A common conversation in music circles always revolves around the state of new music. Of course, it depends on who you talk to, but many once dependable radio format genres have been in droughts for some time now.

Some point to the pandemic, and its disruptive effects – no touring, doubts about releasing new product, financial pressures trying to support staff and crew. The unpredictable nature of the past two years has taken its toll on many business sectors, but especially the music industry and its new release machinery.

There’s no shortage of head scratching in many corners of radio, and I presume, the record industry. Mavens like Guy Zapoleon and Sean Ross have offered their takes on the state of “new music.” And yet here were are – at a bizarre inflection point where nothing surprises us. What cycle are we in? Who the hell knows?

Last week, I made my stakeholder presentation for Techsurvey 2022, and next week, a different “cut” of the study will be presented at the AllAccess Audio Summit. For Techsurvey, this will be the 12 consecutive year (except for 2020 when the conference got scrapped.)

Last week, I made my stakeholder presentation for Techsurvey 2022, and next week, a different “cut” of the study will be presented at the AllAccess Audio Summit. For Techsurvey, this will be the 12 consecutive year (except for 2020 when the conference got scrapped.)

Once again this year, I’ll try to make the data talk and tell its story. It doesn’t usually take long for a narrative to emerge from the mountains of charts and graphs, and this year is no exception. And based on some of the feedback I’ve gotten from our AllAccess “sneak peaks,” I can tell you one of the storylines revolves around the perilous state of new music.

There’s a couple of data points I want to share with you – both of them trended back to years when the term “social distancing” sounded like taking a break from Facebook or Twitter. Going back several years and studying trendlines is a smart way to develop confidence in the data and what it’s trying to tell us.

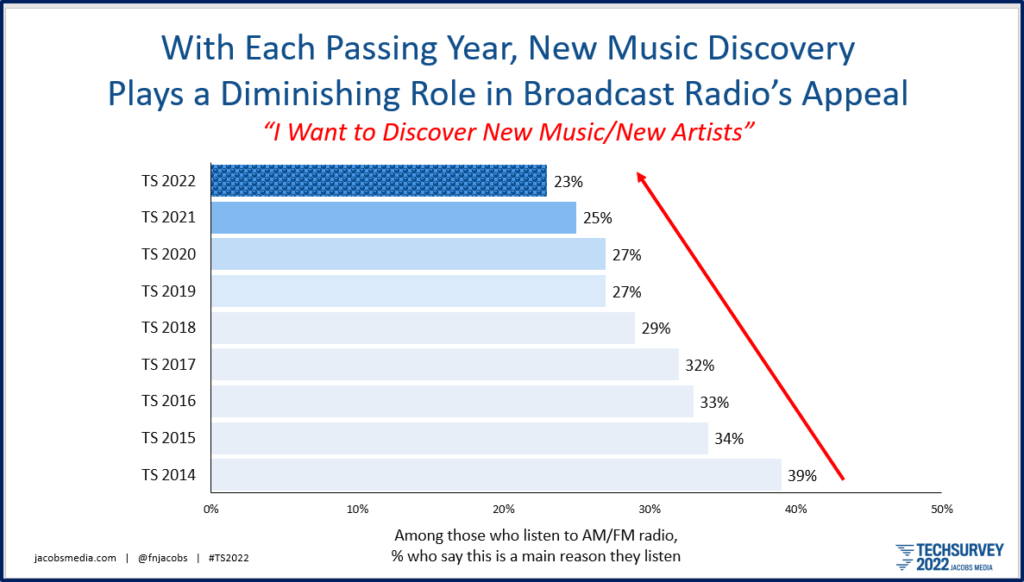

Every year, we ask the “Why Radio?” question. It’s a list of 20 or so possible broadcast radio attributes. Respondents tell us whether each is a main reason, a secondary reason, or no reason at all for listening to AM/FM radio. Near the top of the list are the “usual suspects” – personalities and music, perennially in the top 5. And then there are the more surprising positives of radio: it’s easiest to listen to in the car, and it’s free. Like clockwork, they show up near the top every year.

But the headline is that you have to go well down the list before you come to music discovery, stated as “I want to discover new music/new artists.” This year, less than one in four – 23% to be exact – say it’s a main driver for their radio listening. But this finding is nothing new. It’s been headed this way for many years now. In fact, based on the trend, it’s hard to imagine anything stopping it:

But the story doesn’t end there.

But the story doesn’t end there.

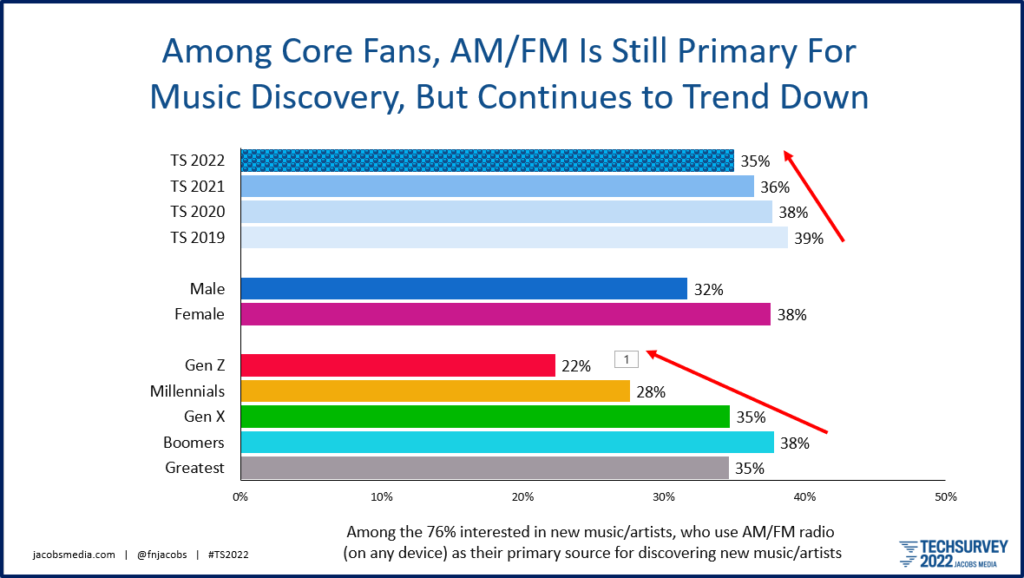

It turns out the vast majority of our respondents have interest in new music, despite our aging radio sample. In fact, three in ten say they’re especially attracted to new releases, obviously leaning young. So, the follow-up question is the obvious one:

“What is your one PRIMARY source for discovering new music/new artists?”

And among these mostly core fans of radio, their top choice is not surprisingly, AM/FM radio. But not overwhelmingly so. In fact, just over one in three (35%) goes to radio for new music discovery, another line that is trending down. And the younger the respondent (yes, the most interested in new music), the less likely they are to choose radio as their top choice to hear the new stuff.

Not a pretty picture, but one that aligns with Techsurvey’s historic narrative.

And then yesterday, a MarketWatch story comes out in their “The Margin” column. Written by Charles Passy, the title sums it up:

Passy explains that for the first time in history, Luminate CEO, Rob Jonas (pictured) points out that in the world of streaming, catalog music passed the new stuff. Jonas, whose company owns Billboard MRC who put together the report, calls it a “generational shift.”

Why is this happening?

First, Jonas points out that aging Xers and Boomers have advanced technically, now embracing streaming. And of course, younger people don’t exclusively listen to new music. Passy points out that younger consumers have plenty of interest “in the music of previous generations.”

But perhaps the biggest speed bump is the sheer number of new releases, coupled with the exponential growth of digital outlets. On the surface, this would seem like a target-rich environment for fledgling stars – more touch points where their music can be exposed.

And yet, the opposite is true. Consumers’ listening time is splintered across so many different platforms that consensus hits are a rarity. Back in the day, it may have been difficult to get a song added on the nation’s top stations. But once an artist accomplished that feat, the collective airplay from stations all over the country aided chart-climbing and hit-making. If a song was any good, and received solid radio exposure, it had an excellent chance to now be heard on Classic Hits and Classic Rock stations.

Strangely, even though radio’s star has faded over the past decade as digital has exploded, breaking new bands has become a more arduous task. Yes, top-down, corporate playlists will always be the top scapegoat, but the data suggests the problem is far more complex.

When there are multitudes of streaming outlets with little curation, most consumers are largely on their own. While there’s nothing particularly wrong with that, it’s not an environment likely to spawn national (or global) hits. When everyone’s theit own program director, you’re going to end up with a patchwork quilt where the word “hit” loses its meaning. Or what’s a hit for me is not a hit for you. Or for her. Or them.

For radio, there’s seemingly little appetite to create new music franchises. These endeavors require staffing, expertise, and they are going to inherently skew young. Broadcasters have shown absolutely no willingness to build brands that attract under 25 year-olds for fear of aggregating demos that are unsellable.

For radio, there’s seemingly little appetite to create new music franchises. These endeavors require staffing, expertise, and they are going to inherently skew young. Broadcasters have shown absolutely no willingness to build brands that attract under 25 year-olds for fear of aggregating demos that are unsellable.

And the record labels are proving they can make enormous profits on streaming older music, and buying up the catalogues of artists like Dylan, Springsteen, and Stevie Nicks. Where will future artists with enormous libraries of hit songs come from? No one’s thinking about that right now.

“The answer” is radio and records working together to cultivate artists, expose them, and build artist stables of the future – just like they used to. But given the current relationships and the financial realities of today, that’s unlikely to happen.

What’s “new?”

You tell me.

Thanks to Jeff England for the heads-up.

- Media And Technology In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - April 18, 2025

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

Hi Fred.

You correctly point out that there are multiple streaming options and little curation. However, it strikes me that the new curation is done by algorithms and Ai that deliver playlists like Release Radar on Spotify. The law of unintended consequences that our new Music Director is a series of one and zeros.

Maybe in the absence of radio taking the lead on curation, we deserve those algorithms. Great to hear from you, Rob.

Very good point

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot back in the ’80s! Local venues, record stores and radio stations all got taken over by big corporations.

The paradise of the ’50s-70s was where young artists could eke out a living while they learned how to communicate with fans on stage. They never recorded prior to learning how to actually communicate. There is as much raw talent as ever today but not nearly as much performance experience. And that’s not to mention young fan experience. Music became Muzak.

Bob, there are some smart observations here. For both radio broadcasters and musicians, the old system has its flaws. But it provided a pathway for composers and performers, as well as the benefit of radio stations being new music “discoverers.” And yes, I miss the pre-paved paradise.

Maybe the search for new “national” hits is a red herring, Fred. Perhaps radio should look instead to its unique strength in comparison to satellite radio and streaming: localism, of course. When radio was hot in my hometown, the focus was on all the local bands you could actually go to hear at local performance venues–the Fillmore Ballroom, the Avalon, the Carousel, etc–and before long this was dubbed the “San Francisco Sound.” Its national fame was inadvertent. Adventurous local PDs jumped on this and, in the then-new FM environment, they soared and left the local AM top-40 stations in the dust.

Local music is still out there! Individual curation by air talent was the early paradigm, but over the years PDs started flexing their muscles and giving stations a somewhat more consistent sound. It was still human curation, which I say will beat AI every time. Only an actual human really knows how to kiss your brain–and that’s what radio is about.

You are right, of course, John. Local is the unique flavor broadcast radio still (potentially, at least) offers. I was thinking of a scenario that could scale nationally. But your idea might ultimately be more doable. That is, if broadcasters recognized the value of discovery. I appreciate you weighing in.

What an incredibly good read, Fred! I really like that you didn’t focus on how much artists suck or what not. You hit the real problem. The pandemic and shifting in an ever changing universe.

Reading this made me feel like I was trying to find something to watch in the app driven landscape. A fellow PD and I were talking just the other day about how TOO MANY choices can actually fatigue you when choosing, so you fall into the hole of what you already know. Hence, watching Doctor Who for the 100th time instead of picking something new. Or choosing The Eagles over the new band Alexa wants you to hear. We couldn’t really see a current solution for this, as it’s only going to get to be wider. We feel the solution is a new one. Maybe we AREN’T the hit makers anymore. Maybe we’re just the hit players. Maybe making it to radio means you made it. Just throwing stuff at the wall here. It’s a good question, and it will be vexing me, and others for quite awhile.

Thank you for always giving me new ways to look at things. Have a great day, Fred!

Tammie, thanks for bringing clarity and perspective to this conversation. I think part of where we go next is a product of where we’ve been. Even though we’ve all been wrapped up in this for a long time now, putting a point on it is important. I appreciate you chiming in on this one.

Radio made a decision about who to focus on and how to do it – one of the results of that decision was the decline of its protentional to make hits. Two key issues seem to be at the heart of this:

1) Radio formats are increasingly self-limiting – by their nature, 25-54 focus and the growth of the hub and spoke programming model.

2) Music has become much more democratized thanks to streaming.

Radio isn’t the sole new music gatekeeper anymore. What do Phoebe Bridgers, Cody Jinks, Michael Buble, Arcade Fire Tyler Childers and Kurt Vile have in common? They all have songs with well over 100 million streams that never get played on radio. As people get more exposed to different music on streaming services and radio becomes increasingly narrow, it’s naturally losing its place as the primary new music discovery destination.

Streaming has made format definitions squishier and say what you will about the Spotify algorithm, it sends people songs they wouldn’t find otherwise every week. Compared to listening to a radio station, sitting through all the songs you already know/8-minute spot clusters hoping to hear a current that you haven’t before, those skippable Spotify lists are way more efficient for music discovery. Labels used to prioritize artists and songs, promote them heavily and there were ways, legal and otherwise to induce programmers to add them. The highly guarded and ever-changing Spotify algorithm just doesn’t respond to free promotions, meals, furniture and chemicals the way radio PDs did.

Some of this was inevitable as streaming emerged and grew, but some of it wasn’t. There’s a very obscure song written by a folky who had a moment 40 something years ago in LA – “Its Time to Live the Choices That We’ve Made.”

I think that question of whether this was all inevitable anyway, thanks to technology, is a good one. We’ll never know, of course. But based on my knowledge, I would answer it as “partially inevitable.” Radio could have never staved off streaming, much less the Internet. But it also could have continued being an influential force in new music discovery, and as a taste-making platform. It let advertisers dictate programming – period. And you can see where that has gotten us. Thanks, Bob, for the thoughtful comment.