PRPD, the Public Radio Program Directors Association, recently teamed up with The Station Resource Group, Greater Public, and City Square Associates to produce a “Meta-Analysis of Local Research Studies.” In their words:

PRPD, the Public Radio Program Directors Association, recently teamed up with The Station Resource Group, Greater Public, and City Square Associates to produce a “Meta-Analysis of Local Research Studies.” In their words:

“[O]ur organizations compiled more than two dozen local audience research studies from stations across the country — from a variety of market sizes, geographies and broadcast formats — to perform a ‘meta-analysis’ that delivers actionable intelligence to a range of decision-makers by identifying common opportunities and threats for both [public] news and music stations.”

In short, they looked for common takeaways that emerged from a number of different research studies (some of which were conducted by Jacobs Media) to see what’s applicable to all public radio stations.

The resulting pair of reports make a fascinating read, and while all of the studies in question were conducted on public radio stations, there’s a lot in here that could also be applied to commercial radio stations. I highly recommend checking the reports out, and if you are headed to PRPD’s 2023 Content Conference next month in Philadelphia, City Square Associates will be presenting their research at the opening session.

I have taken a keen interest in the concept of “community” since the COVID-19 pandemic struck, so I was particularly intrigued when the reports highlighted community as one of the key themes that emerged in the research. In fact, the authors of the report they felt so strongly about the opportunity for radio that lies in serving the community that they singled it out in the introduction to the meta-analysis:

“While this report elevates a number of discrete themes and takeaways from these studies, something broader and more implicit emerges. Namely, for public radio to both survive and thrive in the near future, there will need to be a shift in mindset from a newsroom-driven or producer-driven approach, to one that focuses on serving the community as a whole.” [emphasis theirs]

Later in the same report, the authors underscore the importance that community plays not just on the programming side of the building, but also on the revenue side:

“A community-centered approach is not only essential to the development of prospective audiences but plays a key role in the future financial sustainability of the public radio industry as a whole.”

By the end of the report, the need to reimagine radio using a community-centric approach in both the programming and the revenue departments is taken as a foregone conclusion:

“Given the need to migrate from a producer-driven distributor of content to a community-centered organization with close ties to their local constituents, it would be worthwhile to further explore the relevance and appeal of specific alternatives to fundraising, and how the concept of ‘membership’ could be reimagined to include people new to public radio.”

All of this begs a question…

What do we mean when we say “community”?

The word “community” is never explicitly defined in either report, but it’s worth a closer look because it’s a word that broadcasters tend to toss around loosely.

I lurk in a lot of social media groups full of veteran broadcasters who frequently bemoan the fact that radio isn’t “live and local” anymore. They typically point to corporate consolidation and syndication as the source of radio’s decline, and prescribe a return to locally-focused content presented by local talent as a cure-all. I suspect many of these broadcasters would read this report and be tempted to think, “See? I told you so!”

This would treat the words “community” and “local” as synonymous, in which case the logical conclusion would be to ditch syndicated programming in favor of local on-air talent. I think this would be a mistake. If the answer to all of traditional media’s problems was simply, “produce more local content,” newspapers would be wildly successful right now. They’re not.

So if “community” doesn’t mean “local,” what does it mean?

Fortunately, in the last few years, we have seen the emergence of a number of books that explore this topic. David Spinks is the co-founder of CMX, a community of professional community managers. In his recent book, The Business of Belonging, he points out the fact that there isn’t common agreement on what the term “community” means:

“Community is a really broad term. If you ask a hundred people ‘What is community?’ you’ll get a hundred different answers.”

He then offers his favorite definition:

“The one theory that has always resonated most with me, and the one that has been most influential on recent research in the field of community psychology, is called the sense of community theory, created by social psychologists David McMillan and David Chavis in 1986.

The authors describe a sense of community as ‘a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together.’

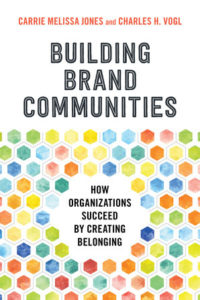

In Building Brand Communities, authors Carrie Melissa Jones and Charles H. Vogl provide a similar definition:

In Building Brand Communities, authors Carrie Melissa Jones and Charles H. Vogl provide a similar definition:

“[W]e define community as a group of people who share mutual concern for one another.”

(Both books then dive deeper by articulating different but strikingly similar lists of characteristics that communities have. I’ll let you read them on your own time.)

In short, a community is formed when its members feel a connection to one another.

Audiences are not communities

I have written before about the difference between an audience and a community and I’m not alone; Author Mark Schaefer dedicated an entire chapter to the differences between communities and audiences in his book, Belonging to the Brand. The difference?

Audiences are built around content. As broadcasters, speak to our audience members through our on-air and online content. The audience members can speak back to us, but not in a significant number. The audience members rarely, if ever, speak to each other.

By contrast, communities are built through spaces. Community members gather in these spaces, where they can connect with one another. These spaces can be physical (such as a conference hall, a church, or a swimming pool) or virtual (such as a Facebook group, a Slack channel, or a Discord server).

To build community, it’s not enough to create content; you must also cultivate a space that fosters connections between people.

A great example of a community is Podcast Movement, which is a community of podcasters seeking to improve their craft. Once a year, the organizers of Podcast Movement host a conference where podcasters can gather and connect with each other. This year’s conference takes place this week in Denver — and I’ll be hosting a discussion on community building there. But Podcast Movement has created more than just a once-a-year physical space; they’ve also cultivated a virtual space where podcasters can connect with their Facebook group, which has more than 80,000 members. (Podcast Movement Co-Founder Jared Easley gave a fantastic presentation at the NAB Show in Las Vegas earlier this year explaining how the organization grew this Facebook group.)

So if we are to heed the advice of the PRPD reports and reimagine our radio stations as community-centric organizations, the key question is not, “How can we produce more ‘live and local’ content?” The key questions is, “How can we build a space where people can connect with one another?” Producing local content may play a role in building that space, but local content alone is not going to get the job done.

The problem with subscription content

Over the last decade, we have seen the rise of subscription content models, led by streaming services like Netflix and Hulu. Many broadcasters, especially those in public radio and podcasting, viewed this as ray of hope: perhaps we can generate revenue by putting some content behind a paywall.

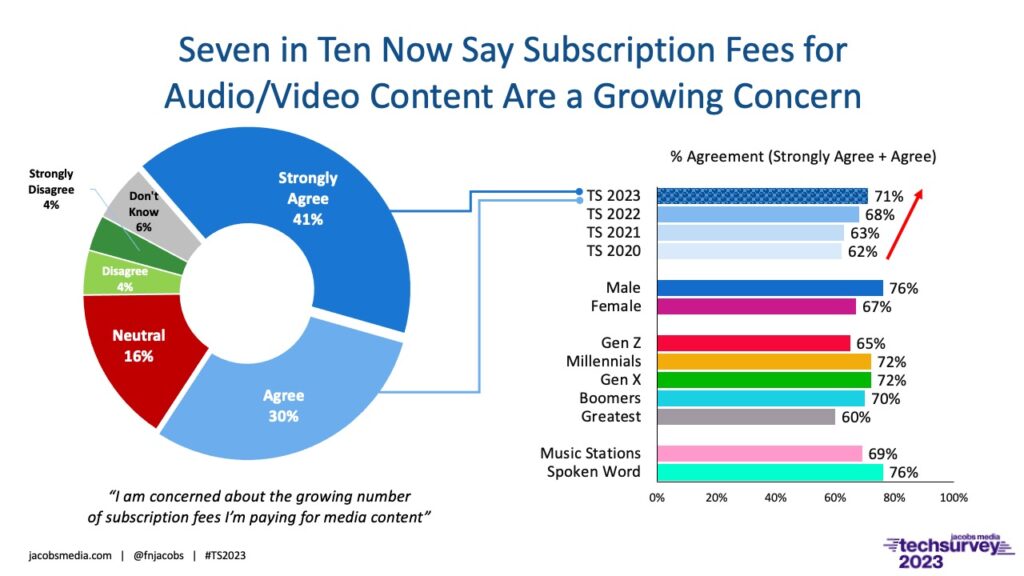

However, as we’ve seen in our annual Techsurvey, radio listeners are increasingly concerned about their subscription fees:

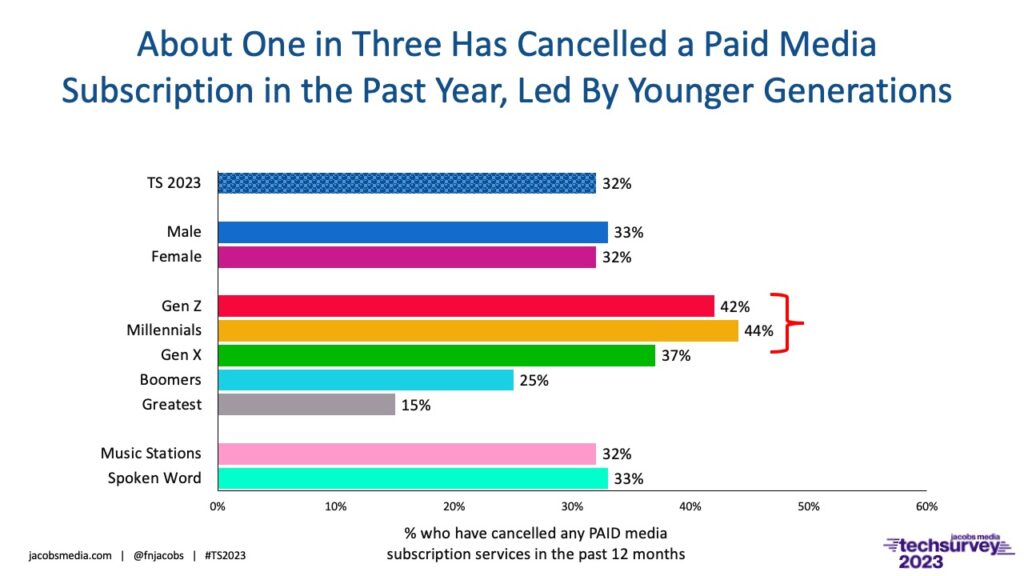

In fact, we are starting to see listeners cancel content subscriptions:

(Note: These results are from Techsurvey, which surveys commercial radio listeners. To find out how public radio listeners feel about subscriptions, go to Fred Jacobs‘ session at PRPD next month, where he’ll debut the results of the 2023 Public Radio Techsurvey.)

Getting people to pay for content works when that content is exclusive, scarce, and highly valued by the audience: Think Star Wars, Star Trek, or Pixar. When the content is not scarce, it becomes harder to entice people to pay for it — a lesson that Marvel is learning as a glut of superhero movies and TV shows is giving rise to audience fatigue.

The scarcity issue presents a particular problem for linear broadcasters, who are already producing 24 hours of content each day. As an example, let’s take a look at…

The Case of CNN+

CNN+ was the cable news network’s short-lived attempt to create a subscription service featuring content not found on its regular cable programming. There are lots of reasons why CNN+ failed, not the least of which was due to internal politics. But even without those issues, I don’t think it would have succeeded for one very simple reason: CNN content is not a scarce resource. Anderson Cooper, Wolf Blitzer, and Sanjay Gupta are some of the best at what they do, but they are already producing more content than I could ever possibly consume. Why would I pay for more Anderson Cooper when I haven’t watched all the Anderson Cooper that I’ve already got?

CNN+ was the cable news network’s short-lived attempt to create a subscription service featuring content not found on its regular cable programming. There are lots of reasons why CNN+ failed, not the least of which was due to internal politics. But even without those issues, I don’t think it would have succeeded for one very simple reason: CNN content is not a scarce resource. Anderson Cooper, Wolf Blitzer, and Sanjay Gupta are some of the best at what they do, but they are already producing more content than I could ever possibly consume. Why would I pay for more Anderson Cooper when I haven’t watched all the Anderson Cooper that I’ve already got?

I believe there’s an alternative universe where CNN+ is a wild success. In this universe, not only is Richard Reed played by Jim from The Office, but CNN+ put its community behind the paywall, not content.

In this universe, CNN says, “If you want to watch Stanley Tucci and Anthony Bourdain show you places to eat when you travel, just watch our regular cable channel. But if you want to connect with other foodies who plan their travel around culinary destinations, join the CNN+ community. In this community, you can ask questions of and swap tips with other traveling foodies.” (In this universe, Chris Wallace and Audie Cornish also run a Michelen star restaurant.)

One audience, multiple communities

While media entities tend to think of themselves as having one large audience, they may need to foster multiple smaller communities. Obviously, not everybody who watches CNN is a traveling foodie, so the network may also want to create spaces for people who want to bond over news about sports, pop culture, news from particular geographic regions, and more.

By the same token, you can imagine a brand like Nike building not just one community for Nike fans, but rather distinct communities for basketball players, marathon runners, sneaker collectors, etc. These communities will organize around a shared sense of purpose among the members, not just geographic proximity.

The same will be true for radio: A station’s audience can give rise to multiple communities focused around different interests, from parenting to craft beer to the local professional soccer team. Just as only a small percentage of the audience becomes public radio station donors, only a small percentage will participate in the station communities. But that small percentage could generate a significant stream of revenue…

Community subscriptions, not content subscriptions

When we talk about reimagining public radio membership as a community-centric venture, what we’re really saying is: Build spaces for communities, and put access to that space behind a subscription paywall.

Commercial and Christian radio could also put this model into practice and develop a new stream of revenue. Here’s an example of how that could work for a rock radio station.

Paywalled communities do raise questions about equitable access, particularly for public radio, which does not want to be a resource that is only available to those with enough money. Those concerns are valid and need to be addressed, but I don’t think they present an insurmountable obstacle.

The future is in community

I believe that the meta-analysis report from PRPD and friends is correct: The big opportunity for radio stations to thrive lies in shifting from a content-first (or “producer-driven”) mindset to a “community-centric” mindset. That shift requires recognizing that communities can’t be built on local content alone. What we’re talking about is much more than just “live and local” radio.

For more on this topic…

Podcast Movement takes place this week in Denver. I’ll be hosting a discussion about community building, as well as my annual “Podcast Makeover” session.

PRPD’s 2023 Content Conference takes place September 21st through the 23rd in Philadelphia. City Square Associates will speak about their meta-analysis, and Fred Jacobs will debut the results of Public Radio Techsurvey 2023.

If you’re not in public radio, I will be speaking about community building at the NAB Show in New York in October.

- A Simple Digital Treat to Thank Your Radio Listeners This Thanksgiving - November 13, 2023

- Interview Questions When Hiring Your Radio Station’s Next Digital Marketing Manager - November 6, 2023

- A Radio Conversation with ChatGPT: Part 2 – Promotions - October 30, 2023

Leave a Reply