One of the themes common to major media brands is their new-found enthusiasm to branch out onto other platforms, by creating new content or repurposing existing programming. Audio has become one of the most popular sectors, especially podcasts. Most TV networks, news organizations, and celebrities themselves have tried their hand at producing and creating podcasts, leveraging their best-known talent.

As we discussed before on this blog, the irony is that the original audio medium – radio –- has generally struggled with podcasts. It’s been an ongoing conversation at our panels, sessions, and keynotes at Podcast Movement and other media gatherings.

The exception, of course, is public radio. NPR has generally led the way, but other network and entities have experienced massive success in this space, too. PRX, APM, WNYC, and other organizations have produced award-winning podcasts. And at the local level, many public radio stations have produced impressive shows and series, often revolving around important issues. To this day, many of the most successful podcasts have a public radio imprint on them.

In the bigger picture of overall listenership, most pubic radio stations have enjoyed a nice run over the last few years. The much talked-about “Trump Bump” featured an extended period where the news cycle was like a fire hydrant, spewing out one “breaking news” headline after another. But many media outlets have struggled with how to retain some semblance of objectivity in the Fake News Era. Many have failed, losing important credibility turf along the way.

the news cycle was like a fire hydrant, spewing out one “breaking news” headline after another. But many media outlets have struggled with how to retain some semblance of objectivity in the Fake News Era. Many have failed, losing important credibility turf along the way.

But one outlet that has generally walked that precarious fine line has been NPR specifically, and public radio in general.

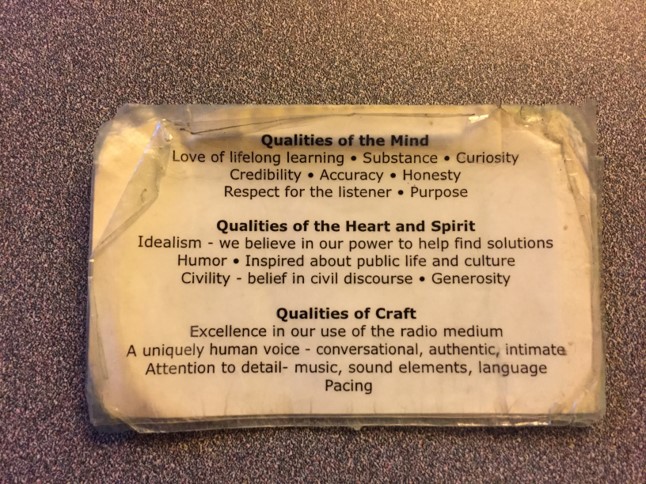

Much of that may be due to the foundation the platform first laid back in the 1970s. At one point, the Public Radio Program Directors association laminated wallet-sized cards for each reference.

Public radio has been guided for decades by this set of immutable core values that to this day, every producer, reporter, and anchor can recite.

been guided for decades by this set of immutable core values that to this day, every producer, reporter, and anchor can recite.

These guideposts have helped build brand trust – a rarity in the media business. While commercial radio offers up its All News and News/Talk formats, especially in the biggest markets, public radio stations are heads and shoulders above them. There are exceptions – WTOP is probably the best in breed, but an outlier to be sure.

While stations like WCBS-AM, KNX, and WBBM provide their services by their famous news clocks, they are largely utilities. In those same markets, WNYC, KPCC, and WBEZ provide perspective and substance – attributes seldom heard on the radio airwaves.

So, do public radio’s NPR News stations truly face any serious challenge from other radio competitors? Not really.

Instead, the pressure is now coming from another worthy player outside the radio universe:

The New York Times

Newspapers may be hurting, but The Times is the exception. They committed to digital long before it became de rigueur in the newspaper business. Not every decision by their brain trust has paid off, but in the main, they have transformed themselves into a digital dynamo, earning boxcars of cash on their non-print business.

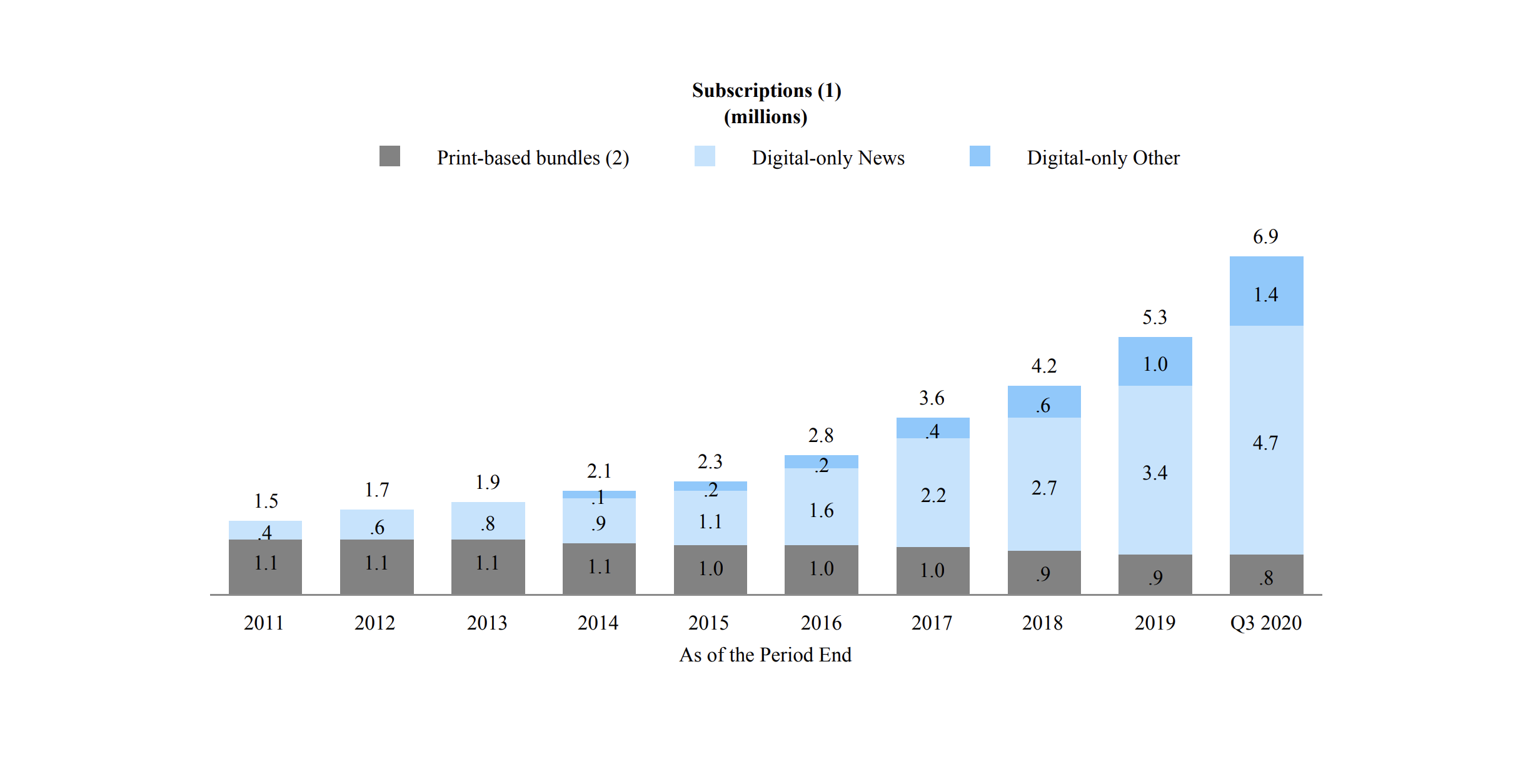

The chart below from their own earnings reports (covered by Nieman Lab) shows you all you need to know about what changing your business model looks like. The grey bars are print – the blue bar, digital subscriptions. You can see it for yourself:

Note the “Digital-only other” – the darker blue bars. The Times has created immensely popular “side hustles,” leveraging their brand and their readership’s interest in both cooking (yes, they’ve been publishing recipes longer than any of us have been alive), as well as puzzles and games, mobile activities that help us kill time while keeping our brains engaged. This category nearly doubled print subscriptions.

In case you’re wondering, more than 88% of The Times’ subscription revenue is now virtual (as of Q3 2020).

In a word, “Wow.”

But it’s The Times’ growing commitment to audio that should keep the public radio brass awake during these increasingly chillier nights. In just the past few years, The Times has gone all in, investing heavily in audio assets – programs, content, and people – especially in the popular and highly profitable podcasting arena.

But it’s The Times’ growing commitment to audio that should keep the public radio brass awake during these increasingly chillier nights. In just the past few years, The Times has gone all in, investing heavily in audio assets – programs, content, and people – especially in the popular and highly profitable podcasting arena.

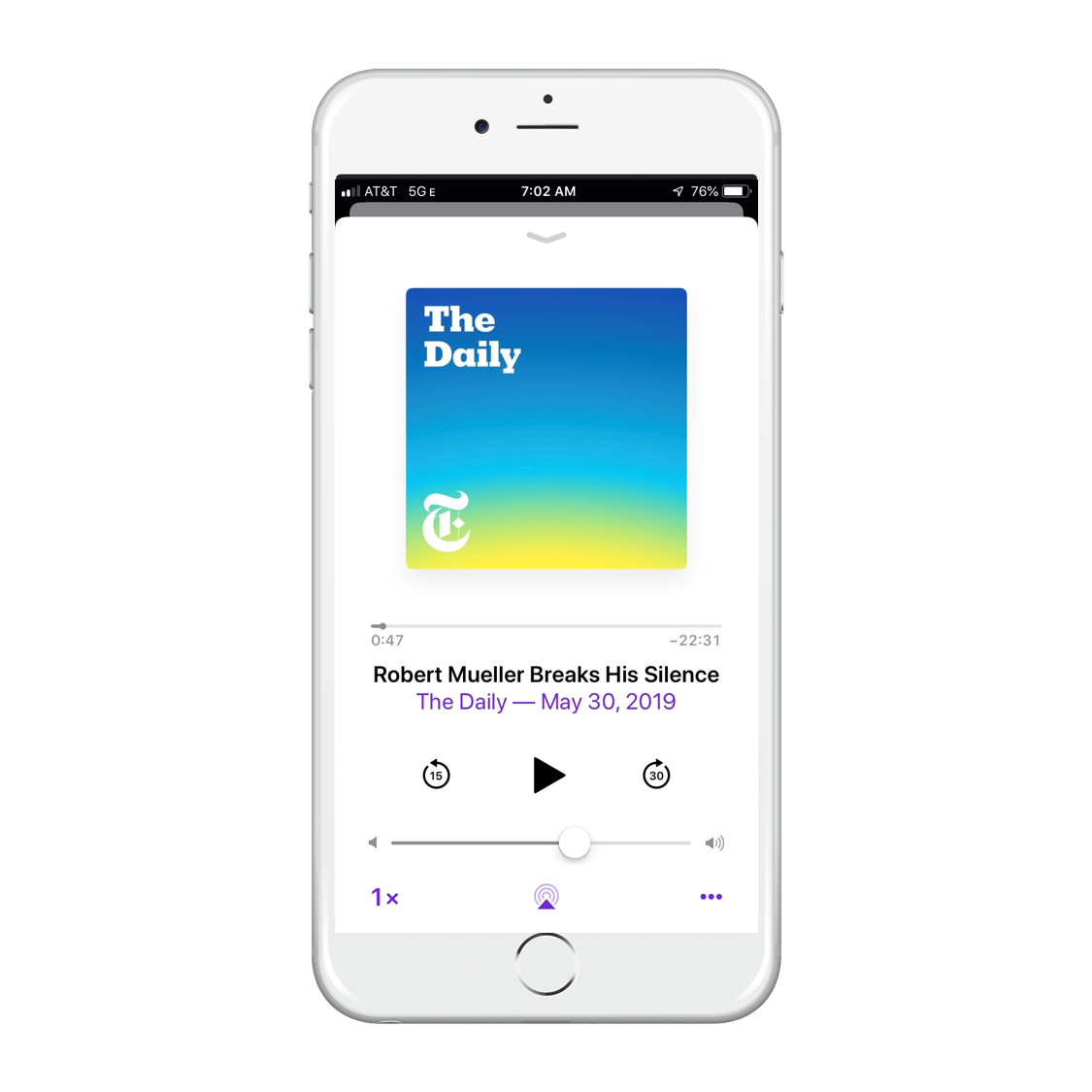

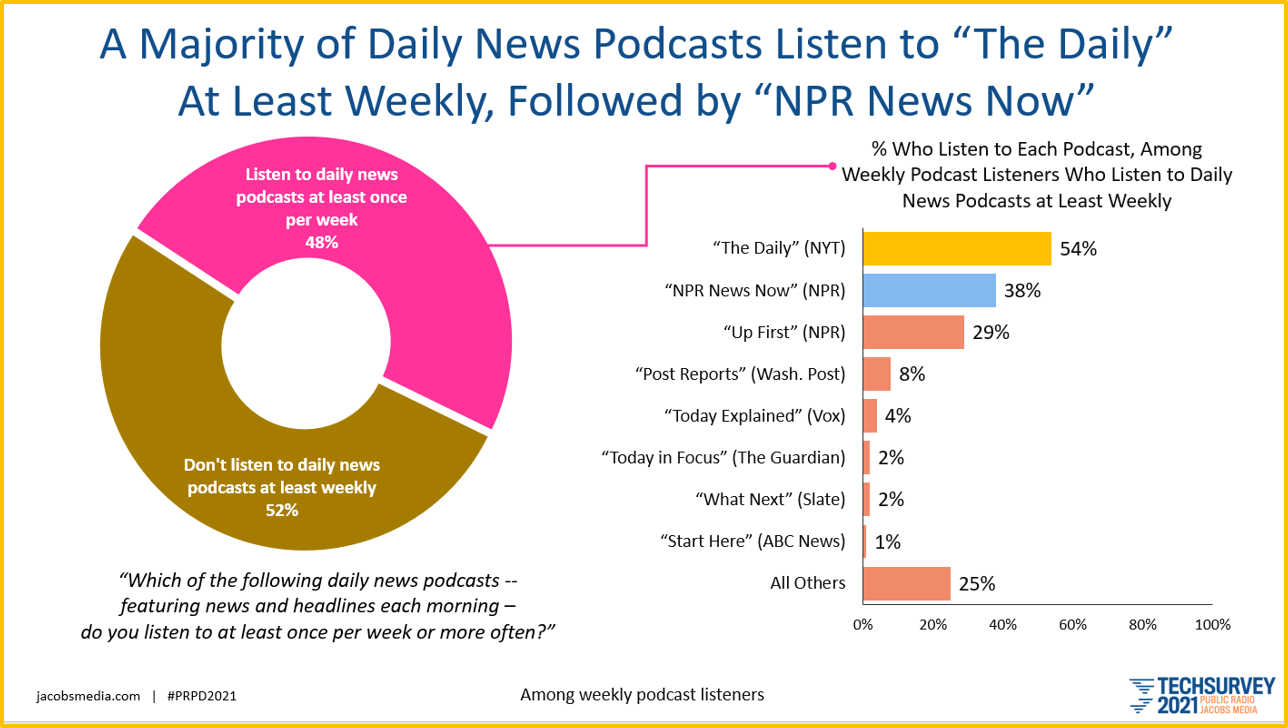

Their weekday morning news podcast, The Daily, has enjoyed huge success. In our recently released Public Radio Techsurvey, we learned that more than four in ten public radio fans regularly listen to one of these podcast productions weekly or more often.

And the winner, The Daily, by a wide margin over NPR’s productions.

The Daily launched in January 2017, and hasn’t looked back. According to Neiman Lab’s Sarah Scire, The Daily sports 4 million downloads a day. Interestingly, it became a syndicated radio show in 2018 from NPR competitor, American Public Media.

You might also recall how The Times purchased both Serial Productions (This American Life, Serial), as well as Audm last year. You know about Serial – it’s the Peabody Award-winning podcast that jumpstarted the entire space back in 2014.

Serial – it’s the Peabody Award-winning podcast that jumpstarted the entire space back in 2014.

It’s incalculable to determine just how many consumers discovered their love for podcasts when they checked out Serial. But suffice it to say, this “true crime” podcast was the catalyst that launched this new “golden age” for these on-demand shows.

The Times also bought Audm, an app that works with publishers that include The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Wired, Vanity Fair, ProPublica, and Rolling Stone. Famous narrators read long-form stories from these respected magazines, published in on-demand form.

It is interesting that in recent years, print publications like many just named have committed to video treatment of stories and features they cover. But audio versions? Not so much.

And now The New York Times is looking at this space, and thinking there’s room for a standalone audio app containing all its assets. Bloomberg quoted Sam Dolnick, a Times exec, who reveals the game plan’s simple, but ambitious goal:

“We hope this becomes a hub of audio journalism.”

Former GM of St. Louis Public Radio, Tim Eby, has a wonderful newsletter, “Three Things,” on the Substack platform. In last week’s edition, he catalogued many of these moves by The Times, concluding this:

“When it comes to audio distribution, particularly with on-demand, public radio needs to come together in a similar fashion with urgency and focus.”

So, where can you download this new audio innovation app from The New York Times? Right now, it’s in beta, only available by invitation. You fill out a lengthy questionnaire that asks in detail about your content consumption, especially podcasts. And as you’d expect, there are questions that directly ask about your use of NPR programming.

The language they’re using telegraphs where they hope to find a new crop of audio consumers:

“Journalism” and “storytelling” – two keywords that have a ring of familiarity to public radio professionals.

I’ve applied to beta the app, and I’ll let you know if I am selected.

Finally, there’s the talent piece. In 2020, The Times hired Ezra Klein, co-founder of Vox. And late last month, they poached Lulu Garcia-Navarro, one of NPR’s popular journalists, and host of the “Weekend Edition Sunday,” as well as their Up First Podcast.

In fact, The Daily team revels in just how many public radio ex-pats now produce the radio show version – now on 250 public radio stations, generating a weekly cume of more than 2 million listeners. In a newsletter story that launched The Daily radio show, ex-NPRer Theo Balcomb made this boast about the staff:

“Our founding team is full of former public radio folks.”

Sounds like a Randy Michaels claim, but instead, Theo formerly worked for NPR’s All Things Considered before switching alliances to The New York Times.

Late last month, here’s how Lulu Garcia-Navarro broke her personal/professional news:

🪅 Some news from me: I am heading to @nytopinion and I am thrilled to open up a new chapter doing what I love: telling real stories about people and how they move in the world and why they think the way they do.

— Lulu (@lourdesgnavarro) September 30, 2021

You carnivores in commercial radio reading this post would likely tell your public radio friends that these “clues” point to one big thing:

The New York Times is going right down NPR’s (and by extension, public radio’s) throat.

In other words, they want to eat public radio’s lunch. Dinner and breakfast, too.

Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at The Times’ mobile strategy – as it relates to its audio initiative, as well as what it says about where this space is heading in 2021 – and beyond.

Better charge up that smartphone.

You can subscribe to Tim Eby’s brilliant newsletter here. Better yet, hire him. He’s one of the best in the business.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Fascinating, Fred. Thanks for the excellent overview. Forever we’ve heard that “competition improves the breed,” and now we will see whether it’s true.

We will indeed, John. Thanks for chiming in.

Good overview Fred! Tim Eby’s right. And, I don’t think there will be an “on/off”, or “black/white”, or “do or don’t” solution. The APM partnership with the Times was early with the notion that a great podcast could actually become a radio show. Imagine how the NPR content and distribution team viewed THAT partnership. (I’d love to have been a mouse in the corner of that room). The blurring of the platforms is now happening all over the place. And I believe we’ll continue to see what 5 years ago might have been unthinkable partnerships between stations, networks, producers, and yes newspapers that were formerly competitors-only. Look at the WBEZ & Sun-Times consolidation. (Chicago)

Tim, it’s hard to argue with any of these suppositions. Content/distribution are seriously blurring, as the cross-currents of content and distribution mesh together. And we’re expecting to see more innovative collaborations, partnerships, and acquisitions. Hold onto your hat.

Excellent explanation, Fred. Just curious, how many people would you guess NPR (not counting the individual stations) and the New York Times employee to work strictly on their digital platforms and products? As a follow-up, can you offer a guess a what point these organizations had a separate staff of more than one or two people?

Thank you for this excellent post. Tim Eby deserves the praise you gave him for “Three Things.” He is an important voice at a time when public media needs his independent perspective.

The NYT audio aspirations mean competition for NPR News on the national/international level. Competition is good thing in the world of noncommercial broadcasting. But, how much will NYT audio impact individual stations, particularly in medium and smaller markets? Many of these stations are focused on local news and information, something the NYT can’t turn into digital revenue.

Very few NPR stations make money with their digital services. Perhaps this is the time for CPB to support “noncommercial” podcasts, etc. Stations managers still talk about how Ira Glass used This American Life to launch and promote Serial.

Some great thoughts here, Ken. Thanks for participating in this conversation. Whether you’re working for a network or for a local station, there’s a lot to consider here.

I truly can’t hazard a guess on either, Andy. But I would venture that both have robust staffs that are growing. You saw the NY Times subscription data – the lion’s share is digital. And NPR’s CEO announced that 2020 would be the first year the network’s digital revenue eclipsed its broadcast billing. Both organizations are leaning into that equation.

Thanks Fred,

Even if we don’t know exactly how many, we do know that both NPR and The NYT devoted significant resources and staffs to digital content. We also know what radio did and didn’t do. It explains the successes NPR and The NYT experienced and the results of the major broadcasters.

Of that, there is no doubt, Andy. Radio took a “wait & see” approach to a tsunami of change, and now finds itself trying to come back from behind. Even harder in the middle of a pandemic.