I grew up in the Bay Area. As an angsty teen, one of my favorite things to do was to make a pilgrimage up to Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley and spend a day scouring the shelves of the music stores, like Amoeba and Rasputin’s. If you were lucky and thorough, you might find a CD from Sugar or Public Enemy in the discount bin. Often, it was worth it to shell out three bucks on a band that I only knew one song from; that was how audio discovery worked in the early 90s.

In the last ten years, I have heard a lot of discussion about “audio discovery” — and while some of that discussion has revolved around music, most of it has been about how people find podcasts. Within the podcasting community, there is widespread disagreement about whether or not the podcast space has a “discoverability problem.” There’s a good chance that where you stand on the issue depends on how big your podcast’s audience is. If your audience is small, you’re more likely to assume it’s because listeners haven’t discovered you yet. If only one of your audiograms went viral, surely the world would discover that you’re the next Joe Rogan.

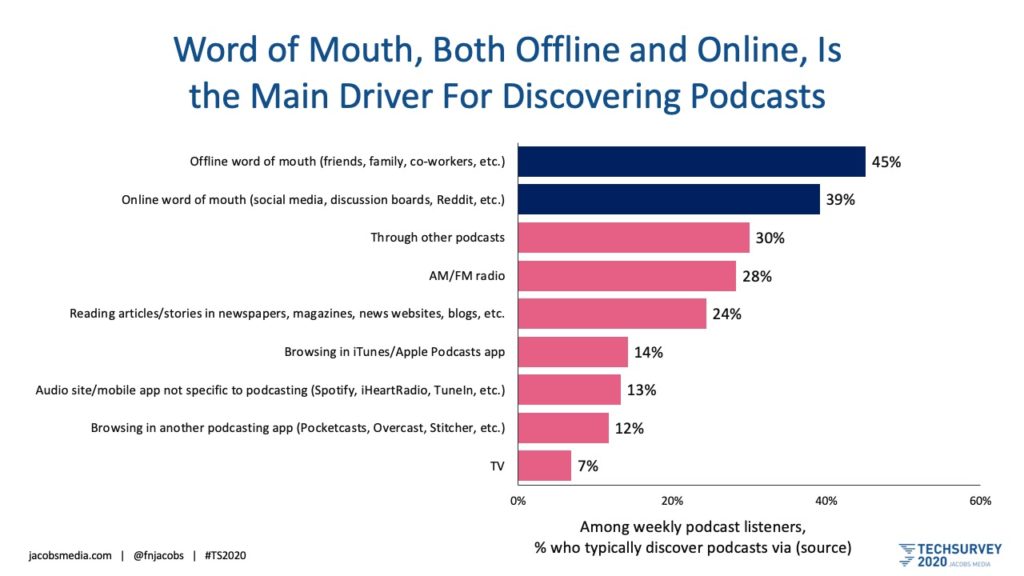

Last year’s Techsurvey shows that word of mouth — both online and offline — are the primary means of podcast discovery:

In the age of Google Analytics, “word of mouth” remains maddeningly difficult to define, let alone quantify or grow, leaving many podcasters frustrated.

Over the years, several entrepreneurial outfits have claimed to help listeners discover podcasts, though in reality, the goal has probably been to help podcasts discover listeners. After all, listeners don’t seem to be complaining that they can’t find enough compelling podcasts. If anything, there’s a glut of quality content out there.

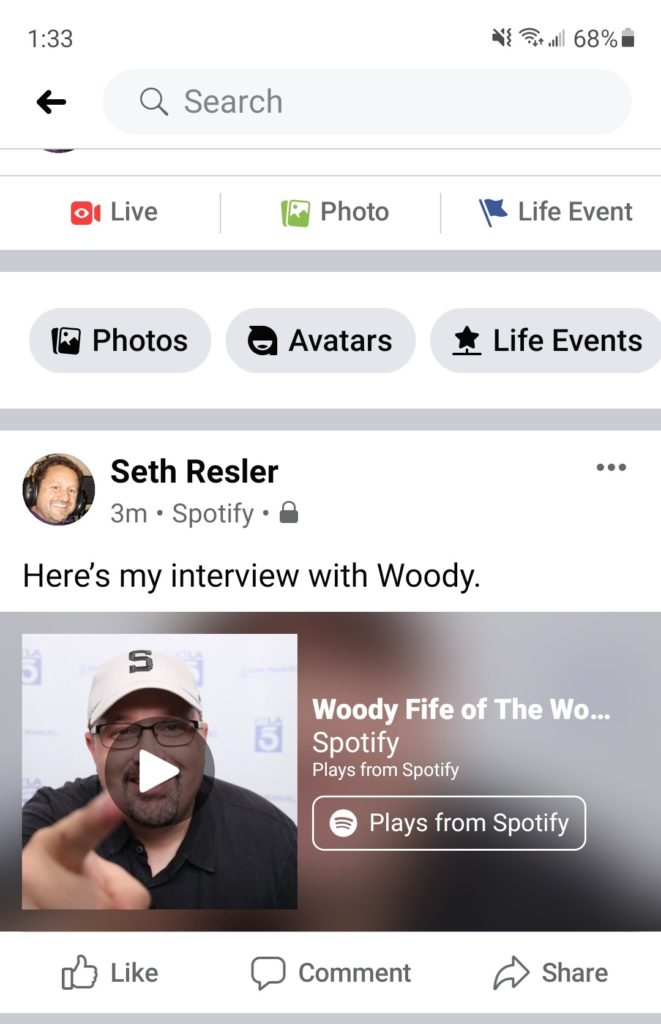

Facebook is the latest company to offer aid to those in need of help discovering promoting podcasts. The social network has teamed up with Spotify to offer a number of new tools for podcasters in the space, including and inline audio player for their newsfeed and the ability to turn audio snippets into short videos to make them sharable. But what’s going to make them succeed where so many other startups have not?

Content Discovery vs. Content Consumption

Too often, we make the mistake of conflating content discovery with content consumption, when they are in fact two distinct acts. It’s easy to see why we are prone to making this mistake in the digital age. There was a time when content discovery required a lot more effort. Just as I would invest time to shop for music in Berkeley, I used to spend hours in the library looking for books, or make a trip to Blockbuster to scour the shelves in search of a movie. Content discovery took a lot of work, and was not done at the same time as content consumption. After I found the perfect album or book or movie, I would take it home to consume it there.

The internet has changed that. Today, the acts of content discovery and content consumption happen almost simultaneously. I search for an article in Google, and I read it right away; I stumble across a TikTok video, and I watch it immediately; I browse through my Netflix recommendations, then hit play. We live in a world where content discovery and content consumption take place a split second from each other, so it’s easy to assume that they are the same action, but they’re not.

In fact, discovery and consumption are two distinct acts, and the difference has a significant impact on audio content in particular. Why? Because the act of audio discovery requires the use of your eyes, while the act of audio consumption does not. When I was poring over the bins in the Berkeley CD shops, I didn’t use my ears to discover music; I was reading album titles and looking at cover art. These visual clues helped me make my choices.

In fact, discovery and consumption are two distinct acts, and the difference has a significant impact on audio content in particular. Why? Because the act of audio discovery requires the use of your eyes, while the act of audio consumption does not. When I was poring over the bins in the Berkeley CD shops, I didn’t use my ears to discover music; I was reading album titles and looking at cover art. These visual clues helped me make my choices.

But when we consume audio, we don’t use our eyes. We’re almost always multitasking — listening to audio while we drive, work out, or clean the house, for example. Audio consumption allows our eyes to engage in another activity, while audio discovery does not.

This is notably different from the acts of text and video consumption, both of which require the use of our eyes. The ideal conditions for text or video discovery are the same as the ideal conditions for text or video consumption. Because we use our eyes for reading and watching, it’s much more likely that those actions will take place immediately following discovery. This makes it easier for companies like Google and Facebook to facilitate text and video discovery.

But audio is different. The ideal conditions for discovering audio are not the same as ideal conditions for consuming audio, because we want to use our eyes for the former but don’t want to use them for the latter. This means that under most circumstances, audio discovery is not immediately followed by audio consumption.

Yet almost every initiative to facilitate podcast discovery has mistakenly assumed that audio is like text and video, in that people want to consume it immediately after they find it. This may be the case if they’re searching in a dedicated audio app like Spotify, Soundcloud, or Audible. But nobody scrolls through their Twitter feed while standing in line at Starbucks, sees a link to a three-hour episode of Hardcore History, and starts listening right there. This is why audio doesn’t go viral.

(Several years ago, a racist voicemail message by the former owner of the Los Angeles Clippers did go viral. It’s notable that even though this content was audio in its original form, it did not go viral as audio; it went viral as a TMZ video. This illustrates how even on the rare occasions when audio does go viral, it goes viral as video.)

Given that audio discovery and audio consumption happen under difference circumstances, how can we facilitate audio discover? I see two ways:

1. Combining the Acts

There is one pre-internet device that has managed to make audio discovery possible with minimal use of your eyes. That device is the car radio, which comes with preset and scan buttons that make it possible to discover audio with little more than a few furtive glances at the dashboard. In doing so, the car radio made it possible to discover audio in a way that doesn’t prevent the listener from multitasking (driving).

There is one pre-internet device that has managed to make audio discovery possible with minimal use of your eyes. That device is the car radio, which comes with preset and scan buttons that make it possible to discover audio with little more than a few furtive glances at the dashboard. In doing so, the car radio made it possible to discover audio in a way that doesn’t prevent the listener from multitasking (driving).

But the car radio can only make this possible where there are a limited number of choices. I can scan through the limited number of radio stations in my city, or flip through my twelve station presets. But when there’s nearly two million podcasts out there, it’s impossible to sift through all the content without using your eyes.

One technological development, however, could enable listeners to discover audio without their eyes: voice commands. For example, you could be in your kitchen and ask Alexa to play jazz music without lifting your eyes from the pot of soup on the stovetop. If you don’t like the song that Alexa plays, you can request another. If you don’t recognize the song that you hear, you can ask for its name and title. This type of voice-command discovery is already happening and will continue to get refined for spoken-word audio, enabling listeners to ask for “the latest news about the pandemic” or “podcasts about soccer.”

In fact, searches initiated by voice command are likely to become so important to the discovery of audio content that an entire cottage industry around “audio search engine optimization” will spring up. Audio content creators will enlist experts who know how to ensure that their content is surfaced when commands are given to Alexa, Siri, Cortana, Bixby, or any other voice-activated operating system.

In short, one way to facilitate audio discovery is by focusing on voice commands which free up the eyes, enabling the end user to discover audio content under the same conditions that they consume audio content.

2. Separating the Acts

There is another way to solve the riddle of audio discovery: instead of trying to bring the acts of discovery and consumption closer together, double-down on their separation. Rather than trying to minimize the work that goes into discovery by making it more convenient, accept the fact that discovery happens under different circumstances. I relished my music-shopping adventures in Berkeley. I enjoyed them so much that I would set aside entire weekends for audio discovery. Finding the albums I wanted to listen to was half the fun!

Separating the acts of discovery and consumption requires embracing the visual component of audio discovery. Instead of trying to make discovery possible without eyes, make discovery a fun experience by providing a feast for the eyes. One way to do this is to turn audio excerpts into short videos. This is what audiograms, such as those made by Headliner or by Facebook’s new Soundbites feature, aim to do. Essentially, this serves the same purpose as album artwork, but whether a podcast’s audiogram can prove as compelling as the covers of Nevermind, Illmatic, or Dark Side of the Moon is an open question. (There’s also a parallel here between the way audiograms serve as a podcast discovery tool and TikTok videos serve as a music discovery tool.)

Another feature that could aid audio discovery is the ability to bookmark audio so you can listen to it later. Imagine standing in line at Starbucks, scrolling through your Instagram feed, and seeing an audiogram for Marc Maron’s interview with Will Ferrell. You’d like to listen to that conversation, but you’re not in the right circumstances at the moment. If only you could click a button that says “Save To My Playlist” so you could pull it up when you get into your car.

A bookmarking feature acknowledges that you’re not going to consume the audio at the moment of discovery. Instead, it allows you to save it and easily retrieve it to consume later.

I find myself doing this when I shop for audiobooks in the Audible app. I will invest time in the act of discovery with no intention of immediately listening to my selection. Instead, I will spend an hour reading the titles, descriptions, and reviews for books, and save a number of them to my wishlist. I may even make a purchase and download the audiobook, but I won’t actually play the audiobook until I set out on my long driving trip days later. It’s very similar to shopping in a real bookstore for a vacation read several days before going on a trip. The act of discovery and consumption are separate, and I enjoy them both in very different ways.

In other words, a second way to empower audio discovery is to keep the act of discovery separate and make that act enjoyable in and of itself, not just as a means to an end.

What Are Facebook and Spotify Doing?

Of all the aspects of Facebook’s new embrace of audio, I think the most interesting is the fact that the social network chose to partner with Spotify instead of trying to build its own audio platform. While there may be any number of reasons for this, it appears to recognize that while Facebook might be a good platform for discovering audio content, it’s not a good platform for consuming audio content. Spotify is much better suited to that. In essence, Facebook has chosen to pursue the second route outlined above.

But Facebook hasn’t gone far enough. Currently, Facebook’s new mini-player allows you to play audio from within your newsfeed, but does not allow you to bookmark it for later with a single click. If the company added this feature, it could do more for audio discovery than any device since the car radio.

In other words, Facebook and Spotify are probably closer to getting audio discovery in the digital age right than anybody so far, but they’re not quite there yet.

- A Simple Digital Treat to Thank Your Radio Listeners This Thanksgiving - November 13, 2023

- Interview Questions When Hiring Your Radio Station’s Next Digital Marketing Manager - November 6, 2023

- A Radio Conversation with ChatGPT: Part 2 – Promotions - October 30, 2023

Likin’ the bookmark idea. A lot!

Let’s hope an engineer at Spotify feels the same way.