If you’ve been in radio for more than a few years, chances are you’ve experienced some highs and lows. A sports championship in town, a rock star’s death, weather emergencies, a local scandal, and other bigger-than-life events are often challenging for radio to cover. And sometimes, they test a staff’s preparedness and professionalism.

Then there are the events that are unexpected – totally off the charts. Columbine, Sandy Hook, Orlando Pulse, and 9/11 fall into that category. In recent years, there has sadly been an abundance of domestic shootings for various reasons and by all sorts of people to a point where we’ve become dulled to these tragedies.

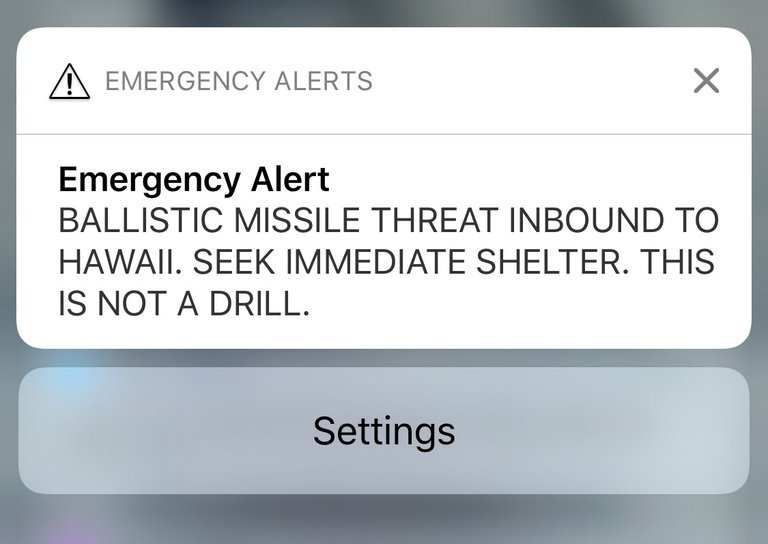

But the Hawaii false alarm nearly two weeks ago tomorrow was a true anomaly, portending a tragedy and loss of life that none of us has ever experienced. Broadcast veterans may think they’re seen it all, but a bogus text alert about a nuclear attack is off the charts, especially in the midst of North Korea and the U.S. rattling sabres and talking about who’s got the bigger button. If you were in Hawaii, the alert felt very real.

And the fact that it inconveniently occurred on a weekend morning made the emergency that much more challenging for broadcasters on the islands. You’re also looking at an event that certainly appeared to put everyone’s life in danger, including those paid to cover these types of events or board opping radio stations.

This story has been replaced during an always frenetic news cycle where there’s “Breaking News” every hour. Even the radio business has moved on. We’re now talking about Christmas station ratings and the Holiday Book, the sale of the Scripps radio group, and sluggish revenue projections.

But the nuke scare is still fresh on the minds of Hawaiian broadcasters. If you were on one of the islands at around 8am on January 13, you received that scary alert on your mobile phone. And it took a painfully long 38 minutes for it to be rescinded.

A lot can happen in 38 minutes. For a million and a half people living on a remote group of islands, it was a very real moment. Many report trying to make a cell phone call to family, friends, and loved ones, and not being able to because of overloaded cellular conditions.

But radios were working just fine, as they almost always do. As long as you owned a radio – at home, in a car, or wherever you were – you could hear the latest newest news and information about the incoming ballistic missile.

That is, if the station you tuned into was alert, at home, and properly trained for a true DEFCON 1 emergency. Much is debated every time a disaster occurs about how radio was prepared or caught napping (or voicetracking) during the mayhem.

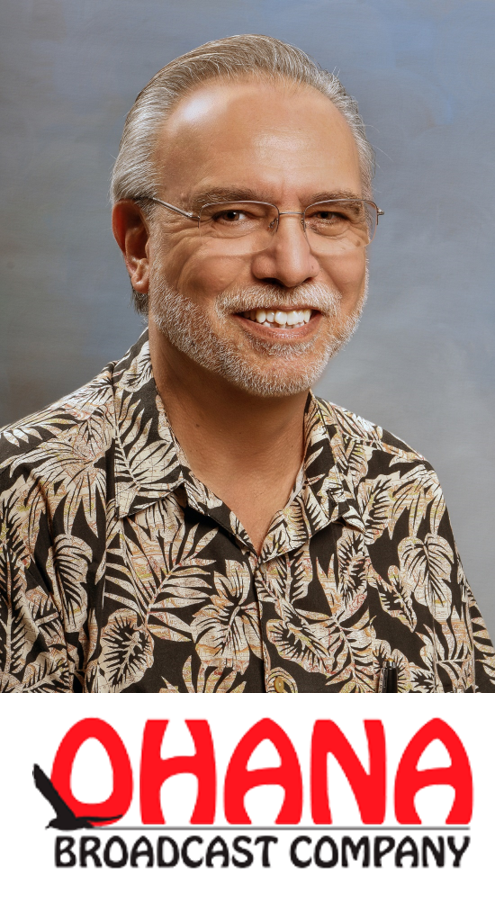

In the case of Hawaii, we don’t know the full extent of who was automated, who was live, and who was ready for this disaster. But we did connect with two market managers – Terry Gillingham – who oversees 8 music stations on the islands for Ohana Broadcasting. And we spoke to another cluster manager – let’s call him Mr. X – who preferred to remain anonymous for reasons that will soon be obvious to you.

Not surprisingly, just about every radio station was voicetracking at the time the alert broke out. But a couple of lucky breaks occurred, and there were some live bodies hanging around each manager’s facility.

Gillingham’s people had law enforcement contacts, and as he notes, everyone kept a “cool head.” In the case of the other company, Mr. X freely admits that when the alert came, panic ensued.

But both believe there’s a need to have a better plan in place. Or a plan at all.

I’ve worked with Terry before. He’s a standup, responsible broadcaster who gets it. Here’s his take:

“Have a plan in place with your airstaff. Have a backup supply of food and water . In this day and age, it may not be practical for all our stations in the building to have live attendants, but perhaps you shouldmake it a rule to always have at least one live person in the building at all times. “

Mr. X also laments that voicctracking makes stations sound “out of touch and unreachable.” He suggests the following (and he sounds a lot like Terry):

“Definitely have a plan in place, in which everyone knows their part, and what to do. Be ready – especially when tracked – to jump on your VPN and trigger a pre-produced generic message, and even break in live if you laptop has a mic.”

Gillingham noted the need for jocks and managers to be able to get on the air remotely. Given that tsunamis and hurricanes go with the territory, he knows the next disaster isn’t a question of “if” but a matter of “when.”

So, two stories – one cluster’s staff stayed relatively cool and professional. The other, not so much. Neither really had much of an emergency plan implemented or key players trained to handle a true four-alarm emergency.

And that’s the lesson for every broadcaster reading this post. Gillingham was thankful for his staff’s reaction, and admits “It was pretty damn scary there for a moment.”

And Mr. X admits his group did not offer a good response, due largely to not having a plan in place. I suspect there are many, many stations across the U.S. in the same boat.

Each has done the industry a service by transparently discussing the events of that nearly fateful day, how their stations reacted, and what they’ll do differently next time.

You have to ask yourself whether radio’s addiction to voicetracking isn’t just another accident waiting to happen when the next emergency occurs. When there’s truly no one in the building, cell service is out, and communication is nearly impossible, doesn’t Hawaii prove that luck and hope aren’t a strategy?

The next emergency – weather, local violence, or a false alarm – is inevitable whether you’re in San Francisco or Syracuse, Boston or Binghamton.

For radio broadcasters to make the claim that when disaster strikes, radio is always there is a spurious one. To be that dependable, go-to medium, the industry should step up and make a commitment to presence and training.

Everything else in radio is accompanied by off-sites, meetings, training, and seminars. Shouldn’t emergency preparedness – especially in these unpredictable, unsettling times – be one of them?

Several years ago, I was visiting a client station for a research presentation. Dinner followed, but we had to return to the station that evening to pick up our bags and check into the hotel. The ops managers walked me through the building, pointed to five empty studios playing music, and bragged that it was working seamlessly without a single live body in the building until 5 a.m. I thought of 9/11 – he was thinking of his budget.

One trained person in every building, 24/7/365 should be a mandatory requirement of holding a license. It’s not just a wise thing for communities all over America – it’s good for radio.

One trained person in every building, 24/7/365 should be a mandatory requirement of holding a license. It’s not just a wise thing for communities all over America – it’s good for radio.

Hawaii isn’t just a cautionary tale – it’s a call to action.

In Hawaiian, “laki maika’i” means “good luck.” It will take more than a lucky break the next time a near disaster strikes – especially if it occurs at night or over a weekend.

A commitment to staff and training is part of what it means to serve a community as a responsible broadcaster.

A “We will be there” stance will sell radios, it will get talked about, and it could be a key differentiator in turbulent times.

Some of you are going to tell me that I don’t understand the economics, that Q4 was abysmal, it’s impractical, or that it’s just not in the budget.

Tell that to Terry Gillingham and Mr. X. This isn’t about a one-off false alarm. This isn’t about a faraway group of islands in the Pacific that has nothing to do with you.

It’s about your station in your community.

It’s about radio.

Thanks to Seth Resler for his idea & effort for this post.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Fred, All your points and those of the two Hawaiian Broadcasters are well taken. One of the really bad parts of consolidation and the resulting huge debt is that most of the Radio industry has given up it’s position as a primary source of news and information. I say “most,” because there are still some stations that have an emergency plan and the people to execute it. Most do not. What is disheartening is that many…like the PD you quoted don’t understand and seemingly do not care. To me the caring part is our biggest loss.

Hal, I have to agree. Yes, radio is a business, and one that is under heavy pressure to make a profit. But the bugger picture suggests the medium has an opportunity to provide a unique service – one that it delivered for decades. This is what serving the community is all about.

Here! Here! In one programming job I had, I got out of bed at the sound of the weather alert radio at 1 am and drove 15 minutes to the station to get warnings on air…until my 7 to midnight jock reminded me he lived closer and didn’t mind coming in during such circumstances. The people that brag about having no bodies in a building are the last ones you’d want to call in a real emergency. The difference between a “radio person” and a “broadcaster”. At least your Mr X is rethinking things now.

Kevin, I think on Hawaii, they’re ALL rethinking things. But when the other 49 states view this as a remote one-off scare, nothing changes. Radio has an opportunity here, but it will require rethinking two decades of “cost efficiencies.”

Totally agree- broadcasters need to step up or, at least, speak up. If you talk to a First Responder about radio in a crisis, you have a good chance of getting a negative response because they’ve seen the ball dropped too often. The result? They’re taking what they see as the easier way out, using social media and cellular and hoping we catch it….and then the cell system gets overwhelmed, the power goes out, etc. etc..The EAS system runs downhill and, if the Primary is asleep at the switch, nothing happens. Good radio stations are set up for emergencies but someone has to be at home – and know what they’re doing – we have to get a lot of us back in the game.

Tom, so right. And it’s sad to see social media taking a lead role when radio owned this position for decades and decades. It’s an opportunity in a world that becomes more uncertain every day. Thanks for the note.