The term, “community,” is used in myriad ways by media and brand strategists. If you’ve been following Seth Resler’s “Connect the Dots” blog over the last couple of years, you’ve read all about communities – how to nurture and encourage them.

Jimmy Buffet’s death on September 1 sparked a multitude of conversations about fans, fanatics, and communities. This phenomenon isn’t uncommon in music circles. And as more and more fans think nothing of flying to different cities to “go on tour” with a favorite artist, we may be seeing an acceleration of communities – people looking for a group of like-minded individuals with whom they can bond.

Seth’s guest blog post today is thorough and detailed. It may be something you put aside for when you have more time to let it soak in. It IS an important way to think about fandom, audiences, and how they form and grow.

Please leave your feedback below in the “comments” section. – FJ

By Seth Resler

When Jimmy Buffet passed away a few weeks ago, Fred sent me an email. Knowing that the concept of community building is a favorite topic of mine, he suggested that I write about the Parrothead community:

“Second only to perhaps the Grateful Dead community, Buffett’s realm is impressive given the lack of consistent radio play and only two real hits – ‘Margaritaville’ and ‘Cheeseburger in Paradise.’ It very much fits your thesis and could be a great opportunity for you to set up your NAB appearance this fall.”

In October, I will host a session on “Community Building Strategies for Radio” at the NAB Show in New York, and while I never shy away from an opportunity to plug my appearances, I wasn’t fully convinced that Parrotheads — the legion of fans that Jimmy Buffet has built over the last few decades — actually constitute a community. After all, I’ve gone to great lengths to draw a distinction between an audience and a community. Do Parrotheads really fit the definition of a community, or are they merely an audience?

What is “Community”?

This week, PRPD is hosting its 2023 Content Conference in Philadelphia. The opening session at this annual gathering of public radio broadcasters focuses on a recent meta-analysis of over two dozen public radio research studies. The central takeaway?

“While this report elevates a number of discrete themes and takeaways from these studies, something broader and more implicit emerges. Namely, for public radio to both survive and thrive in the near future, there will need to be a shift in mindset from a newsroom-driven or producer-driven approach, to one that focuses on serving the community as a whole.” [emphasis theirs]

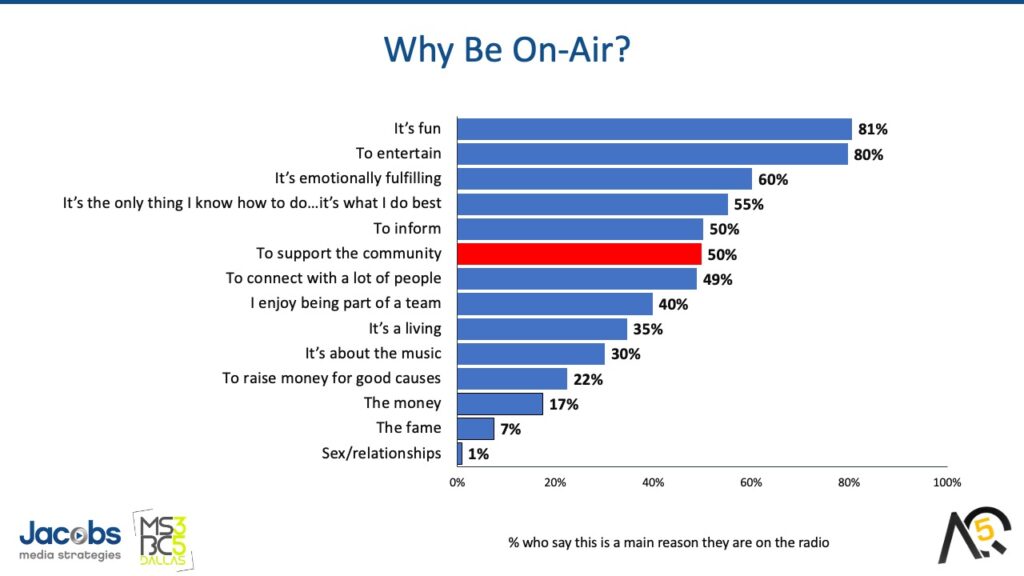

But community is not just a hot topic in public radio. Last week, we presented the results of AQ5, our annual survey of on-air talent. When we asked on-air personalities what they enjoy about their jobs, half of the respondents cited support of the local community:

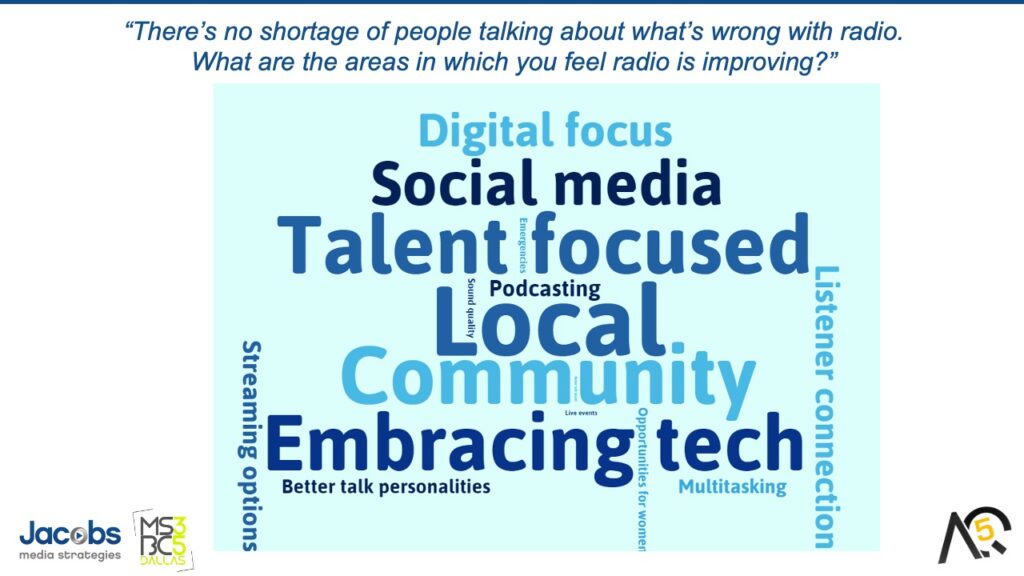

Moreover, when we asked on-air personalities what the radio industry is getting better at, “community” emerged as a source of pride. Here are the answers to this open-ended question in the form of a word cloud:

Clearly, we are already using the word “community” a lot in our industry, and I expect that will only increase in the coming years. Yet too often, the word is misused or poorly defined.

In radio, we like to toss around the phrase “live and local,” and there’s a temptation to use that phrase interchangeably with “community.” But they’re not the same thing. “Live and local” describes content, while “community” describes a space where people connect. Content can be an important component when building a space, but content alone cannot create a space. In other words, with content alone, you can grow an audience, but not a true community.

A Fanbase: A Community That Originates With Content

Yet many creators have found a way to use their content to launch groups that look a lot like communities, not just audiences. So I asked David Spinks, the co-founder of CMX (a community of community managers) and the author of The Business of Belonging, if fans of artists like Jimmy Buffet could in fact constitute a community. He said:

“Swifties, Little Monsters, Juggalos, Deadheads… musicians and bands have long formed cult-like fanbases. Fanbases are a unique kind of social group. They’re like an audience but with much more participation. They’re very centered around the creator which makes them unique from interest based communities or communities of practice that can be more decentralized. Without the creator, the community doesn’t exist.

They have a lot of the markings of communities and even cults: they wear the same “uniform”, they create their own language, they have rituals, and conform to a unique set of values. They create content, trade merchandise, and talk to each other online and offline.

So are they a community? I’d say absolutely. But it really doesn’t matter what I think. What matters is if the members feel a sense of community. I imagine if you ask anyone who identifies as a Parrothead if they think it’s a community, they would most emphatically say ‘yes’.”

I like this concept of a “fanbase” — a group that starts as an audience centered around content, but over time, takes on the characteristics of a community. We see fanbases like these not just in music, but also other forms of content. For example, Trekkers (Star Trek), X-Philes (The X-Files), Losties (Lost), Browncoats (Firefly), and Whovians (Doctor Who) are all fanbases. Each of these groups started as audiences, but over time the audience members found ways to connect with each other by gathering in spaces. Sometimes these spaces are physical (think Star Trek conventions or Comic Con); other times, these spaces are virtual (such as message boards or social media groups). The fanbases are different from other communities, such as Chambers of Commerce, Parent Teacher Associations, Alcoholics Anonymous and others that originate with a shared purpose. In other words, most communities start with a shared purpose and create content to support that purpose; fanbases start with content and, over time, a shared purpose organically emerges among the audience members.

By this definition, sports teams can also be viewed as having fanbases: Initially, audiences members are attracted to the content (the games and matches), but over time, they connect with each other in spaces (stadiums, sports bars, etc.) and evolve into a community.

The Trouble With Fanbases: Not Everybody Is A Community Member

Carrie Melissa Jones is the co-author of Building Brand Communities. In the book, she and Charles Vogl specifically cite Lady Gaga’s Little Monsters as an example of a fan community, so I was interested to get her take on Jimmy Buffet fans. When I asked her if Parrotheads constituted a community, she replied:

“A community is a group of people who share a mutual concern for each other’s well-being. As an outsider, even though I enjoy Buffet’s music and have visited Margaritaville resorts and restaurants, I have never experienced that mutual concern. My interactions with the Buffet brand have always felt transactional, and I have never felt any deeper connection. However, there is undoubtedly an insider core group who share a deep connection and a mutual concern for each other’s well-being. These fans are the true members of the community. The rest of us are just an audience.”

She brings up an interesting point: If a fanbase originates with content, it can contain people who are just audience members as well as people who are active community members. How do you know which are which?

To put it another way: Exactly when does a Swiftie become a Swiftie? When they attend a concert? When they buy a T-shirt? When they call themselves a Swiftie?

Mark Schaefer, the author of Belonging to the Brand, dedicated an entire chapter in his book to the difference between an audiences and communities. He offers some insight on the Jimmy Buffet question:

“There are three properties that are different between a community and an audience.

-

- Do people know each other and work together?

- Is there a unifying purpose beyond consuming content?

- Does that mission change over time as the world changes? In other words, is the community in charge?

Spinks, Jones, and Schaefer seem to agree on this point: A fanbase can be a community, but it ultimately comes down to what the individual fans do and how they feel about their relation to each other.

Signs of a Community

As radio broadcasters, we are content creators. But how do we know if our content is fostering community or simply building an audience? The answer isn’t always clear, as we may have a fanbase that contains both audience members and community members. Here is a list of questions to ask when thinking about your station’s listeners.

1. Do they share mutual concern for one another?

Carrie Melissa Jones and Charles Vogl believe that “mutual concern” is the key factor in defining a community. Frankly, this was thing that gave me pause when considering the Parrotheads. Do they really care for one another? For example, I have seen alumni from the same college, fraternity, or sorority look out for one another even if they don’t know each other personally simply because they consider each other members of the same community. Do Buffet fans behave in a similar manner?

Do your listeners?

2. Do they have a shared purpose?

Jones and Vogl also talk about the importance of community members sharing at least one value and a sense of purpose. This concept is exemplified by Podcast Movement, the podcasting conference that has cultivated a robust community of podcasters who all have a common purpose: they want to become better podcasters.

Do Jimmy Buffet fans have a shared purpose? Yes: They all want to enjoy Jimmy’s music.

Do you radio station’s listeners have a shared purpose?

3. Do they gather in a space for shared experiences?

Content creates audiences; spaces create communities. For content creators like Jimmy Buffet to give rise to a community, there needs to a space — virtual or physical — where the members can connect. For Parrotheads, this is not only the concerts, but also the many restaurants and other establishments that are part of the Buffet empire.

Unlike the music at concerts, TV shows are usually consumed at home. For the fanbases of shows like Lost, internet message boards became spaces for fans to connect and become community members.

Radio is most often consumed in the car. Is your radio station creating other spaces where its fans can connect with each other?

4. Is it part of their social identity?

Both David Spinks and Mark Schaefer discuss the importance of social identity when it comes to community building. As Spinks puts it:

“Humans form much of our personal identities around the shared identities of the groups we participate in. We adopt the beliefs, styles, language, symbols, rituals, and other forms of expression that exist within the groups we’re a part of…. The extent to which a person adopts the shared identity will play a big role in how strongly they feel a sense of community.”

One way to know if a fan views particular content as part of their social identity is to ask whether they use that content to convey something about themselves to other people. For example, when I tell people that I am a big fan of The Wire on HBO, I want to let others know that I am an intelligent, sophisticated, discerning television consumer — or “snob” for short.

When Parrotheads proudly declare their Parrotheadedness to the world, are they trying to convey something about themselves to others? Yes: They are sending a message that they are laid back and ready to live the beach bum lifestyle.

When one of your listeners says that they are a fan of your radio station, are they trying to say something about themselves?

5. Are there boundaries to the membership?

Spinks points out that “All communities are exclusive in some way.” In fact, he argues that dividing lines between who’s in the community and who’s out are important:

“Don’t feel guilty when excluding people, because it’s the exclusion that makes members feel safe, knowing that the people in the room are those they can trust, and whose values they align with.”

With most communities, the boundaries are obvious. You’re either in the NRA, the ACLU, or the Church of Scientology, or you’re not. There’s no ambiguity.

But with fanbases, it’s not always cut and dry. This comes back to the question raised earlier: When does a Swiftie become a Swiftie?

This concept of boundaries gave me pause before labeling the Parrotheads a community. I came of age during the 90s, and we would often joke that a band like Nine Inch Nails was cool until your little brother started wearing their T-shirt. This is another way of saying that when anybody can join a community, membership starts to lose its value. The concept of bands “selling out” because they gain more fans, or of the bragging rights associated with liking a band “before they got big,” is a reaction to the fact that with fanbases, there isn’t a clear dividing line between who’s a member and who is not.

brother started wearing their T-shirt. This is another way of saying that when anybody can join a community, membership starts to lose its value. The concept of bands “selling out” because they gain more fans, or of the bragging rights associated with liking a band “before they got big,” is a reaction to the fact that with fanbases, there isn’t a clear dividing line between who’s a member and who is not.

This highlights the tension between building an audience and building a community. When building an audience, you typically want to attract as many people as possible, so you try to lower the barrier to entry. When building a community, you care more about getting the right people to join, so you purposefully implement gatekeeping. Audiences emphasize quantity, communities emphasize quality. Fanbases do a little of both.

How Can Radio Stations Transform Audiences Into Communities?

Like Jimmy Buffet, radio stations are content creators. While some content creators are able to foster communities by creating interpersonal connections that go beyond audiences, not all content creators are able to do this. What can your radio station do to increase the chances that your audience evolves into a community?

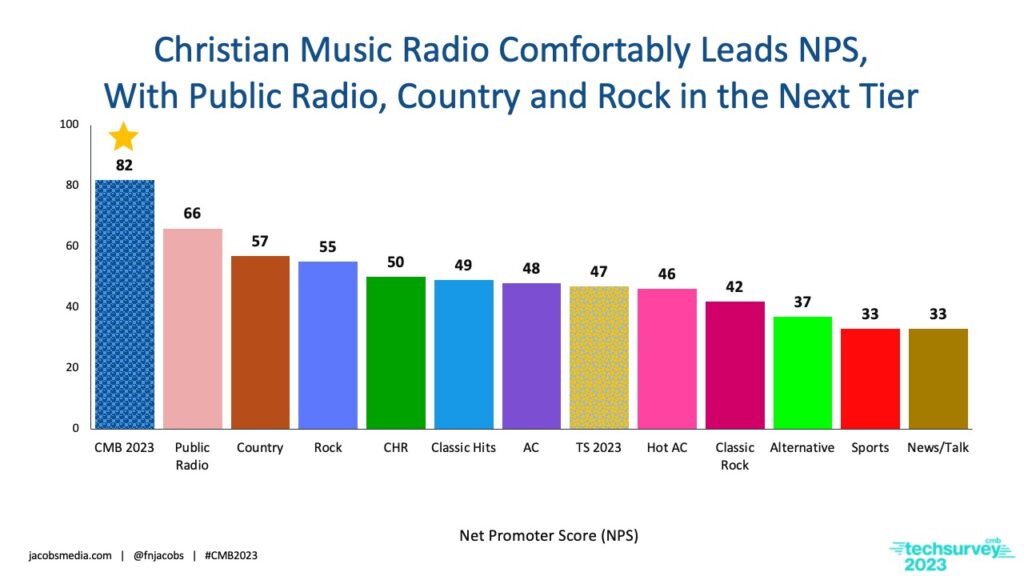

1. Encourage concern for fellow listeners. Know which stations are really good at this? Christian radio stations. Know which radio stations have Net Promoter scores that are off the charts in our Techsurveys every year? Christian radio stations. That’s not a coincidence.

2. Articulate shared values and a shared purpose. My entire radio programming career was spent in the alternative rock format, where the broadcasters and the listeners shared a common purpose: to discover cool new music. At every radio station I worked at, we emphasized that purpose in our imaging production, and that constant reinforcement strengthened the bond not just between the listeners and our station, but between the listeners and each other.

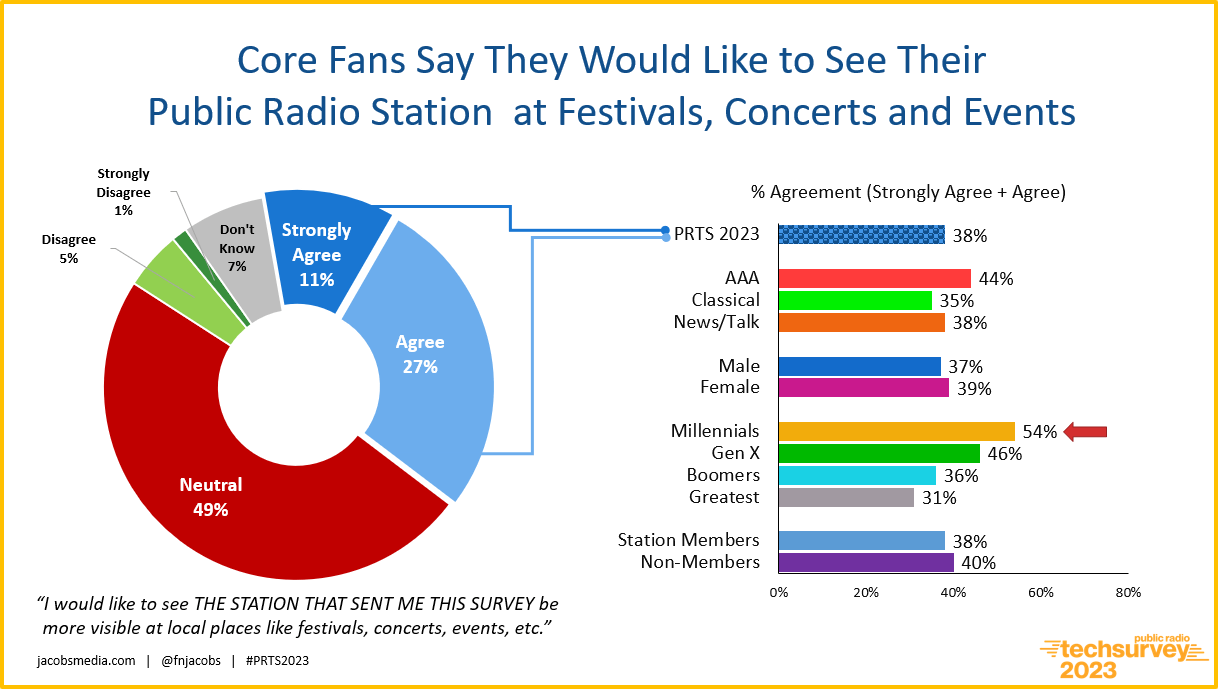

3. Cultivate spaces. Enable your listeners to interact with each other in person, online, or both through in-person events, virtual events, or online groups. Our new Public Radio Techsurvey that Fred is presenting today at PRPD in Philly underscores the importance of real eye-contact with a community. Note the spike for Millennials, an audience public radio programmers covet.

4. Define your brand in a way that helps people convey their social identity. If a listener is sporting your swag, they should be doing so with purpose.

5. Create boundaries. Create a ritual that provides a path for your audience members to become true community members. (That’s easier said than done, so I’ll elaborate in a future blog post.)

The final piece of advice comes from Carrie Melissa Jones, who highlighted the importance of showing audience members how they can become community members:

“If I were to advise the Parrothead community or Buffet estate, I would suggest finding more ways to bring outsiders like myself into the inside circle. As someone who is not a part of the community, I have no way of knowing what activities the community is engaged in, or how to get more involved. This lack of knowledge makes it unlikely that outsiders such as myself will become more involved and continue the existence of the Parrothead community in the long run.”

In other words, once you’re doing the things listed above, make sure you let the world know. Your airwaves are a great way to do that, a tool most communities don’t have.

If you’re interested in learning more about community building, I will be speaking on the topic at the NAB Show in New York City in October. I also highly recommend reading Mark Schaefer’s Belonging to the Brand, David Spinks’ The Business of Belonging, and Building Brand Communities by Carrie Melissa Jones and Charles H. Vogl. Thanks to all of the authors for weighing in on the Jimmy Buffet question!

- A Simple Digital Treat to Thank Your Radio Listeners This Thanksgiving - November 13, 2023

- Interview Questions When Hiring Your Radio Station’s Next Digital Marketing Manager - November 6, 2023

- A Radio Conversation with ChatGPT: Part 2 – Promotions - October 30, 2023

Great Article…..Great Connections…..Great Content Build Community. Thank you, Seth.

Glad you enjoyed it, Clark.

Creating a sense of place was a strong current that ran through our efforts. We did that with the understanding that our audience was looking for content that allowed them to connect with the world, to gain a broader understanding of the interconnectedness of issues, ideas, and events. It’s a community of people who are continuing seek something more. Something that came out of focus groups is our audience thought of us as a part of their continuing education. The sense of place is around shared values, more so than a geographic location.

Thanks, Kim!

I think you’re right, “connection” is the key word. Connection is what you want to happen in the spaces that you cultivate, and connection between audience members is what can’t be accomplished with content alone.

“Continuing education” is a great shared purpose, particularly for public radio, and appreciation for a particular place is a great shared value!

And then there are these people…

They just have to tell you:

—How many Bruce shows they’ve seen.

—How Cornell ’77 is the best Dead bootleg.

—They came close to buying a Kiss pinball machine.

—Their favorite Rush song is side one of ‘2112’

Parrot Heads?

Not even close to being that annoying.

They basically go out once a year and hit it pretty hard.

And they’re usually not at work the next day to talk about it…

Absolutely! Because there’s no clearly defined way for fans to see who belongs in the community and who doesn’t, people often try to “prove” that they belong on the inside. Everything you listed is an attempt to do this (and to imply that others don’t).

This makes fanbases different from other types of communities, where it’s very clear who’s in and who’s out.

The Grateful Dead indeed pioneered this approach. Coming from Motown, I was blown away working with them doing sound for a fans-only New Year’s Eve concert that was telecast to theaters.

Jimmy Buffet took it to another level by starting his own label. He actually hid his sales to keep them off the charts so he wouldn’t face as much competition. Garth Brooks stumbled into the Parrotheads with “Friends in Low Places” and the record industry woke up to what Buffet had done.

I’m not sure if Taylor Swift or her father is behind what all she’s done but it’s utterly amazing. Friends who recorded her have told me that every second she wasn’t singing or listening back, she was on Twitter with her “squad.”

Thanks, Bob! It’s great to hear the history from somebody who saw it up close!