people don’t do that in 2021. And I wonder if they did just because playing one song at a time from different records was too hard – especially if you were in some sort of altered state, which was the only way a lot of those deep tracks were listenable.

5) Aside from the big stars, there are so many artists that get 10-50 million Spotify spins when they release an album. Separately, they don’t mean that much stacked up against Adele, but as a category, they probably represent the bulk of the new music listening.

6) Despite what they say in perceptual research, people are looking less and less to radio and radio formats for new music. Just compare the ratings to the numbers from the streaming services. With some exceptions, radio is evolving out of the new music business. There are a lot of reasons for that, but one of the biggest is that radio doesn’t like to program to the people who listen to most of it.

7) Classic Rock is great music and endures as a format, but it would be a mistake to think that it’s out dueling new music. Oldies formats aside, nostalgia is bad for radio. To borrow from a book that was popular when people listened to whole albums, it would do better to ‘Be Here Now”.

Bob, this is a wonderful and thoughtful comment that would require a blog-length response on my part. And the gas is running out on my 2021 tank.

I do, however, want to address a couple of the great points you’ve made here. You are right, of course, that it’s about streams and spins in the new music economy. Problem is that unless you’re Morgan Wallen, Adele, the Foo Fighters, or Taylor Swift, the payout is relatively paltry for artists down the pyramid.

You are right that artists didn’t release much new music during the pandemic, especially 2020 – the lockdown year. And don’t you think that in retrospect, it was a tragic strategic mistake? Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney+ and the other VOD services doubled down on new content, based on the premise people would be stuck at home looking for something to do. Music is just another form of entertainment that could have accompanied the pandemic (including music videos and performances), but so many artists took a wait & see approach to the pandemic. Two years later, they still aren’t touring (like they used to), and the opportunity to build a stronger fan base has passed.

I agree with your #6 point. There’s a shift in what audiences want/expect from radio. Broadcasters who believe in new music-ish formats would do well to conduct research that goes beyond “What’s your favorite station?” to investigate changing consumer needs.

Finally, the Classic Rock question. You’re right. No one bought the new McCartney album, nor was it especially a streaming success. Paul’s original group, however, had a pretty damn good year, from catalogue sales/streams to the “Get Back” trilogy on Disney+ As a producer of new music, Sir Paul is on life support. But as one of the remaining members of the Beatles who still has “it,” he will make more money than most of those on the new music charts in 2021 (or 2022).

And that brings into focus the so-called duel between catalog stations and new music stations. Nostalgia may ultimately be bad for radio IF it can’t find a way to get its new music shit together. But yet another round of fall book ratings points to nostalgia – especially during COVID – as being just what millions of Americans needed.

Well, Bob, you’ve stimulated another lengthy response from me. And I so appreciate you continuing to push me and JacoBLOG readers to see it all from another POV. HNY to you and yours.

I’m almost 66 but I still play and have a band so I guess the music we do can be called new music well the problem is if before we have a wall made of majors and publishers and empresarios now we don’t have many space to give us airplane at no airplay anyway if you want to know how we changed in 44 years please accept accident no a c i d e n t e .AC and listen how our sound changes throughout the times but of course watch we play is not classic ro