This post is nearly a year old and is all about the changing metrics that explain human behavior when it comes to music consumption and discovery. In an industry dominated by perceptual studies, call-out research, and auditorium music tests, Spotify, Shazam, and other streaming tools are providing data the likes of which we’ve never seen before. In the process, they may be defining the way consumers discover new artists and new music. An obvious prediction for 2016 – more and more strategic decision making will use Big Data. But perhaps a key differentiator is that it won’t just be callout, auditorium tests, and perceptual studies.  In last Wednesday’s post, we talked about how music performers are faced with difficult challenges and decisions over distribution and monetization. We have used this space in past posts to discuss the way that digital data and consumption patterns are changing the relationship between artists and their music, and the fans that listen and purchase their songs and albums.

In last Wednesday’s post, we talked about how music performers are faced with difficult challenges and decisions over distribution and monetization. We have used this space in past posts to discuss the way that digital data and consumption patterns are changing the relationship between artists and their music, and the fans that listen and purchase their songs and albums.

Yet, on the radio side of the ledger, so much of how programmers, consultants, and researchers evaluate music is definitely old school. Yes, there are mechanisms in place like KKDO’s “Like/Don’t Like” voting system that provides early indicators of potentials hits or predictable stiffs. Some PDs are consulting digital services, including Shazam, YouTube, and iTunes to gain a better sense of what consumers may be up to. But for the most part, it’s the charts, music sales, callout in one form or another, and library tests. Most of this activity is simply minor variants on the way stations have evaluated music and deciphered data for decades.

Yet, the dynamics have changed. While music discovery is a high priority for listeners of new-music based formats, radio no longer has the market cornered. Instead, consumers have the ability to find leading-edged sites and sources that provide them with knowledge and resources. And those who love bands – or brands – can easily navigate to their websites in order to learn what’s around the corner, or even rumored to be. In the past, music directors (when that position existed as a mandatory part of a radio station staff) tended to be involved with record label relationships, music scheduling, and programming of feature shows and specials.

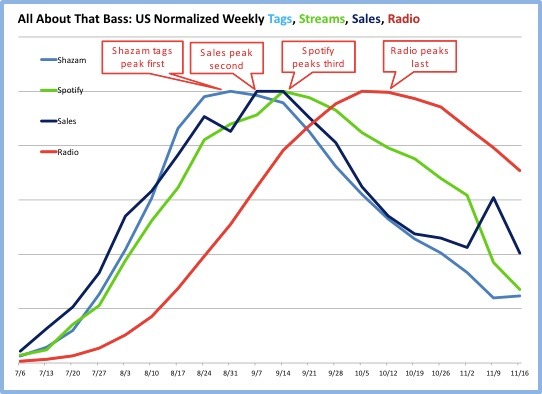

Today, they need to be attuned to how songs and artists are faring on multiple sites, along with keeping up with news alerts and developments on artist websites. It has become a more complicated and demanding job. So when a Spotify Artist blog post by Will Page (their Director of Economics) and Kenny Ning (Spotify Analyst) flew into my inbox the other day, it only reinforced my concerns that broadcast radio is moving further behind the musical curve. The post talks about the power of streaming exposure (on Spotify) for Meghan Trainor’s single, “All About That Bass.” But a deeper look at their analysis reveals a fascinating dynamic between streaming, Shazam searches, and sales. And then there’s radio. Here’s the trajectory of these four variables on Trainor’s song first in the United States:  The first thing you notice is the close connection between Spotify on-demand streaming (green), Shazam tags (light blue), and sales (dark blue). As the chart notes indicate, their peaks are different – starting with Shazam, then sales, and finally Spotify streams. But the three curves are very much aligned, as they rise and fall on essentially parallel paths. And then comes radio (red). You’ll notice that across the country, the song’s airplay tended to lag weeks behind the rapid rise of this song on these three charts – including sales. That last one is the head-scratcher. You can understand how PDs might not be aware of streams or even Shazam tags. But sales should be a rather obvious indicator that something was going on in a big way with this song.

The first thing you notice is the close connection between Spotify on-demand streaming (green), Shazam tags (light blue), and sales (dark blue). As the chart notes indicate, their peaks are different – starting with Shazam, then sales, and finally Spotify streams. But the three curves are very much aligned, as they rise and fall on essentially parallel paths. And then comes radio (red). You’ll notice that across the country, the song’s airplay tended to lag weeks behind the rapid rise of this song on these three charts – including sales. That last one is the head-scratcher. You can understand how PDs might not be aware of streams or even Shazam tags. But sales should be a rather obvious indicator that something was going on in a big way with this song.

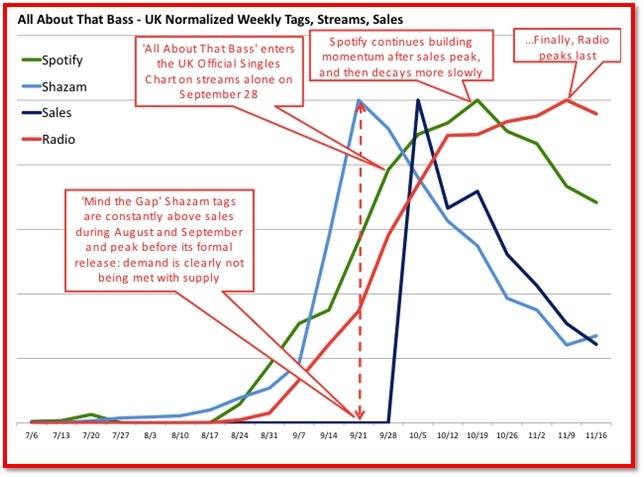

Yet, radio’s curve is late. And then interestingly, long after the song started to head south on the three charts, radio airplay continued to rise, and then tailed off at a much slower rate. Why is this? Is it that many radio stations don’t take this kind of information into account or don’t have access to it? Or does it have more to do with a conservative policy toward new music? Now we’re looking at a lot of radio stations here, probably most of which are in the CHR or Hot AC formats. So does it make sense that they appear to be behind the curve – at least for this song? For contrast, Page and Ning also studied the UK during the same time. The color coding is the same.  There are all sorts of interesting differences here, driven in part by the fact the song was available on Spotify six weeks before it went on sale as a download. Thus, the gap between supply (sales) and demand (Shazam tags), which Page points out. But the other difference is that UK radio is very much in the mix. Clearly, fewer radio stations mean that a big “add” from the BBC can propel a song, as you can see during the week of 9/28.

There are all sorts of interesting differences here, driven in part by the fact the song was available on Spotify six weeks before it went on sale as a download. Thus, the gap between supply (sales) and demand (Shazam tags), which Page points out. But the other difference is that UK radio is very much in the mix. Clearly, fewer radio stations mean that a big “add” from the BBC can propel a song, as you can see during the week of 9/28.

That said, it is clear from these two charts that while UK radio (like in the US) peaked last of the four variables, it was also very much in the mix when the song started to show momentum everywhere else. And in case you’re wondering, Trainor is not a Brit. She was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts. So a few thoughts and possible implications to all of this:

1.Can radio still be the music discovery vehicle for most people? Does it want to be? As Clayton Christiansen might ask, “What job do consumers hire FM music radio to do? Is music exposure still a top job duty for broadcast radio? This data indicates the early adopters on pure-plays might find a song first, and then the Shazam tags begin. For those who are not especially involved with discovering music via streaming services or on YouTube, radio may still be breaking music. In this scenario, however, is radio’s marketing nomenclature off-base? That is, when stations trumpet that “they play the new music first” or even “Here’s the new Lorde,” are they in essence dating and even embarrassing themselves because so many consumers found the song earlier and elsewhere?

2. Shazam is a strong indicator of curiosity and continues to be a useful indicator of a song’s potency. With Shazam, tag levels often jump once airplay begins – an indicator that a song may indeed be a hit because its sparks the need for more information about a song and a band. Programmers have always desired a way to visualize audience interest, and Shazam’s tracking data indicates that it has definitely arrived.

3. Streaming data has value (especially on-demand streaming). With algorithms, exposure happens but not with any consumer impetus. With on-demand streaming channels, however, programmers can get a much better early warning indicator that a song has appeal.

4. Radio (in the US at least) appears to be fashionably late to the party. But it stays longer after everyone else has moved on to the next big thing – even after sales are tailing off. That old adage comes to mind: “When people say they’re tired of a song, that’s the moment to move it up to power.” Or words to that effect. That philosophy has served radio well for decades, but in the face of pure-plays, does radio hanging onto ultra-“burned” songs widen the gap between FM stations and pure-plays? And does radio come off as dated?

5. Is PPM fear creating a culture of music conservatism? Are we seeing statistical indicators that radio is often sandbagging when it comes to new music airplay, hanging back to see what everyone else is doing before taking the plunge? And if some of these or all of these are true, are they necessarily bad things or are they yet another indication that the equation and the dynamic of new music exposure is fluid? Is broadcast radio’s place in the hierarchy of music discovery moving downward? And if so, what are the implications for programming, marketers, and even the musicians themselves?

This doesn’t suggest, by the way, that radio’s influence on an artist, a song, or on music sales is diminished. This exercise is more a matter of timing and brand perception, two variables that are changing because of the influence of digital media. Tomorrow, we’ll explore what this means to radio, and how the fire hose flow of new media and technology begs for a change in the thought process and philosophy of music programming. Does broadcast radio need to reconsider its raison d’être in the digital world?

- Media In 2025: Believe It Or Not! - January 15, 2025

- Every Company Is A Tech Company - January 14, 2025

- The Changing Face Of Social Media (OR WTZ?!) - January 13, 2025

I read this with our non-comm triple A and classical lens on. Our two stations play a lot of relatively unknown music, both new and old. It’s a big challenge for us. For us, it’s all about creating a vibe, a culture where listeners value our curation. But we still see and hear anecdotally that listeners may be utilizing Spotify or Pandora as a choice to fulfill dome need we don’t.

There’s no question that streaming patterns can provide an additional info about a song’s trajectory and interest level. Consumers who “Shazam” songs and/or include them in playlists on Spotify are expressing interest in them in ways that well precede sales…and often, radio play. There’s a lot to be learned. Thanks for commenting, Chris.

I agree with the last guy … I think it’s time for radio to understand its place in the listeners life … Not so much for breaking bands But more so for the companionship and creating the environment that the music exists in . Maybe shifting the focus to finding and developing good jocks like was done the past would help …..there are just too many music outlets out there right now

Happy new year Fred !

Frank

Frank, thanks for the comment. We’re on the same page when it comes to companionship and the importance of DJs. Townsquare is proving they can make small market radio work by focusing on revenue streams that many broadcasters ignore or have simply not considered. Given the heavy competition, as you mention, innovative revenue models are critical to sustainable success. Happy new year to you as well and thanks for reading our blog.