It’s the scary season, all right.

And no, I’m not talking about the arrival of All Hallows’ Eve or the debut of yet another Jamie Lee Curtis fright flick, this one creatively titled “Halloween Ends.” (Is it ever really the end for these successful franchises?)

The scary thing about right now are all the “spam” political calls many of us are receiving, especially if we’ve made the mistake of contributing money in the past. Those financial contributions have come back to haunt us in the form of campaign ads, solicitations, and other requests of our time, our money, or our votes. And then, of course, there are the relentless pollsters, trying to get a grip on a political arena roiling with division and acrimony.

As an engaged American – and a research guy – I get it. Political campaigns are like death and taxes – inevitabilities we cannot escape. You can’t fault the candidates and/or those supporting causes they believe in. Nor should you hang up on those trying to capture your opinion. As they say, they’re just doing our jobs.

And so our phones are inundated with messages. Every ring could have a frightening result – if we’re crazy enough to actually answer our precious smartphones to chance a horrific outcome – or perhaps a restaurant confirming a reservation. But to what degree are we actually pushing that button and saying “Hello?”

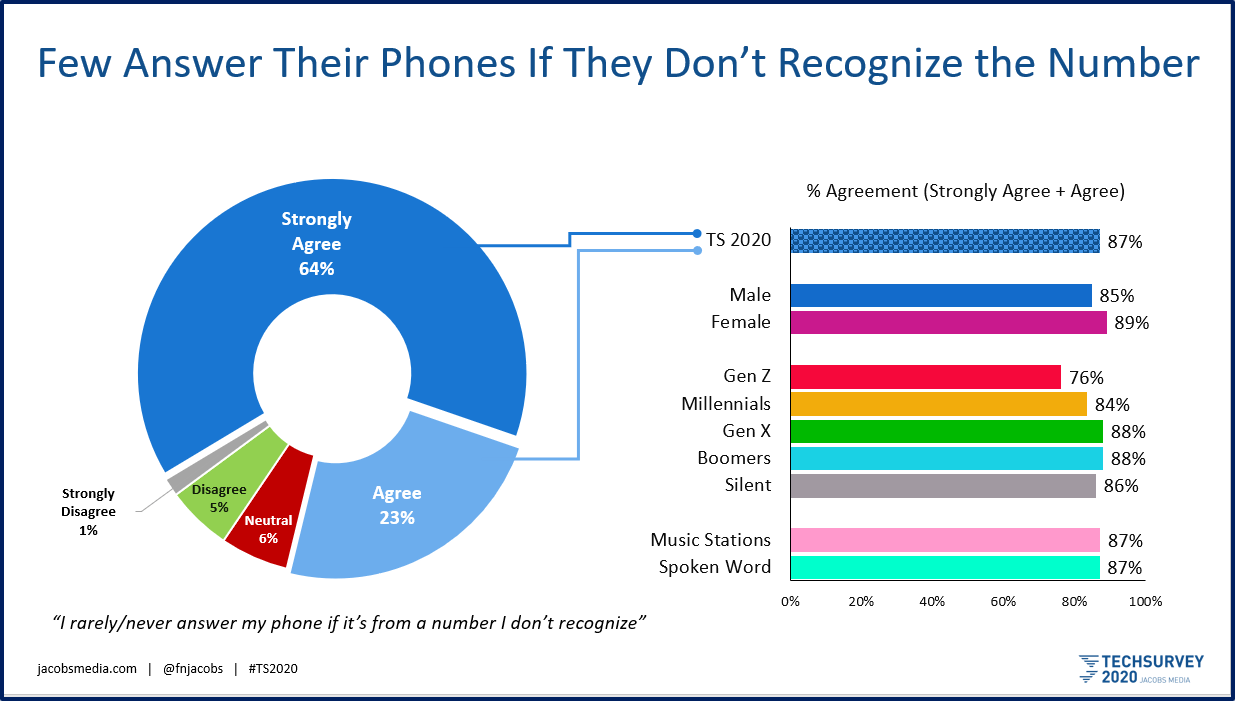

To find out, we actually included an agree/disagree statement back in Techsurvey 2020, fielded just before the COVID outbreak:

“I rarely/never answer my phone if it’s from a number I don’t recognize”

And nearly nine in ten agreed with that sentiment. In fact, nearly two-thirds strongly agree.

So what does that mean? From a human connection standpoint, a lot of us are getting voicemail because so few actually answer their phones. If we’ve earned a place in the “address book” of the person we’re calling, our chances of actually speaking with that person improves.

But perhaps we should amend this agree/disagree statement to simply read “I rarely/never answer my phone” – period. My anecdotal experience is the younger the person, the less chance they bother responding to a ringing phone.

So, what does this mean to us in radio? First off, fewer of us are using our phones to talk – the reason they were invented in the first place. Many radio programmers and personalities tell us the volume of calls coming into the “studio lines” has steadily fallen off over the past several years. Many of us would rather text or use a messaging platform for communication.

Clearly, 9th caller contests have been waning, replaced by “text-to-win” – no safer, to be sure, but more congruent with the way consumers use their smartphones. More and more, the “open mic” feature on many apps allows listeners to record and deliver comments that are of much higher quality than a cellphone connection.

Clearly, 9th caller contests have been waning, replaced by “text-to-win” – no safer, to be sure, but more congruent with the way consumers use their smartphones. More and more, the “open mic” feature on many apps allows listeners to record and deliver comments that are of much higher quality than a cellphone connection.

And push notifications have proved to be highly actionable as a tool in which to communicate news, upcoming content, and other messaging.

For fundraising – pledge drives in public radio, “share-a-thons” in Christian radio, and fundraisers like Radiothons for organization like Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals – the phone has traditionally been a major conduit. But more and more, you’re seeing “donate” buttons show up on websites, and more importantly, on smartphones. How long before services like Venmo and Zell are deployed for fundraising, just a swipe or keystroke away?

People are using their smartphones to communicate to others – they’re just not using them to talk.

But then there’s the research issue. And apologies in advance, but the research geek in me springs into action when there’s news about surveying opinions, attitudes, and perceptions.

Not that long ago, the phone was the main conduit to talk to people, to ask them questions, to survey them.

Not anymore.

A story the other day in the New York Times crystalized the problem – it’s an audience research conundrum. And that means that with the midterms coming up, it’s a political polling nightmare.

The story’s title says it all:

“Who in the World Is Still Answering Pollsters’ Phone Calls?”

Nate Cohn is the Times’ chief political analyst, so he has a dog in this hunt. So do all of us, dependent on reliable audience feedback. And in this article, he answers those FAQs about how his surveys are conducted, who is included, and how they’re contacted.

For a current national study they have in the field with Siena College, only .4 percent of outgoing research calls are actually being answered. That’s not 4%. It’s point-4-percent.

Cohn notes we’ve been on the downslide for telephone response these past several years. And like so many things, the COVID Era may have finished off the phone as a reliable research tool. He refers to the current levels of response as “death of telephone polling” numbers. And it’s not hard to argue with this premise.

a reliable research tool. He refers to the current levels of response as “death of telephone polling” numbers. And it’s not hard to argue with this premise.

There’s also the issue of participation. Cohn alludes to the fact that even when they actually talk to the “right person” demographically, the chances of participation are slim.

We saw this in the three database studies we conducted during 2020 for commercial, public, and Christian music radio. Early in the pandemic when most of us were stuck quarantining at home, a phone call – even from a pollster or researcher – was a welcome distraction. Most people were bored out of their minds. Even telemarketers likely did well. People were open and even interested making their opinions known. In that first COVID study in late March of 2020, the responses came in fast and furious.

But the other two studies later in the year proved to be more challenging. Many radio database members were ignoring station emails or not opening them at all. We achieved decent returns, but nowhere near the levels of that March.

But the other two studies later in the year proved to be more challenging. Many radio database members were ignoring station emails or not opening them at all. We achieved decent returns, but nowhere near the levels of that March.

And today, most of the researchers you talk to admit that “agreeability” to take surveys simply hasn’t rebounded. It’s not a scientific fact, of course, but it seems like many people aren’t in the mood to answer questions, much less take a survey. They’re cranky, agitated, and not in the mood to talk about their online banking, their politics, or whether they own a smartwatch.

And that takes us back to smartphones. Cohn notes that roughly three in four calls made for the Times/Siena College survey go to cellphones.

Interestingly, most of the companies conducting radio research are using online surveys rather than taking their chances with phones. As Cohn notes, “the Times has more resources than most organizations….”

Radio company budgets are limited, and research expenditures have been cut this year for obvious economic reasons. Most of the researchers serving radio companies have gone heavily into the online survey realm where respondents can be contacted by email.

Is it perfect? Not by a longshot. Not everyone in America is online. And many rural areas, in particular, don’t have broadband access.

The Times story, however, may be more indicative of other truths. The disruption affecting our society on so many fronts, catalyzed in many cases by technology, is impacting the results of research studies. And frustration over just about everything may be spilling over into the willingness to take surveys and provide opinions.

That seems to be the case over the past few years on the political front. Pollsters have questioned whether respondents are always telling the truth when answering questions about issue and candidate preferences. What’s worse than not responding to a survey? Intentionally giving an incorrect response.

In the world of radio ratings, there’s less reason to fabricate preferences. And in the PPM world, the good news is that only audible content counts anyway. (Ironically, Arbitron didn’t start including what were known as “cell phone-only households” in their samples until 2009 or thereabouts.)

The question remains whether we’re finding the right people to take our surveys in an environment that’s not as “research friendly” as it once was.

Can we trust our research and our data?

Can we trust our research and our data?

Are the phones still a reliable way to contact people – and for them to get in touch with us?

I know many of us will be watching those midterm results very carefully for political reasons.

We should be paying attention for research reasons, too.

Did the pollsters get it right?

A JacoBLOG shoutout to Steve Goldstein. And I’m sure I’ll hear from Larry Rosin.

- 5 Lessons For Radio From The Apple Watch - May 5, 2025

- DJs And Baristas: Can They Save Their Companies? - May 2, 2025

- Radio’s New Audience Equation: Z Over Y = Trouble - May 1, 2025

In essence, it’s the axiom of statistics: “garbage in = garbage out.”

I am one of the 87 percent, Fred. If I don’t recognize the caller, I let it roll to voicemail–and my suspicion it was a robocaller/solicitor (which I call a “mosquito”) is confirmed when they leave no message. The bane of modern life. I pity the pollsters; and take their reports with rock salt.

Still have a landline, though, because so many outfits require a phone number for (usually) legitimate reasons, and I’m damned if I’m going to give my mobile number to anyone I don’t really want to talk to. (Unless it is so urgent as to necessitate synchronous communication, my friends just text anyway, so much more convenient and concise.) At about $10/month for a landline it’s a no-brainer. Your mileage may vary.

Great post, Fred. I’m in that 64% myself. My cell service comes with not only automatic blocking of known spammers, it lets me send a screening message to any unknown caller and I get a voice-to-text reply on my phone display (although 99% of the time, they just hang up … a telling statement in and of itself).

My “landline” is actually through a VoIP provider and the base unit lets me send any calls whose Caller ID has no information and whose number I don’t recognize, directly to voicemail. Again, not surprisingly, none of those leave a message. (At least the robocallers now seem to recognize the difference between a live person and a voicemail.)

That said, I believe that if an outgoing number used for station research had a Caller ID with the station call letters and/or on-air positioning brand, any listeners would be much more likely to answer the call. Like myself, they likely refuse to answer because they don’t recognize the calling number.

(Oh, as a side note: The VoIP provider allows me, via their website, to assign my own Caller ID information for any known caller that doesn’t send data themselves, and future calls from those numbers will display with the information I “attached” to them.)

That said, and perhaps you know the answer to this, Fred, is … how much research is now shifted to websites, replacing callouts? I know a lot of major market stations still do music research and I wonder how they are managing it in light of the issues you have raised here.

I believe we’ve been conditioned to not answer our phones by the glut of scam robocalls. If the “do not call” list had actually worked, and whatever existing technology to block scam calls was in place 20 years ago – we might be more receptive to picking up the phone today.