There are a lot of attributes that define great radio programmers. The ability to manage and coach talent, be a visionary, understand marketing and branding, stay organized, and work with the sales department are all skills that most P.D.s must have in order to survive, much less thrive.

One quality, however, has fallen by the wayside: a pair of great ears.

That’s the subjective part and an incredibly nebulous skill. Like great movie directors or even painters, having a keen eye – or ear – is something that often sets the great programmers apart from the also-rans.

But these days, most radio execs would probably put that ability to “hear” the next big hit well down the pecking order of skills. Sure, it’s nice, but nowhere near as important as it used to be.

In fact, so many stations are playing “gold” – catalogue music, as the industry refers to it – that having a sense for older music that resonates with a target audience may be a more important skill.

For many years, the typical way of determining the era parameters for a gold-based station – or one that relies on a substantial library of old hits – was to use a little middle school math.

By determining the time period when a target listener was in her musically formative years – roughly 12-20 years of age – it was relatively simple to carve out a person’s a musical “sweet spot.”

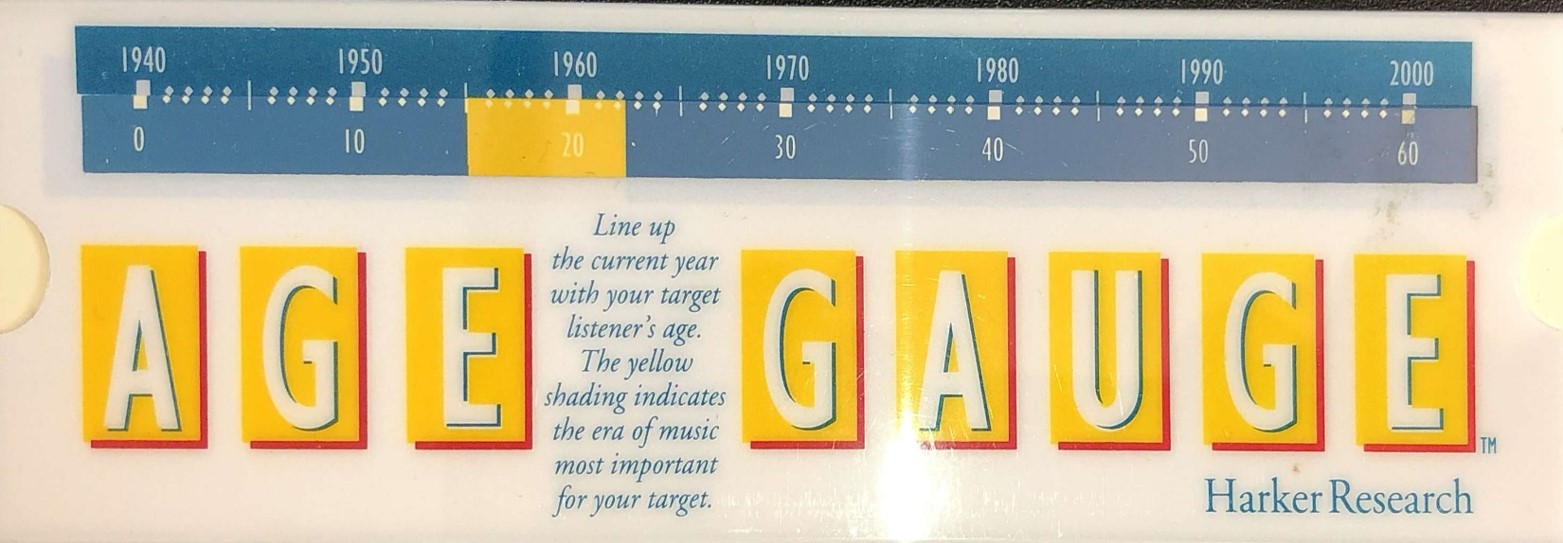

In fact, slide rule type devices, like the one pictured at right were used to help make these calls. There was a reliability to this process because  everyone loves the music they grew up with – right?

everyone loves the music they grew up with – right?

And conversely, if music came out when a consumer was too young to grasp it or too old to “get it,” that would put them outside of the target demo. The theory being that whether it’s Classic Rock, Disco, Hip Hop, Reggae, or Grunge, chances are you won’t listen to it if you didn’t grow up with it.

But if you did grow up with a particular type of music, that’s an indication you’ll like similarly flavored music from that same era. And so will throngs of other consumers who came of age when you did. At least, that the basic idea.

In the technology world, they go about these things a little differently. And in fact they’re pouring considerable resources – human and financial – into reverse engineering the concept of music nostalgia. That is, how can a consumer’s music listening patterns lead to the development of software predictive of other music they want to hear? And how can that process be scaled across larger groups.

Algorithms are the means to that end.

Algorithms are the means to that end.

Late last month, it became clear that Spotify was up to something. The U.S. Trademark and Patent Office revealed that back in June, Spotify received a patent that might turn out to be not just important, but historic.

Ashley King writes in Digital Music News the patent “identifies a user’s demographic group and recommends songs that would be ‘nostalgic’ to that listener, based on previous listening history.”

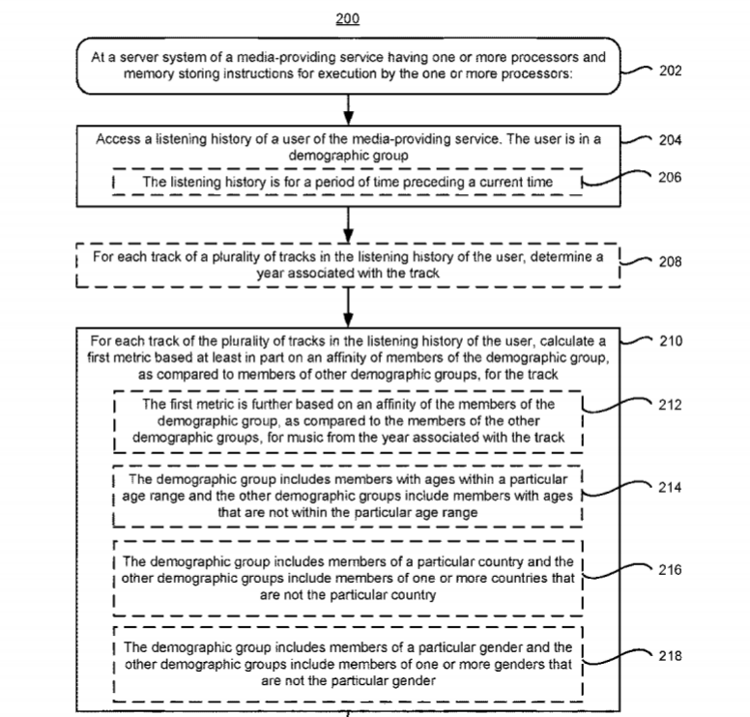

According to the patent, here’s how it works:

“A server system accesses a profile of a user of the media-providing service. The profile indicates a demographic group of the user. For each track or a plurality of tracks, the server system determines a year associated with the track.”

The assumption goes like this. If a Spotify user is a huge fan of Van Halen (the David Lee Roth year: mid-70’s to the mid-80s), the algorithm pulls up other popular songs from users in her same demographic. You can follow the pathway of the process by taking a walk through the logic “sausage factory” Spotify has created. (Yes, I’m a nerd for this stuff because it is fascinating.)

So, there are lots of variables in play in this complex code, including the user’s country and their gender. But like that old radio slide rule, the years of song releases and the ages of listeners appear to be the dominant filtering and correlative elements that lead to the science of extrapolating musical taste.

And perhaps that’s where this algorithmic theory may go astray. I’ve analyzed too much research in the past few decades — perceptual studies, music tests, and focus groups — where I’ve seen people who weren’t even born when certain brands and songs rose to popularity. And in spite of that, these “out of demo” people love this stuff — sometimes even more than the folks who grew up with the music and who fall into the “appropriate” age group.

I’ve witnessed this phenomenon since the beginnings of the Classic Rock radio format’s beginning in the early 80s. Based on their chronological age, people under the age of 45 or so would seemingly have no business listening to music from Zeppelin, Hendrix, and the Stones. But in fact, millions do.

They also go to Classic Rock concerts, buy and wear Classic Rock merch, and know as much about its history as their parents do. In fact, Millennials  and Gen Z’s are often especially enamored with this music — and its seminal era. How else to explain all those and AC/DC and Beatles t-shirts? And that’s the point.

and Gen Z’s are often especially enamored with this music — and its seminal era. How else to explain all those and AC/DC and Beatles t-shirts? And that’s the point.

Spotify may find there is no rational, data-driven, empirical formula that explains the intricacies of music popularity and listener passion. It’s a music Rubik’s Cube that would have stymied Mr. Spock because it truly is illogical.

That’s part of what makes radio programming so challenging, so inspiring, so unpredictable, and so much fun. Much as we may try to put music into nice, neat boxes, much as we may devise our music architectures, much as we may try to automate the process and program the same music for a dozen different markets, real people will continue to throw us musical curve balls.

Is it truly possible to define nostalgia — that amorphous, inexplicable feeling that is linked to a piece of music — a time, a place, a person, an aroma? Can it truly be quantified, scaled, and reproduced across populations?

A statistical formula that analyzes one’s tastes, and then aspires to replicate them across broad demographic groups is designed to fail. Or produce a predictably, bland playlist. of overplayed songs.

Spotify, take that patent and prove your thesis.

But don’t be surprised if it leads to musical chaos theory.

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

Fascinating, indeed. But, much still to be said for results from actual feeling, experience, connection, comfort and curation by the real thing:

Broadcasters.

Clark, we can only hope.

Well stated. For me “curation” is the operative word.

Indeed it is.

Truth, Matt.

I’m with you, Fred. An algorithm can no more program a radio station playlist than it can create good fine art–it is, by definition, artificial, and that’s how it sounds. (Lots of evidence of this on the airwaves already, wouldn’t you agree?) Maybe it’s all right for people who use music simply as wallpaper, but listeners who actually care won’t like it.

And there will always be those like me who, despite being a “boomer,” much prefer shows featuring things not heard before. For me, that’s mostly world music. What’s yours?

John, agree, agree. And it’s your last point that really resonates. We are all anomalies. (I am reminded of this every time Netflix tries to recommend my next show.)

Once Google can perform a constructive and truly teachable air-check session, then we’re all screwed.

Good point. Hopefully, we will pass on these skills to the next generation of PDs, John.

What a fun, interesting read–and brings back great memories of both when I was doing the only contemporary Christian music show in San Diego (long before anyone dreamed of a K-Love) and when I deejayed Christian music skate nights at a local roller rink so packed they would regularly, literally run out of skates. I learned very early on that the people lined up at the booth to make requests were NOT representative of the 95 percent of the people who liked what I played and kept skating away.

In the end, maybe it’s an impossible task because everyone’s favorite song is “The Illogical Song.”

True that, Dave. We learned in the iPod era about everyone’s “guilty pleasures.” How else to explain that Tiffany or Captain & Tenille song on a die-hard Classic Rocker’s playlist. Thanks for the comment.

Is THAT why I have that Partridge Family album next to Led Zeppelin II?? (True story.)

You always were an “algorithm buster.”

LOL!

Great blog, Fred!

Being current with a classic rock radio show and listener comments on my social media pages, the ones who weren’t there for the first go round find musical surprises stimulating. A recent comment was on a discovery of a greater level of appreciation for PAT BENATAR through one of the “deep tracks” on my weekly Classic Rock radio program. The Spotify attempt to quantify her taste would fail to make the connection.

With an on-air tag of Lobster, the word comes up a lot in my posts. Therefore, the algorithms employed started showing me ads for companies that ship Live Lobsters. I wonder…Are we reduced effectively into data assumptions based on responses to music that have intangible roots in emotions and memories?

Perhaps, yes. And as we’ve learning, not all those data assumptions are close to accurate, even if they seem logical. The Pat Benatar story is a good one. She’s not the Who or even Aerosmith. But for a true fan – of any age – appreciation of an artist transcends bits and bytes. Thanks, Paul, for always adding to the conversation.