Next month, those of you who believe in the stock market as an investment option will have an interesting decision to make. That’s when the Spotify IPO become available.

For millions of consumers, Spotify has become a go-to music platform. And we see our kids gravitating to Spotify (and away from Pandora) as their preferred streaming music source.

So, what’s wrong with making a little investment in Daniel Ek’s company in the hope of turning a tidy profit?

Well, if you talk to tech analysts about Spotify’s business model, you’ll learn there are endemic problems. First and foremost, Spotify doesn’t scale.

You hear the S-word all the time in discussions of biz plans and start-ups. But what does “achieving scale” actually mean – and why is broadcast radio actually a better bet than Spotify when it comes to “scalability” – even given its “old media” status?

Business consultant Josh Lowry describes it this way:

“Scale is another word for size. Companies can leverage their size by negotiating exclusive dealings, favorable terms and volume discounts with other organizations. Partnering with large businesses can also provide companies with access to national and world-wide markets to sell products and services. In addition, keeping costs low or unchanged while increasing sales volume provides companies with the opportunity to further decrease prices – new customers, more market share – without sacrificing margin (economies of scale).”

And size matters. You can now say Entercom has achieved scale with its purchase of CBS Radio. It now has strong holdings in some of the most important markets in radio – especially the biggest ones. That footprint allows them to scale areas like sports radio and even the alternative format, given its widespread holdings.

Other radio examples abound. EMF is well on the road with its K-LOVE and Air 1 networks as is Salem in the Christian radio sector. Syndicators like Premiere and Westwood One are all about scale, as are widely distributed personalities from Dave Ramsey to Bobby Bones to Rush Limbaugh. NPR programming is all about scale, as its award-winning shows are heard on hundreds of public radio stations around the U.S.

National promotions, collective contests, podcasts, and other media products become scalable with a big enough megaphone that virtually covers the country – or the globe.

That doesn’t mean smaller companies can’t scale up – especially in a niche area. But clearly size is an advantage to companies eager to achieve scale.

That is, until it’s not.

And that’s the core problem facing Spotify. An analysis by Bloomberg Businessweek’s Shira Ovide suggests that despite having 70 million paying subscribers, Spotify’s model is just not scalable.

Yet, the company is projecting nothing but growth. Spotify CEO Ek told Wall Street that number is expected to climb to 96 million paid subscriber by year’s end, generating $6.6 billion in revenue – an increase of 30% year over year.

Ovide notes how often – and incorrectly – Spotify execs compare their business model to Netflix – streaming video vs. streaming audio. But the big difference is that as Netflix grows its subscriber base, its video acquisition costs don’t rise.

Ovide notes how often – and incorrectly – Spotify execs compare their business model to Netflix – streaming video vs. streaming audio. But the big difference is that as Netflix grows its subscriber base, its video acquisition costs don’t rise.

Spotify, on the other hand, is saddled with music royalty issues – just like other streaming services. Ovide says their 35 million songs become more expensive as more users sign up and spend more time with the service.

That’s because the music industry’s royalties system makes it impossible for Spotify to achieve scale. And as counter-intuitive as it sounds, the bigger Spotify becomes, the more its expenses eclipse its revenues.

But let’s step beyond the Spotify vs. Netflix comparison. Instead, consider the scalability of terrestrial radio up against the Spotify model.

Broadcast radio is one of the most scalable media businesses. Once the FCC approves a license, a radio owner needs to invest in a transmitter, a tower, a building, and a staff. And that’s when even a local station in a small market can “scale up.”

A radio station can double its cume with the help of a better format, research, and marketing – while its gross expenses remain essentially fixed. Even in this turbulent media environment, radio’s business model is enviable.

While many in the tech world are critical of the “old school” radio paradigm, the fact is that broadcast technology is actually brilliant. It’s free, there’s no buffering, it’s seamless, its ubiquitous – and most people are still listening. When we’re talking scale, few businesses can top radio’s efficiency.

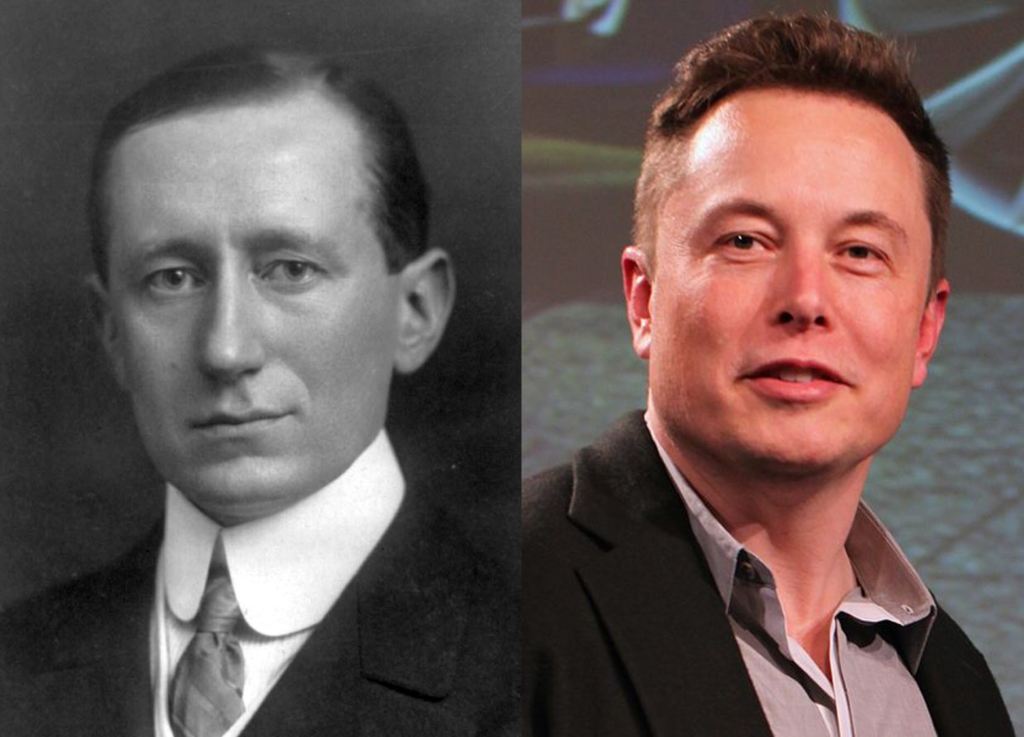

If Marconi would have invented radio a decade ago, he’d have been hailed as the next Elon Musk. (He’d might even have his own reality TV show, “Meeting Up With The Marconis.”)

But aside from its amazing technology, it’s the scalability piece where radio truly shines – especially in a world of streaming models that don’t work unless you’re Apple, Google, or Amazon – and you have other little businesses profitable enough to overcome the onerous model that is music streaming.

So, next week, do you call your broker or log onto your stock trading account and take a flyer on the Spotify IPO?

Or perhaps consider investing that money in a broadcast radio stock of your choice.

I’m no Jim Cramer, but that’s what they call smart money.

- What To Do If Your Radio Station Goes Through A Midlife Crisis - April 25, 2025

- A 2020 Lesson?It Could All Be Gone In A Flash - April 24, 2025

- How AI Can Give Radio Personalities More…PERSONALITY - April 23, 2025

Agree on your assessment. The investment play here (if you have the stomach for it) is a put option, or a short sale of stock. A put option is a bet that the stock price will go down after the IPO excitement of going up. That is the short definition. Search Put Options or Stock Short Sales for ALL the details, and there are many. Profits can be fast and high, losses can be expensive.

Joel, it’s a tough play. Not sure I’m willing to bet on the put option either. But certainly on paper – despite all those subscribers and the buzz that will accompany the IPO – it’s a difficult company (for me) to invest in. Thanks for the comment.