There’s one thing most of the 180,000+ attendees at CES can agree on:

The event is so spread out around the Convention Center and The Strip that it’s impossible to see it all.

But there’s likely a second issue where they’re on the same page:

AI was the star of CES 2020.

Everywhere you went, it was “AI this” and “AI that.” Seemingly, every device, gadget, platform, and yes, refrigerator and microwave oven had some sort of Artificial Intelligence component.

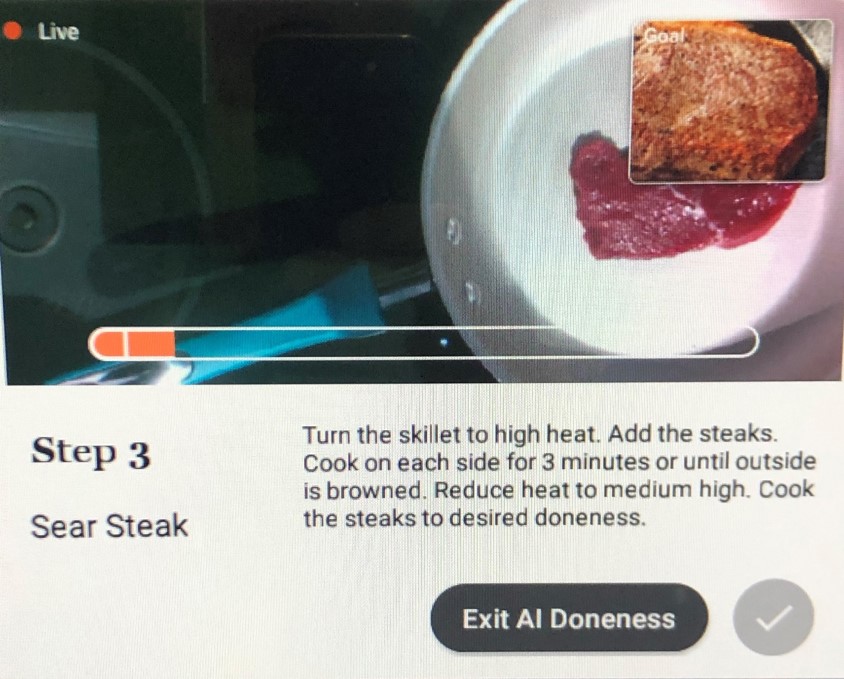

We saw a fascinating application at Haier (a massive Chinese home appliance company with a major CES presence).

We saw a fascinating application at Haier (a massive Chinese home appliance company with a major CES presence).

With technology right out of Apollo 13, you take a photo of the ingredients you have laying around, and the AI engine concocts several dishes you can make, complete with step-by-step preparation guidelines and nutritional information. (With this technology, even I could stumble my way into making something edible.)

And yet, unlike everything else we’ve become accustomed to experiencing at CES, you can’t really see AI. As one of our tour guides, Shawn DuBravac reminded us, “There’s no ‘marketplace’ for AI here at CES.”

That’s part of what makes AI so compelling and so elusive. We can’t touch it or experience it.

It just is.

And it’s now being baked into virtually every medium, gadget, app, product, and platform on display at CES. Executed well, its presence is stealth-like, below the surface, hard to detect. Like WiFi that is fast and clean, we don’t notice it as we go about our tasks. It’s just there.

Many have asked how AI is defined. The best explanation may come from the Internet Society:

“Artificial intelligence (AI) traditionally refers to an artificial creation of human-like intelligence that can learn, reason, plan, perceive, or process natural language.”

An additional element here is the ability to predict future behavior, based on the history of our past activity. This is how software, devices, and apps know our movements – where we live and work, our commuting patterns, our media and purchasing habits, and as we saw at CES, even our moods.

Maybe more than cars, smartphones, or screens, the most ubiquitous device at CES was the camera – virtually everywhere, and often trained on us – not just on the road.

Autonomous driving applications are punctuated with cameras  aimed at us – drivers AND passengers – monitoring whether we’re paying attention, we’re falling asleep, and soon, whether we appear to be happy, sad, pensive, or moody.

aimed at us – drivers AND passengers – monitoring whether we’re paying attention, we’re falling asleep, and soon, whether we appear to be happy, sad, pensive, or moody.

And while it’s not here quite yet, the ability to anticipate or interpret our moods and emotions – and serve those needs and feelings – is where AI is headed. This was evident at CES 2020, especially when you’re staring at autonomous cars and thinking about what people will do when they’re “driving” one.

That’s the essence of what the CEO of Connected Travel, Bryan Biniak, refers to as the “passenger economy.” The auto companies know there will be fewer vehicles on the road in the not-so-distant future. So, the goal is to determine how to monetize everyone riding in a vehicle – the driver and the passengers – as they travel from Point A to Point B.

We’re now seeing the impact of AI when we watch sporting events. And it will increasingly be present – like it or not – during televised games representing all sports. By measuring past performance and tendencies, intelligence engines like AWS (Amazon Web Services) and the NFL’s NGS (Next Gen Stats) increasingly are able to predict outcomes, helping us to better understand why that base got stolen, why that pass was caught in traffic, or why that layup was blocked.

In the world of media, art, and what we now call “content,” there are examples of AI springing up well outside the Las Vegas Convention Center. One of the most interesting is the entertainment conglomerate, Warner Brothers, now having its lunch eaten at the movie box office by the amazing Disney.

While Warners insists AI will be deployed to only “low-value, repetitive tasks,” it is finding its way into the marketing process. According to Slash Film, the studio will be using AI technology to advise on optimal release dates.

While Warners insists AI will be deployed to only “low-value, repetitive tasks,” it is finding its way into the marketing process. According to Slash Film, the studio will be using AI technology to advise on optimal release dates.

Powered by a company called Cinelytic, the data is apparently not being used (yet) to weigh in on the wisdom of greenlighting a project or a film. But it’s hard not to imagine how the door will one day open on AI applications at the creative level.

Maybe even in radio.

Will the bigger labels utilize AI tools on the A&R side of the business to find the next Billie Eilish or to determine which track on an album should be chosen as the first single? And down the road, perhaps a program director will use it in conjunction with music research to predict what songs will be hits – before they’re added to the playlist.

Clearly, broadcast radio’s biggest companies will have a decided data advantage over the smaller players in determining and predicting tendencies, habits, and tastes.

And if you think I’m exaggerating, consider it wasn’t that many years ago when savvy, curious stations turned to technology for music scheduling. That meant moving away from card boxes, sequence sheets, and format wheels to test drive computerized music scheduling software, first pioneered by Andy Economos at RCS.

In the early 1980’s, it was the person sitting behind the mic making the choice of the next song to play (within category parameters, of course). “Machine learning,” for all and intents and purposes, ended that era of the jock as the “selector’ of the music.

The recent cutbacks, “reductions in force,” and the “hubbing” of radio production, programming, DJs, sales, and promotions is part and parcel of the bigger move toward data and how to use it to create operational efficiencies and improved results.

![]() Radio broadcasters that don’t have “scale” (nationally, regionally, formatically) may have two ways to go. The first is to copy the moves of the big boys, utilizing data to create (hopefully) better decision-making and execution. That’s a heavy lift for a smaller company (see the Warner Bros. example) trying to duke it out with the juggernauts.

Radio broadcasters that don’t have “scale” (nationally, regionally, formatically) may have two ways to go. The first is to copy the moves of the big boys, utilizing data to create (hopefully) better decision-making and execution. That’s a heavy lift for a smaller company (see the Warner Bros. example) trying to duke it out with the juggernauts.

But the other is to keep it human, keep it real, keep it local.

Just as it was the case when music scheduling started to become the industry standard in radio programming, there was rampant abuse of the software, often out of ignorance or simply bad usage, application, and execution by PDs.

And then there’s the other approach, ultimately more expensive and “people-intensive,” especially designed to be effective at the local level. It involves people, community, networking, and a lot of heavy lifting.

The end results are unknown, of course. There are lots of moving parts to this slow and steady way to build brands and grow companies.

While all eyes were on iHeartMedia last week, Ed Levine may be one to watch. He’s the CEO of Galaxy Communications, and while many companies these past several days, weeks, and months were in the process on consolidating their operations, always the contrarian, Ed was moving in a very different direction.

During last week’s group hand-wringing session that rippled throughout the radio industry, he doubled down on his local operating philosophy, embracing Central New York and his company’s hometown approach:

But that doesn’t mean Galaxy and other agile small companies can’t and won’t use data to help guide their decision-making.

There is no one way to win. Philadelphia’s Jerry Lee (WBEB) proved that not just years, but for decades. Owners like Ed Levine, Tom Yates, and Vicky Watts are headed in a different direction.

AI is here to stay, but so is the spirit of the radio.

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

- I Read The (Local) News Today, Oh Boy! - April 15, 2025

Both exciting, and scary, Fred! But…Hmm.

I wonder if A.I. can tell when a baseball team is stealing signs?

Nice subject to bring up on National Disc Jockey day. 😉

But, everybody’s right. Or nobody. Thank you Mr. Hawking.

Mostly Jerry Lee is right. Once something catches on – we all tend to do it. Once we are ALL doing it is when it’s time to do something different. Even if that might mean going back to the way we used to do it.

As someone who’s been there and done it, I always enjoy hearing from you, Bobby.

Radio might be better off being AI’s counterbalance, than its advocate.

To some extent, radio is already behind in the race to use AI. Pandora and Spotify have spent a lot more on predictive analytics than radio has and because they aren’t limited by a finite number of radio stations in a market, they have much more potential to leverage AI into a personal experience than radio.

But they can’t be live, can’t respond to a phone call, can’t reach out one on one to a fan, can’t do a great bit built around a local issue, can’t invite you backstage to a concert, ect. It’s possible that AI might be useful in guiding radio as to which of those might be more important to each individual fan. But ultimately, radio probably isn’t the medium likely to benefit most from algorithmic input.

Your suggestion that “the ‘hubbing’ of radio production, programming, DJs, sales, and promotions is part and parcel of the bigger move toward data and how to use it to create operational efficiencies and improved results” is mostly off the mark IMO. Hubbing is all about operational efficiencies, but not at all about data or improved results. Radio has a lot less real data than it did 25 years ago and the results, whether measured in overall listening or operating profits are not by any calculation I’m aware of, improved.

What perplexes me is that radio has plenty of data that shows the live, local, personal thing as the only controllable reason that listeners cite as a key to keeping them using it, yet the industry seems hell bent on dumbing them down and/or eliminating them.

You mentioned Jerry Lee. Am I the only one to notice what’s happened to WBEB’s ratings since Jerry Lee sold it?

Bob, as always, a stimulating, thoughtful comment. I’m not suggesting that “hubbing” is an inevitable outgrowth of data – only that it’s part of the efficiencies broadcasters are seeking, often through data. You are correct that radio could be using data to illustrate relationships and attribution. And the contradiction you suggest near the end of your comment defies explanation. I think about it much of the time and have openly expressed that in this space. Thanks for helping further the conversation, as always.

A-Men! Nothing is as involving as live performance and that includes live DJs.

“… the other is to keep it human, keep it real, keep it local.” Another great one Fred. Many ways to the prize and, oif ethical, all good.. (and thanks for the very kind mention)

Earned. Thanks, Tom.

I believe personality radio, except in morning drive, was murdered by poor interpretation of good research. When listeners told us they didn’t want to hear DJ’s talking on, and on AND SAYING NOTHING, they weren’t saying they wouldn’t listen to intelligent, thoughtful, creative and entertaining Air Talent. But, dead is dead. AI is just the next step beyond totally muzzled, liner card jocks. AI is cheaper, and in today’s corporate environment, the bottom line is ALWAYS the bottom line.

Jack, it’s hard to disagree with your position here. It’s always easy to cut back and reduce. Much more difficult to create, build, and nurture personalities. The industry continues to struggle with this issue, leaving many dayparts as simply a collection of songs and playlists. Thanks for the spot-on comment.