The more we learn about AI and its potential to summarize and predict mountains of data, the more talk we hear about how the new technology might replace the science of conducting audience research.

Another term for this is “synthetic data,” and it’s gotten its share of oxygen in pockets of the research community in the past year or so. I blogged about this brave new world of consumer research last summer when news of an AI startup, Evidenza broke.

According to an AdAge story last year written by Adam Bai and Neil Dixit, Amazon Web Services defines this AI research platform as “non-human-created data that mimics real-world data.” The idea is to use AI science to create “synthetic personas” that can help brand managers – or radio program directors – predict behavior without enduring the time and expense of conventional research.

idea is to use AI science to create “synthetic personas” that can help brand managers – or radio program directors – predict behavior without enduring the time and expense of conventional research.

As I did in my blog, Bai and Dixit question the efficacy of this new dimension of data and behavior because of one key missing element:

The lack of qualitative data

That’s right – focus groups, one-on-ones, and ethnographic research studies. I’ve been doing this type of research throughout my entire career as an important partner to surveys (including audience ratings) that generate numbers but often lack the insights managers need.

The AdAge story is titled “Digital Twins – Why Qualitative Data Is Needed To Build Realistic Personas” – and it makes the case that unless you sit down and talk to real people, you miss a level of understanding you’ll never get from those “synthetic consumers.” For that matter, the seemingly simple task of listening to your customers will also reveal things you’d never glean from strictly statistics.

It is amazing – and scary – how often brand managers get so close to their product or service they miss out on the true insights that talking to actual people can yield. It is why whenever Jacobs Media is hired to conduct a quantitative project for a media brand, we will have a discussion with the client about the wisdom of conducting a couple of focus groups or a handful of one-on-ones with actual target users before delving into the creation of the questionnaire.

Not only do we as researchers gain useful information about the brand and the market, the client ends up learning, too. And incidentally, some managers are in denial about the true weaknesses of their brand and/or mitigating factors that might explain why success has been fleeting.

By skirting qualitative research and instead, going right to a quant study, all of the participants in the investigation process may find themselves missing an important piece of the strategic puzzle. And truly, the less you know about your audience, the more apt you’ll be surprised – OK, even gobsmacked – at what you hear from your small sample of real people.

We recently saw this in action in a project we conducted for The Bob & Sheri Show. The goal was to simply understand audience perceptions and behaviors. But never having worked for the show before, we elected to conduct a couple of focus groups on the front end.

We recently saw this in action in a project we conducted for The Bob & Sheri Show. The goal was to simply understand audience perceptions and behaviors. But never having worked for the show before, we elected to conduct a couple of focus groups on the front end.

That important first step helped us hear the words and phrases actual listeners use in describing a show many have been listening to for decades. It also gave us a chance to observe their emotions on display when fans talk about the show, its cast members, and what they represent to loyal fans. To say this initial qualitative step informed the subsequent questionnaire and our final analysis would be an understatement.

But it’s the quantitative piece that either confirms or muddies apparent learnings taken from the focus groups. Early in that questionnaire, we asked Bob & Sheri’s listeners to type in a word or two that first comes to mind when they think of the show – nothing more and nothing less – a true open-ended question with no listed choices for respondents to simply check.

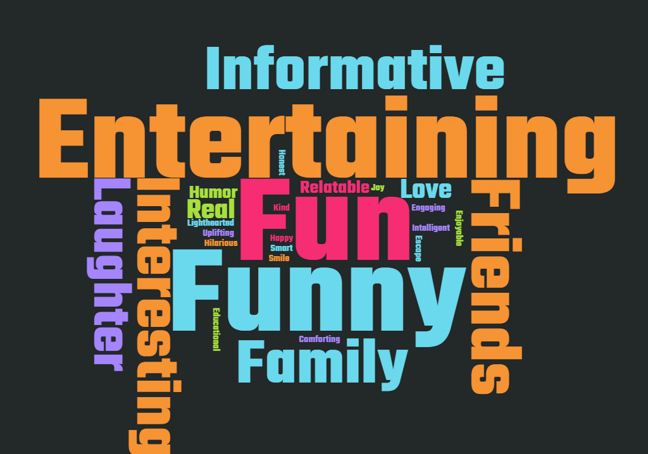

Given a robust sample of more than 1,000 respondents, we had a lot of data on our hands. And here’s where AI now comes into play with its ability to distill and calculate all those responses. The end result? A word cloud depicting the ways and degrees to which Bob & Sheri fans describe the show. The bigger the word, the more often it was listed as a response:

The show hoped for this type of graphic, especially the words “entertaining,” “fun,” and “funny” – attributes most radio ensembles like Bob & Sheri strive for.

But that next layer down is especially insightful, revealing descriptors even those inside the show might not have anticipated:

“Family” and “friends” jump off the word cloud, summing up attributes most shows dream of but often fail to attain.

For us at Jacobs, our process of “qualitative” first goes back to my formative years working for Frank Magid in Marion, Iowa. That’s where I learned not just how to moderate focus groups, but how to interpret and utilize this information.

Year later, we had a rare opportunity to raise our qualitative learning curve. In 2006, Arbitron hired us to conduct research to learn the terms young people were using to characterize their media habits. Dr. Ed Cohen was the mastermind, and he greenlighted a series of focus groups among teens and 18-34 year-olds.

They were eye-opening. The iPod was the gadget of choice during that period, although smartphones were becoming more commonplace, albeit without apps. Social media was still emergent, while consumers were beginning to make crude but popular (viral?) videos on a site called YouTube. It was the “wild west” period of this new millennium, and Dr. Ed knew his company was going to have to go to school on a variety of new terms, gadgets, and conditions in order to best connect with diary keepers.

I moderated all of these groups – and there were quite a few in multiple markets – but it was obvious to all of us that so much was changing, we were still behind the curve. And the fluorescently lit market research conference room with the two-way mirror was not conducive to learning what young people were actually doing when they were in their comfort zones.

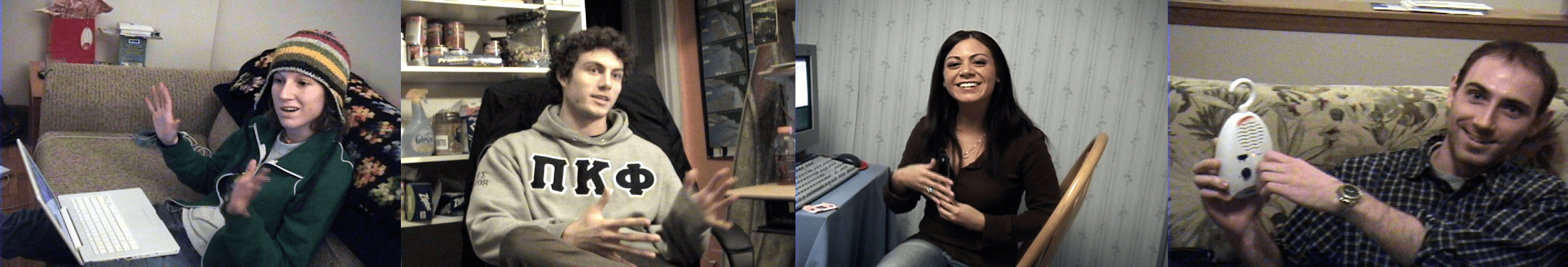

Ed found the money to design an “ethnographic survey” – the first of its kind for any radio client or organization that we knew of. The idea was to recruit 30 or so young people in select markets and arrange to spend the better part of day observing (and videotaping) how they “entertained and informed themselves.”

This ambitious initiative became known as “The Bedroom Project” and it turned out to be a qualitative mindblower. We hung out with the respondents in their homes, dorms, and apartments – and in their cars – watching them select the media and gadgets that suited them at any moment in time. And we later interviewed them – one-on-one – to do that deep dive to have them explain to us what they did and why they did it.

a qualitative mindblower. We hung out with the respondents in their homes, dorms, and apartments – and in their cars – watching them select the media and gadgets that suited them at any moment in time. And we later interviewed them – one-on-one – to do that deep dive to have them explain to us what they did and why they did it.

At the NAB/RAB Radio Show that fall, I had the honor of keynoting a “Super Session” to present the findings from “The Bedroom Project.” The presentation was 75% video montages and compilations of our young respondents in their natural habitats talking about their media habits. They didn’t know we worked in radio, and we allowed the conversation about media and gadgets to come to us. Radio came up when it came up – if at all.

When I tell you the crowd of 700+ that jammed into the convention ballroom to witness this presentation was riveted by these videos. Many were legitimately surprised by much of what they saw and heard – including that many of these respondents did not have an AM/FM radio where they lived.

(That finding inspired us to include that question in all our Techsurvey studies – an important barometer of broadcast radio’s eroding presence in people’s abodes.)

This is what happens when managers stare at spreadsheets and rankers, rather than listen to their “end users.”

“The Bedroom Project” turned out to be essential “data” for Arbitron and the radio industry that year even though there wasn’t a single chart or a graph in our deck.

We have since done other ethno studies, including one about mobile phones – “Goin’ Mobile” – designed and conducted in 2010. To this day, Paul and I talk about many respondents in these projects – by name. That’s the impression listening to real people can make.

But AI and large language models (LLMs) can and should play a role in the research we do on behalf of radio companies, as well as the studies you commission throughout the year.

Open-ended questions – a key to learning things you don’t know – can produce large bodies of information that are difficult to ingest and process. When we ask an open-ended question in Techsurvey, it produces literally thousands of responses – too many to accurately sift through and categorize.

Enter AI tools that can quickly and effectively convert this disparate qualitative opinions into useful and actionable information. As Bai and Dixit explain, this process leads to findings that can be turned into marketing tools.

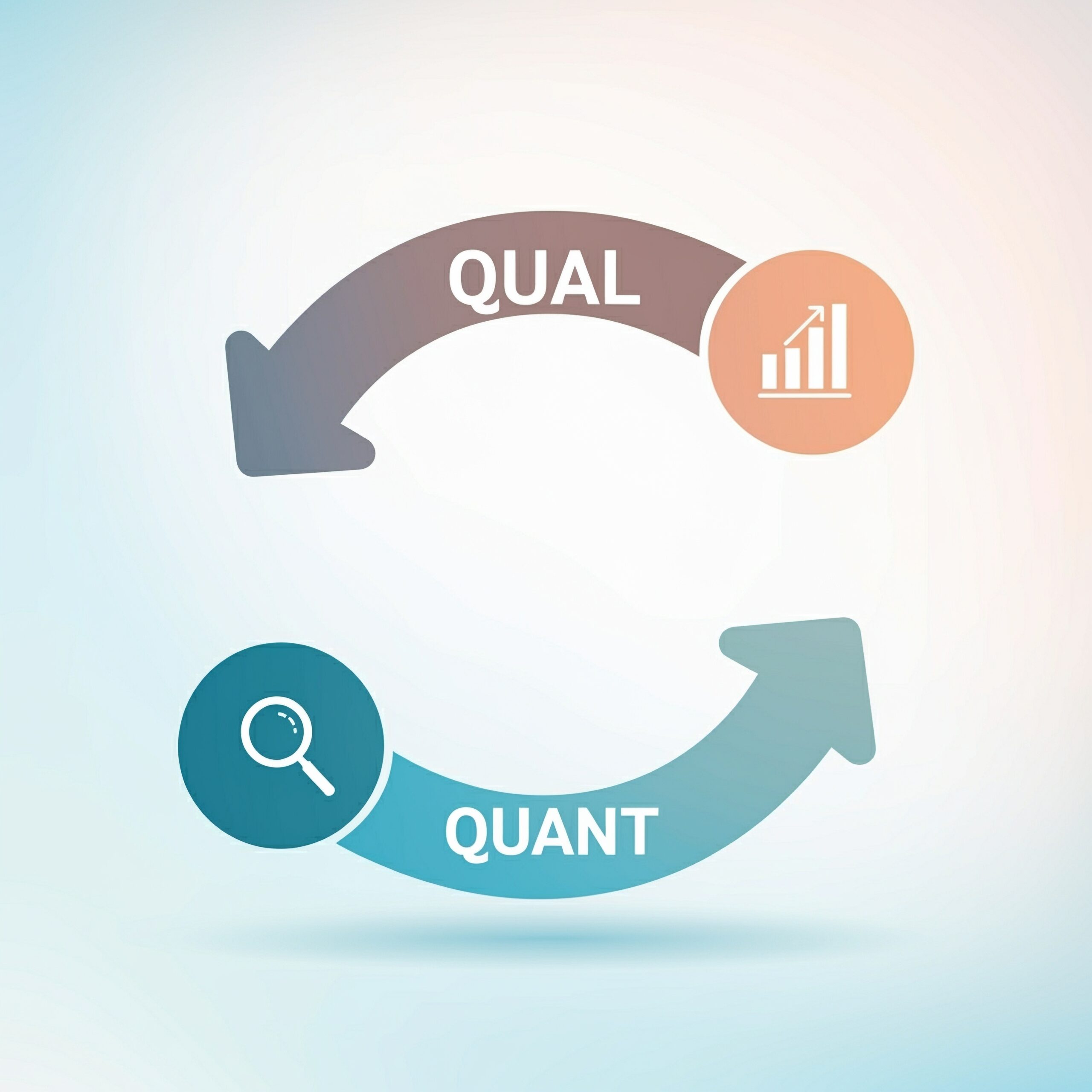

The Bob & Sheri word cloud is an example of converting a qualitative question into rich information where promos write themselves. The AdAge story paints the picture of a cycle: researchers start with qualitative, using AI tools to quickly and efficiently bring findings to the service. In this “holistic” process, they discover more of what they don’t know about their buyers (or in radio’s case, listeners).

When AI efficiently culls through reams of data to produce salient and timely information, it bridges that often troublesome gap between qualitative and quantitative research. When it’s properly applied, true understanding can be achieved.

applied, true understanding can be achieved.

AI cannot out-analyze humans with knowledge, experience, and perspective. But it can lessen the space between the “qual” and “quant” pieces, thus providing enhanced understanding.

Bai and Dixit refer to it as a “virtuous cycle,” where brands will be able to achieve rapid growth and success. That’s something to aspire to, particularly in an environment where brands often rush headlong in order to “ship,” missing key steps in the process.

Listen to your listeners.

Thanks to Tony Garcia for permission to use the Bob & Sheri data.

- “My Favorite Decade Of Music Is The __’s” - June 5, 2025

- Who’s Got It Better? Talent In Commercial Radio vs. Talent in Christian Music Radio - June 4, 2025

- It’s The Christian (Radio) Thing To Do - June 3, 2025

Leave a Reply