Back in the 70s when I got my first “radio job” doing audience research for Frank Magid in Marion, Iowa, they were the only company of their kind conducting audience research for radio and TV stations. This was an embryonic time for research. There was no music research to speak of. And most of the projects we engaged in were “in-home” research studies.

That’s right. Interviewers literally plotted out zip codes and neighborhoods, conducting research in people’s homes. Oftentimes, the questionnaires were one hour (or more) in length. And respondents were not compensated for their time. There were usually 300, 400, or 500 interviews per survey so they took time to complete.

All of that is hard to imagine nowadays when we’re oversaturated with audience research surveys and polls from just about every brand we do business with, along with others that would love to strike a relationship with us. Back then, people were eager to engage in research. The challenge was whether we were able to develop sampling techniques and methodologies capable of changing with the times.

That’s the period when call-out, auditorium tests, and even phone studies all blossomed at about the same time. They were fast, efficient, and affordable so that hundreds and hundreds of stations could afford it for their local markets.

That was then. This is now.

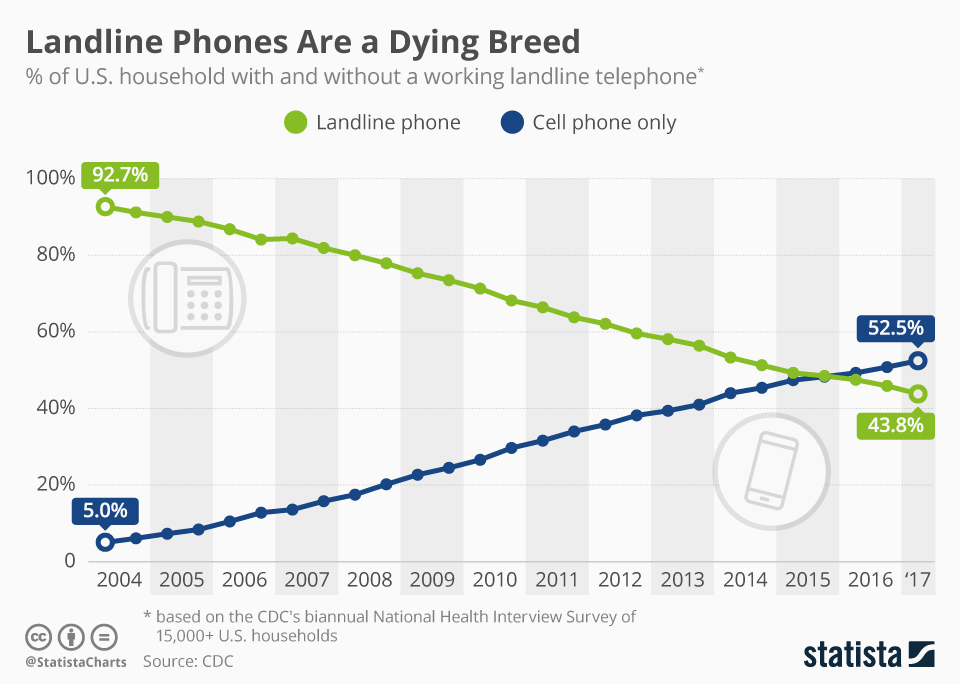

We’re at another inflection point in audience research. And this time around, it’s about the tech culture change that is all around us. We all carry cell phones now. Most of them are smartphones. And as they’ve become increasingly popular, landlines have been systematically disappearing.

The chart below from the Center For Disease Control (yes, they been tracking this for years) shows the line was crossed in 2015. That’s when “cell phone only” U.S. household passed landline homes. And the trajectories on both of these lines are clear.

Of course, this has implications on many research methodologies and surveys. The ones that have been reliant on someone answering their home phone line are on the endangered research list.

Add to that the growing number of people who simply have stopped answering their phones altogether. It may have started with their landlines, but these days, more and more people are simply not answering their smartphones. If it is apparent the call is from an unknown (or untrusted) source, it goes to voicemail – period.

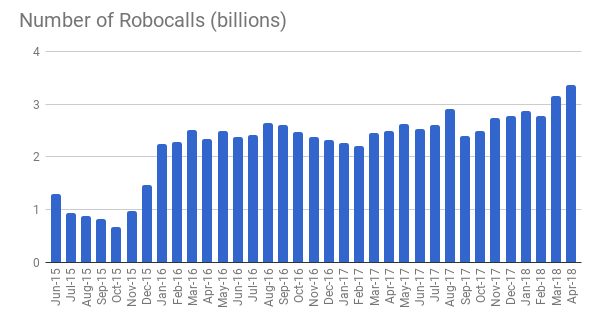

Part of the reason is the growing number of telemarketers clogging up our phones lines, not to mention the explosion of robocalls – those automated nuisances consumers will do virtually anything to avoid, whether the message is political or a sales come-on.

For researchers dependent on a phone being answered as the communications gateway to a research survey of some kind, this is bad news. But it is certainly not a surprise. It’s been brewing for more than a decade. And in the last three years, robocalls have virtually tripled, annoying millions of consumers who have become less and less inclined to say “hello.”

Last spring, The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal wrote a story that says it all: “Why No One Answers Their Phone Anymore.” He tracks the telephone mindset where a ring once meant you had to stop whatever it was you were doing to take a call.

So, what changed?

Madrigal writes that new forms of communication have become more popular, more interactive, and for many, even recreational:

“Texting is fun, lightly asynchronous, and possible to do with many people simultaneously. It’s almost as immediate as a phone call, but not quite. You’ve got your Twitter, your Facebook, your work Slack, your email, FaceTimes incoming from family members. So many little dings have begun to make the rings obsolete.”

The ways in which we communicate with one another have radically changed in just one decade.

The ways in which we conduct research need to change, too.

Of course, that mindset applies to ratings, political polls, music research, and radio’s perceptual studies. In the case of Nielsen, the powers-that-be at the previous ratings giant, Arbitron, actively investigated the smartphone – rather than the meter – as the main data gathering tool. After all, who wants to carry two devices around?

For myriad reasons, the smartphone never replaced the diary or the PPM. But all that was in another lifetime. Today, we not only carry a smartphone everywhere – including to bed – many of us are walking around with a smartwatch, a fitness band, and wireless earbuds wherever we go. The technology exists to rethink the way radio – and other media are measured – at a time when rating companies need to take all audio sources, gadgets, and platforms into account.

In just a few short weeks, we’ll debut our new Techsurvey 2019. This year, 500+ radio stations contributed more than 50,000 respondents to what has become the biggest research study of its kind in the world. And I’m proud to tell you that not a single phone call was made to gather this mountain of data. (Although many surveys were taken by someone using a smartphone.)

When we first started this research initiative for radio back in 2005, smartphones were not widely popular, few people sent text messages, and social media was embryonic. There were no smart speakers or tablets, and Netflix was mailing DVDs in red envelopes.

And back then, he idea of a “web poll” was actually pretty radical. And it certainly was criticized by research purists and other mavens, machers, and know-it-alls who were bound and determined to stay tethered to landlines in spite of the fact the world was already moving rapidly toward a state of constant change.

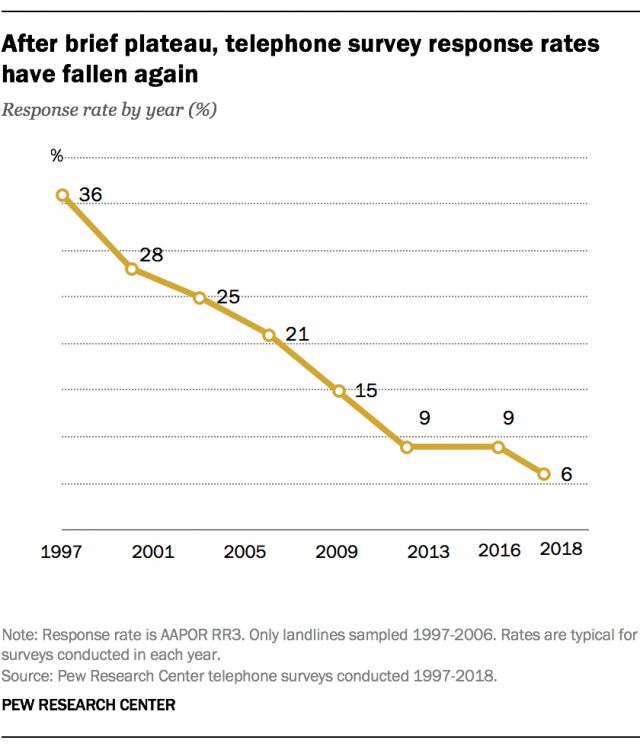

One of the most respected research organizations in the world – Pew – has been giving the survey research dilemma more than casual thought over these past few years They live and die by the accuracy and efficacy of their research. And of course, it starts with their sampling.

Last month, they published a horrifying chart that underscores the tenuousness of telephone research – crashing response rates. In fact, it won’t be long before interest rates are higher than telephone response rates. As Chubby Checker was fond of saying, “How LOW can you go?”

And Pew Research also issued issued a lengthy new FactTank report that speaks volume about where the research puck has moved:

“What our transition to online polling means for decades of phone survey trends”

Written by two high-level research execs, Courtney Kennedy and Claudia Deane, the report takes a step-by-step approach to explain why the majority of Pew’s polling is now taking place online.

And they note, the traditional research community has struggled to get its collective “left brain” around the fact the world has changed – and research must change, too:

“It has taken survey researchers some time to adapt to the idea of online surveys, but a quick look at the public polls on an issue like presidential approval reveals a landscape now dominated by online polls rather than phone polls.”

But change they must.

I’m more than aware our Techsurveys have multiple limitations. They don’t reflect those who don’t listen to radio, respondents must opt-in in order to participate, and they very likely represent a more core radio audience because of their membership in email databases, as well as their propensity to engage socially with radio stations.

And I’ve clearly pointed these caveats out for 14 years, as we will do once again later this month. I’m comfortable in the notion that every research methodology is flawed, in one way or another. None is perfect, and there is no “right way” to find out what people are thinking.

And I’ve clearly pointed these caveats out for 14 years, as we will do once again later this month. I’m comfortable in the notion that every research methodology is flawed, in one way or another. None is perfect, and there is no “right way” to find out what people are thinking.

If you take the time to read the entire Pew Research paper (and if you rely on data to program or market your station – or you’re a station owner, you should), you’ll get a credible walk-through of the trek they’ve made to arrive at their conclusion that online isn’t the future, it’s the “present” of audience research.

All of us at Jacobs Media are thrilled with the data we have to show you. Some of it will very nicely track along with past studies, as well as other research you’ve seen. But other new findings will open your eyes, change your thinking, and even blow your mind.

I’ll present the “stakeholder survey” on March 26th, and then two days later, a special pull-out for Joel Denver and Sat Bisla’s “Worldwide Radio Summit.”

And when you see the data, you might even say,

“Hold the phone!”

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

Superb and highly informative article! The shape of things to come………

Thank you for your insights!

Tony

Appreciate that, Tony.

This past election period, I participated in doing phone calling for a candidate I was supporting for Congress. In 90-minutes of making calls, about 4 or 5 of my calls were actually answered. A couple of the answered calls were by people who were angry about being called and asked to be taken off the call list. I found the whole ordeal a big waste of time.

But then I thought, I never answer any calls that come into my smartphone that are not from someone in my contact book. I let them go to voice mail. If they don’t leave a message, I block that number from calling me again.

I’ve been a cellphone household for nearly 20 years now and I cut the cord (cable TV) two years ago.

The future we talked about is really now the present.

Another FABULOUS article Fred.

Many thanks, Dick. Much appreciated!

Excellent article. Are you finding more companies are using IPSOS, NPD, and other syndicated panel-type research?

In the radio world, I would say no. But perhaps blog readers will chime in.

I look forward to seeing TechSurvey 2019 pointing toward what’s “right” with broadcasting these days, since there seems to be no shortage of opinion telling us what’s supposedly “wrong” with it.

Jerry, it cuts both ways, of course. I’m looking forward to presenting it. Thanks for the comment and for reading our blog.