I always know something’s going on when more than a few people send me a news story “that make a great blog post.” That was the case last week when Steve Goldstein, Jim Cutler, Brother Bill, and a couple others sent me a devastating essay in The Atlantic by Ted Gioia, author and observer of all things music. The title of his opinion piece ought to be enough to send shivers down your back, whether you’re in the music, radio, or streaming business:

“Is Old Music Killing New Music?”

The headline had a ring of familiarity. A quick search of JacoBLOG revealed I wrote a blog with a similar title and an eerily similar ring last January. In fact, I reran it as a “Best of” late last month. My pithy title was “Can New Music Compete Against Classic Rock?” and it explored many of the same themes Gioia lists in his lawyer-like takedown of the new music environment, especially the record labels.

He and I both agree the swing toward “old music” (can we just call it “classic?”) hit hyper-speed during COVID as legions of freaked out people retreated to the familiar, cushy confines of nostalgia. But this trend was in play long before we started wearing masks and arguing about the vaccine. Back in 2019 in the UK, three of the country’s top 10 best-selling albums were greatest hits compilations by Queen, Elton John, and Fleetwood Mac – not exactly the latest and greatest music.

It is fascinating to watch our current phase, given my experience with Classic Rock in the early 80’s where the question always was, “But will it last?” Now, respected music critics and pop culture observers are asking the same question about new music and new artists.

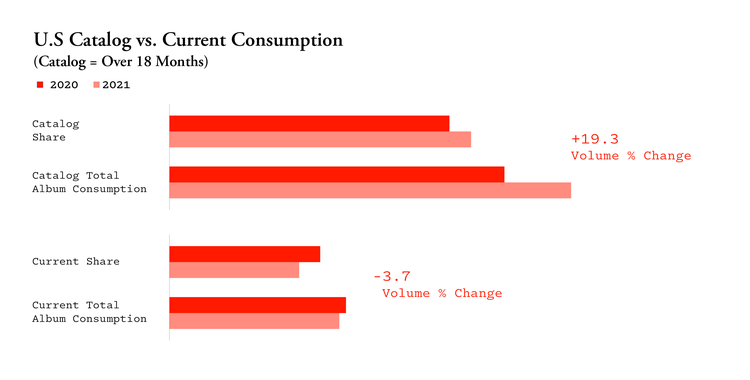

In his analysis, Gioia goes right to the data to support his contention that even among “streamies,” the musical diet is laced with gold. The subhead of his opinion piece is like a “spoiler alert” – a tipoff about what’s to come:

“Old songs now represent 70% of the U.S. music market. Even worse: The new-music market is actually shrinking.”

And Gioia uses data to back up his claims, citing MRC research from the past couple years:

And these numbers aren’t just based on Baby Boomers listening to their old King Crimson and Steely Dan records. A devastating stat in The Atlantic piece underscores the fact that even streaming has turned old.

Very old.

Gioia notes “the 200 most popular new tracks now regularly account for less than 5 percent of total streams.” Three years ago, that number was twice as high. In aggregate, there’s more streaming going of Grand Funk-era songs than Arianna Grande music.

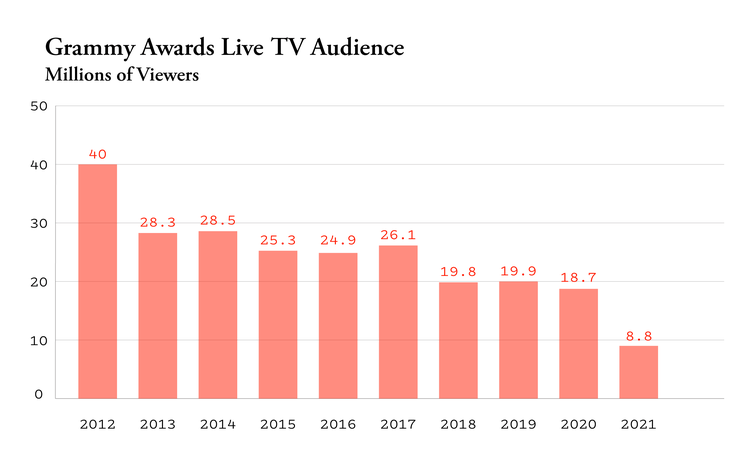

For breakout new songs, it’s a puny performance, and it’s headed in the wrong direction. To prove his point the issue goes beyond the music and permeates the culture, Gioia cites the crash of Grammy Award ratings as proof positive most consumers just don’t give a rat’s patootiee about new music. Now in general, awards shows have almost all been down-trending, hitting new lows during these past two COVID seasons. Still, these numbers were sinking pre-pandemic, hitting an all-time low last year.

Gioia makes the assertion that never before in history has new music had such a miniscule impact on our cultural fabric.

In the meantime, Classic Rock is bringing home the bacon…and the eggs, the hash browns, and the entire menu. The gold rush to buy artist catalogs is full steam ahead, including Mt. Rushmore icons such as Springsteen, Dylan, Bowie, and Steve Nicks. Expect more of these “sales” in the coming months and years as classic artists cash in on their catalogues.

It is also noteworthy the best-selling physical music format today is ironically vinyl. Now keep in mind that most people aren’t actually purchasing music anymore – CDs, cassettes, mp3s, or records. But of those who just have to own it , vinyl is back in style, underscoring the trend that what’s old is cool.

records. But of those who just have to own it , vinyl is back in style, underscoring the trend that what’s old is cool.

And Goia concludes by claiming the future for new music is not a bright one. that’s because record execs have lost faith in discovering new artists, styles, and genres. He points to label investment gathering momentum in the catalogue silo, while it continues to head backwards in the new music category.

I get nervous when analysts in any field – movies, finance, health and fitness, and yes, music – start making sweeping conclusions based mostly on the last two years. The debate over the workplace falls into this zone. We simply are not going to know where we’ll be doing our jobs a year or two from now. We can’t predict how our lives will evolve on the other side of the pandemic.

Assumptions about where music is or isn’t going are difficult and dangerous when based on 2020-21 trends for all these reasons. COVID has broken our compasses, making forecasting precarious at best.

The pandemic is an anomaly. But much of the data surrounding new music’s trajectory were already trending down before we were arguing about masks. I liken it to online shopping – in reverse. During the last five years, more and more of us were doing our shopping online, thanks in no small part to the explosion of Amazon Prime. COVID accelerated that trend, forcing brick-and-mortar stores like Macy’s, Walmart, Nordstrom, and even local retailers to establish and or bulk up their e-commerce efforts.

Interestingly, Gioia finishes his piece with a ray of hope. That’s because he’s certain – and I share this belief – that “the next big thing won’t sound like the last big thing.” That’s my quote, and I believe it stands the test of music discovery time. When we expect the next wave of music to sound like the current fare, it’s easy to miss what’s next.

Elvis didn’t sound like Sinatra. The Beatles didn’t sound like Elvis. The Sugarhill Gang didn’t sound like the Beatles. And Nirvana didn’t sound like the Sugarhill Gang.

Simplistic? Perhaps, but most corporate music mavens never saw these changes coming. We laugh now at the record executives who missed the next hot trend or failed to sign a great band. But that’s the whole point of not knowing where we’re going…until we already get there.

Gioia’s conclusion about how this story might end:

“…not with the marginalization of new music, but with something radical emerging from an unexpected place.”

When does this happen? In this environment, how can it happen? Will it even happen? Good questions all. None of us knows how this saga will play out. Is the end or is it just the beginning?

Still, you have to wonder whether the conditions that enabled new music discovery – and let’s give radio its due credit here – have![]() changed, perhaps permanently making it difficult to expose new music on a mass basis.

changed, perhaps permanently making it difficult to expose new music on a mass basis.

That’s one way of looking at it. But I have a sense of confidence the new music conundrum will, in fact, sort itself out. There will be great new bands, artists, songs, and genres that will surprise, delight, and remind us we’re on a cultural roller coaster that while far from flat, has its shares of thrills…and maybe even spills.

And you’re hearing this from the Classic Rock guy.

Tomorrow, a second part of this blog post will venture out and predict how this might happen, and whose voices will be heard.

You can read Ted Gioia’s piece in The Atlantic here.

- In Radio, You Just Never Know - April 17, 2025

- The Secret To Making A Great Podcast (And Great Radio) - April 16, 2025

- I Read The (Local) News Today, Oh Boy! - April 15, 2025

I read the article the other day and I’m not sure his math isn’t skewed.

The 200 most popular songs represent only 5% streams and that number is half what it was three years ago.

You have noted in the Tech Survey the increasing use of streaming services by older adults.

People who probably are not in a new music discovery phase in their lives.

A streaming account can make it easy to spend a Saturday in the garage with Springsteen or a Saturday night with Lou Reed.

I think the later adaptation of the services by older adults may account for some if not all of the skew.

A lot of 50+ people “learned” the art of streaming during COVID – and they’re not going back. Do they outweigh the impact of Gen Z and Millennials? No, but there are enough of them to skew the totals as you point out. Meantime, new Techsurvey results coming out.

New title sales went in the toilet back in the ’90s and never came back as far as I heard! Every innovation I can think of came from independent labels and not the majors. Their owners cashed out and no new generation replaced them. The infrastructure of local venues where young musicians got paid is long gone and playing music became a hobby as opposed to the path out of poverty it had been in the ’50s and ’60s. The majors have always taken today’s throw it up against the wall and see what sticks approach.

There are some huge opportunities that this has created but I’d look to people in their early 20s to figure out that it requires live performances to test musical innovation.

So many of the “givens” have changed, Bob, thanks to the combination of digital and CONVID. The “rules” of how an artist can be best marketed are in shreds. It is going to take some serious innovation and risk-taking for aa new model to emerge. Check out tomorrow’s post and let me know if you think there’s a “there there.”

This paragraph in his article is a large supposition that drives his whole argument…

“Only songs released in the past 18 months get classified as “new” in the MRC database, so people could conceivably be listening to a lot of two-year-old songs, rather than 60-year-old ones. But I doubt these old playlists consist of songs from the year before last. Even if they did, that fact would still represent a repudiation of the pop-culture industry, which is almost entirely focused on what’s happening right now.”

Calling an 18 month old song “old” beefs up the “alarm” of this argument greatly. That’s a “recurrent” in most programmers minds that would still represent current trends and artists on the music scene.

I don’t doubt the strength of catalogue artists obviously. I’m still devoting much of my radio work into tapping into it. But I’d find Ted’s article more convincing if the “old” music category was based more on 18 years old as opposed to 18 months old.

I agree with your point, I think, Fred…that Ted buried his lead.

The more pertinent excerpts from this essay are these. “The problem isn’t a lack of good new music. It’s an institutional failure to discover and nurture it….New music always arises in the least expected place, and when the power brokers aren’t even paying attention. It will happen again. It certainly needs to. The decision makers controlling our music institutions have lost the thread. We’re lucky that the music is too powerful for them to kill.”

Also,, is something not ‘new” music if it echoes classic styles? There’s a ton of great new music in the traditions of Boomer’s favorites, particularly in the Americana division, but there are next to no radio outlets out there to elevate it… so record companies don’t invest much in getting them more popular. Brandi Carlile is a good example. A fabulous talent in virtual obscurity for 15 years until she broke through…but in spite of mass appeal radio and her own record company paying scant attention to her remarkable talent. I could name 20 other artists as strong as her wallowing under the radar that Boomers, X’ers, and Millennials would all dig if they were heard anywhere else besides obscure Satellite channels like The Loft or on AAA public radio stations [or on my show 10000 Good Songs!] https://exchange.prx.org/series/37247-10-000-good-songs

Jason Isbell, Sarah Jarosz , Aaron Lee Tasjan, The War and Treaty, Laura Marling, Kingfish Ingram…you can argue they all makes “new” music that sounds like older music but it’s absolutely new music …not boosted by whatever record / radio hit-making industry that exists today.

My profs in college always said, before starting your thesis, “define your terms”. Ted’s piece is muddied by his lack of attention to that truism of a good essay.

Unless you really dig, pretty much all the ‘new music’ we have today is the end result of the manufactured pop icons from the ‘star maker machinery.’ Sure, it’s kinda’ always been that way, but today’s pop stars and their manufacturers have it down to a science. (look no further than KPop to see how this all turns out in the end) Until someone comes along and throws a monkey wrench into the machinery, and smashes it into a thousand pieces (here’s hoping) , it’s what we got.

There could be a silver lining for radio here, Fred. Walk with me on this.

When I began my path as a music seducee in the 1950s, and a collector in the ’60s, it was well before the massive proliferation of music we’ve experienced in more recent years. That is, staying atop much of it wasn’t yet a superhuman task. Radio stations really helped with discovery, but acquiring the physical medium (vinyl at that time) and listening to it offline were ubiquitous activities for most of my generation.

Sometime around the 1980s, I’d estimate, it seemed no longer possible to drink the stream; it was becoming a Niagara Falls. Like you, a lover of music as well as radio, I couldn’t keep up with it all. New forms of music arrived often enough to rekindle my love for it at intervals, but there were/are so many artists, so many genres, so much of it great–breathe deeply. Meanwhile, all that “catalog” music never faded.

What’s the melomaniac to do? Without any conscious plan, I found myself relying more and more on the radio, while my thousands of LPs and CDs gathered dust. I’m listening to a local AAA station on the “regular radio” in my study as I write this. They play classics, new stuff, and the in-between throughout the day, and they do it well enough that I don’t tune away during the commercials. Without radio, I’d be lost and my days would lack the oxygen I need. I can’t be the only one.

Long live radio.

“Sometime around the 1980s, I’d estimate, it seemed no longer possible to drink the stream; it was becoming a Niagara Falls.” Exactly. When those “classic” artists were coming up, there were just a handful of stations in each city (and many of those with overlapping or even duplicating formats) playing their music. It was relatively easy to keep up with all the new music–not because they played every garage band kids were forming–but because they were the only access TO new music. Now, even if you wanted to keep up with all the new music, it’s no longer possible.

I’m spoiled. I was there for The Beatles. I was there for Billy Joel. I was there for Queen, Elton John, Mariah Carey, Whitney and Michael and the 90’s. I’m here for N’Sync and BTS – and none of this points out to the distractions that people are having from other entertainment sources. Gaming, videos (Youtube) and other ways to be distracted. It’s also missing the point that back in “the day” broadcast radio was a source for most “new music”. Today there are myriad streaming sources, and not every “new artist” is on every streaming source. The haystack is growing and the needles (new songs/artists/albums) are getting more and more hidden. Will this solve itself? Maybe not. When Frank, Elvis and The Beatles was the “next big thing”, the discovery resources were limited. Not today. My “next big thing” may not be yours. Electronic media has experienced “fragmentation” for decades. Can you see a way that this will lessen, ever?

Maybe not, Dave. But I (stubbornly) believe that while the platforms have grown exponentially, it is still hard to find “great radio” whatever you listen to. (See the Bob Waugh comment.) Thanks for commenting.

Fred,

Looking forward to tomorrow’s piece.

from MRC (BDS) streaming and airplay data, last week.

Top 100 streams in US avg year is 2020.3

Top 100 radio airplay in US avg year is 2020.6

Top 100 streams in Canada avg year is 2019.7

Top 100 radio airplay in Canada avg 2016.2

New music is there and being consumed. No more than 12 titles on any of these lists are pre 2013.

Drilling down into genres/formats/geo could tell some other stories.

Appreciate this, Doug. LMK your thoughts on today’s Pt.2.

Hi Fred.

There are many factors that have played a prominent role in the decline of the Grammys viewership. I’m not sure I’m buying in to the extrapolation that the general public’s interest in new music deserves this epitaph.

Boomer music aficionados such as myself still exist at many of the most credible AAA stations in the country. We have equal interest in exposing Elvis Costello’s new album as we do a new act like Wet Leg or the latest from our format dominant Lumineers. As Gene Sandbloom recently pointed out, the survivors among us seem to be re-defining the concept of “New Music Discovery” to include younger demos that have never before been exposed to some of the “Golds” from the Classic Rock, 80’s, Grunge eras. Hopefully, there’s enough of an audience (for AAA, at least) that still appreciates antiquated musicologists, such as myself : ) who are the gatekeepers that choose to champion new, exciting and emerging artists like Maggie Rogers, who will be headlining MSG later this year.

Bob, great to hear from you on this gnarly, but fascinating topic. I’m glad you’re continuing to do what you do on the airwaves. That institutional knowledge – and instinct – you bring can’t be programmed into an algorithm. At least not yet.

I think the numbers are skewed as well. Grammy viewership is like every awards show…going down. Even the Olympics and World Series have declining viewership. It’s generational…..like radio itself. And, 18 months is how long a tune is ‘new’? Too many other statement I disagree with in the article. News/Talk remains the #1 format and the ‘old artists’ may be cashing out….but they are still making new music.

Enjoyed this read. From what I hear the audience isn’t watching because its ecome too political, celebrities are over exposed. When fans were watching those shows it was when celebrities weren’t in your face 24/7.

Jeff, thanks for the comment. It IS complicated, as I’m sure Ted Gioia would admit. Like a lot of data, you have to read and consider this stuff carefully. But there’s a trend here, don’t you think?

Trying to figure out who or what will be the next “big thing” always reminds me of the infamous? line from the Decca executive who said of the Beatles in 1962: “We don’t like their sound. Guitars are on the way out.” You may as well try to predict the next earthquake. All you can do is wait, and when it happens, you’ll know.

As the famous line goes, “Nobody knows anything.” At moments like the one your describe (and probably the one we’re in now), this is so true. Thanks, Dave.

I wonder if the music of the 20th century will simply become like that of previous centuries. Most Classical music (i.e. orchestral) listened to now is deeply routed in the past, written in an earlier century, maybe played now by a very much alive orchestra. Substitute a playing orchestra for a rock “tribute band” or a play on Spotify/Youtube or an oldies radio station, in the case of rock – and you’ve pretty much got that same model. Pareto applied, and only 20% of what you might hear in future is new, only 20% of people will even want to hear it.

Chuck into the equation an ageing population in the countries where it was most made, you have the “rock generation” not wanting to get old, by revelling in the nostalgia of easily-accessible music from when they were 15 years young.

There will, inevitably, be an increase in rock star deaths, those who are revered as the greats of the genre. And I wonder who will emerge to replace them, will there ever be another incredible music era for our grand children?