Two years isn’t that long ago. But in COVID time, it feels like eons. Shortly after the pandemic hit American cities, and the lockdowns began, brother Paul took to the keyboard to suggest some action steps for the sales department. Like reading an old diary, it’s a fascinating look back at what happened, what didn’t, and what might have been.

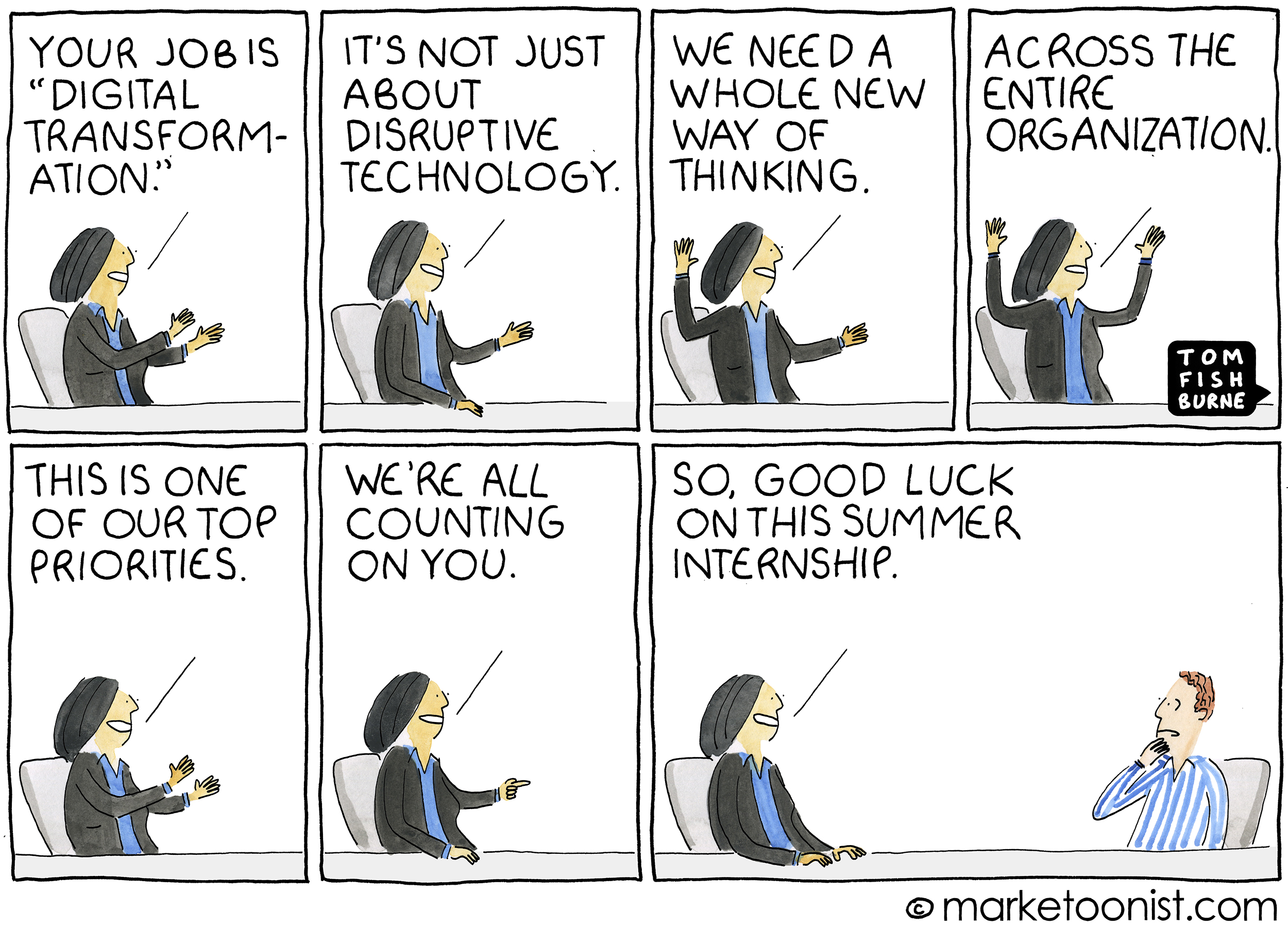

I have heard many people lament the things that radio coulda and shoulda done during the COVID that may have materially changed our industry post-pandemic. Did we let a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity go wasted?

On the programming side of the aisle, personalities, PDs, IT experts, and engineers immediately jumped into the fray, fighting ways to technically and realistically “work from home.”

On the sales side, change came slower. Most immediately started making calls from their kitchens and spare bedrooms. But two years gone, and what has changed about the ways in which radio stations position, sell, and market themselves?

There may be debates about it – always a good thing. But when you read Paul’s perceptive post below, I think it will make many pause and think about not only what happened, but what could have been. – FJ

“How Radio Can Turn ‘Lemons’ Into Lemonade” by Paul Jacobs, April 2020

Growing up in Detroit in the 1960s, we always looked forward to September, when the new car models made their glitzy debuts. We used to walk around the new lots at neighborhood dealerships, checking out the latest and greatest that came out of the factories of the Motor City and in factories in and around the state of Michigan. From our inbred, narrow perspective, Detroit made the best cars around, and at the time, we were right.

Of course, back then, there wasn’t really much in the way of competition. The result turned out to be American cars designed with “planned obsolescence” – in other words, vehicles that weren’t built to last, frequently rusting out, and even breaking down after just a couple years. The worst of these were nicknamed “lemons,” a euphemism for cars that were losers or just plain sucked.

The problem became so common that some states passed “lemon laws,” designed to protect consumers from being stuck with poor performing Chevy Vegas and also those flawed Chrysler K-cars that were simply defective the day they left the showroom and drove off dealer lots. Despite their dubious quality, Detroit kept selling a lot of cars, because what came off those Big 3 assembly lines were the only available choices most Americans had.

All of that changed in an instant in the early 70s, when the oil embargo hit the U.S. and gas prices skyrocketed. All of a sudden, American consumers woke up to the fact their cars not only were substandard, they were “gas guzzlers” – many getting less than 10 miles a gallon. That wasn’t problematic when gas was 15¢ a gallon. But when prices hit a dollar – and more – consumers began looking around for a better deal – and more efficient cars.

All of that changed in an instant in the early 70s, when the oil embargo hit the U.S. and gas prices skyrocketed. All of a sudden, American consumers woke up to the fact their cars not only were substandard, they were “gas guzzlers” – many getting less than 10 miles a gallon. That wasn’t problematic when gas was 15¢ a gallon. But when prices hit a dollar – and more – consumers began looking around for a better deal – and more efficient cars.

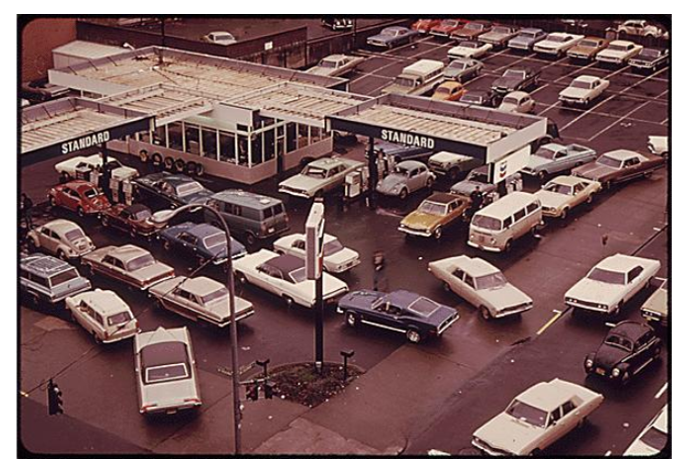

In 1973, the “oil crisis” as it was called back then, spawned long lines at gas pumps all over America. If you think it’s challenging to buy toilet paper now, sitting in a running car in a seemingly endless line to overpay for gas was no party.

Many found the solution not in Detroit, but in Japan. While the early models from Datsun (now Nissan), Toyota, and Honda left something to be desired and weren’t very stylish, they solved the biggest complaints consumers had – they got great gas mileage and they were competitively priced.

And out of a crisis, the auto industry changed forever.

Detroit’s Big 3 automakers had to rethink everything, from design to engineering to the dealer experience. Thankfully, they eventually got around to  retooling from top to bottom, but they never recaptured the historical dominance they enjoyed in the 50’s and 60’s.

retooling from top to bottom, but they never recaptured the historical dominance they enjoyed in the 50’s and 60’s.

Their weaknesses, borne out of a lack of competition and an excess of hubris and arrogance, became exposed. In time, foreign automakers built factories in America, becoming part of the fabric of the U.S. economy. And today, while Ford, GM, and (Fiat Chrysler) cars more than hold their own, vehicles from Japan, Germany, and South Korea make up a huge share of the market.

Fast forward to today’s COVID-19.

A recent article in Media Insider from Dave Morgan, “TV Must Retools Now: Lessons Not Learned By US Automakers In The ‘70s,” brought all those memories back to me in a V-8 rush. While Morgan focuses on the television business (which arguably is in worse competitive shape than radio), the lessons are universal.

He summarizes Detroit’s big vulnerability this way: “U.S. automakers never returned to the kind of market share and consumer loyalty they had pre-1970. Why? Because they were so in love with their own products, they had long since stopped worrying about their consumers’ problems: boring cars that were expensive to drive, rusted out, broke down, and had to be replaced every 3-5 years.”

He summarizes Detroit’s big vulnerability this way: “U.S. automakers never returned to the kind of market share and consumer loyalty they had pre-1970. Why? Because they were so in love with their own products, they had long since stopped worrying about their consumers’ problems: boring cars that were expensive to drive, rusted out, broke down, and had to be replaced every 3-5 years.”

In many ways, the radio broadcasting business here in America has held up much better than the Big 3 in the latter stages of the 20th century. Despite a torrent of new competition these past couple decades, radio’s overall reach and cultural impact has held up surprisingly well.

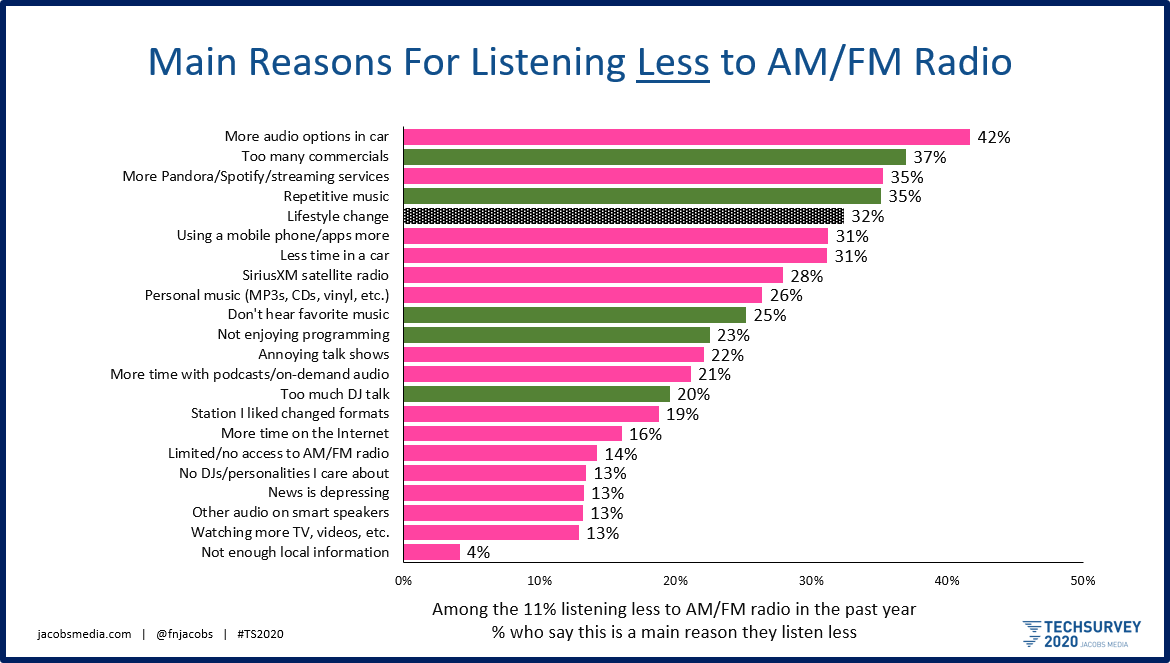

But among younger consumers, in particular, radio has challenges it has failed to overcome or address – some of which are self-inflicted. We see this slow leak in our Techsurveys – conducted among radio fans – with each passing year. Many radio stations are tagged with having excessive spotloads, tiresome music repetition, and bland, predictable programming.

Yet, broadcasters often turn a blind eye to digital competitors, in much the same away the Big 3 ignored Japan. A case in point? In perceptual research conducted by some of the biggest and best companies, it is still a screen-in requirement that respondents are regular AM/FM radio listeners. That would be akin to GM, Ford, and Chrysler commissioning research in the 70’s that excluded Japanese car buyers. Ultimately, you see what you want to see. And as a result, some of broadcast radio’s congenital problems remain, unaddressed year after year. In the meantime, consumer perceptions take hold, making it ever so difficult to get this audience back.

That’s why events of the past two months are so telling. Since COVID-19 hit the U.S., many radio stations have done themselves proud. Some of the best have not only provided important local information, but they’ve been supportive of local businesses, organized food drives, and provided support to frontline workers, including healthcare professionals, waitstaffs from local restaurants, and more. During this phase, some broadcasters have truly demonstrated the importance and benefits of live and local.

So, let’s assume for a moment this pandemic can be the same sort of seminal moment for radio as the energy crisis was for Detroit automakers. But, instead of enduring a decade or more of incredible economic pain suffered by the Big 3, broadcast radio began planning now for a new, more customer focused, robust future.

As Morgan explains, “It took bankruptcies, the losses of millions of jobs and enormous customer defection until automakers grudgingly retooled, created new products, adopted true quality controlled production, and global supply change.”

I’d like to think radio’s leadership is smarter than that.

Prior to the pandemic, some of radio’s biggest broadcasting companies have faced bankruptcies, flat revenue growth, and significant layoffs. Plus, the competition is now well-developed – SiriusXM, Spotify, podcasts, and more frequently earn bigger slices of the audio pie. So, the case can be made that it’s imperative the radio industry take this unique, game-changing opportunity to retool and emerge stronger and more competitive as the pandemic fades, and hopefully, is in our collective rear-view mirrors.

To that end, here are a few suggestions (and I welcome others), inspired by Morgan’s analysis and my observation of the industry from Jacobs Media’s unique vantage point:

“Live and local” needs to be more than a slogan. It’s the lifeblood of the industry. Radio needs to recapture its hometown zeitgeist – not just during the pandemic but 24/7/365. And it starts with developing, embracing, and empowering its talent. This is the singular benefit of broadcast radio that cannot be replicated by digital competitors, and as the global pandemic has reminded us, people care a lot more about what’s happening in their hoods than what’s going down in Wuhan or Wales.

Radio sounds better with fewer commercials. Let’s keep it that way. As a sales guy, it pains me to hear about the cancellations stations have endured. But as a listener, stopsets are shorter, and the listening experience is significantly better. Broadcasters have a unique window to rethink clocks, avails, inventory, and pricing. A commitment to a leaner commercial load will not  only help stations sound better, but with reduced inventory rates might actually start increasing. One can only hope.

only help stations sound better, but with reduced inventory rates might actually start increasing. One can only hope.

Stop selling just the terrestrial audience. Our COVID-19 research shows the ways in which consumers are listening to the radio since being homebound are changing. They are spending less time in the car and at work, and more quarter hours at home, where apps, smart speakers, and laptops have taken the place of radio “receivers.” Yet, increased listening via the stream is either not being measured or marketed with any degree of emphasis or expertise. These are the same “ears” your sales staff uses from Nielsen ratings.

Digital shouldn’t be devalued. In fact, it’s a proof positive that so many brands are making the transition to digital distribution. Why should it matter to an advertiser if a consumer hears their ads on the air or in an app? It’s time to take a holistic approach to audience delivery, and begin to optimize the value of a station’s total reach and connection.

Beasley’s Chief Digital Officer, Todd Handy, recently pulled a key quote from WARC’s newsletter, a summation of the COVID-19 world of marketing:

“What it boils down to is a clear illustration of why digital transformation is not a nice-to-have anymore; it is now keeping businesses afloat.”

Yet, how many broadcasters have truly elevated digital content creation, sales, and marketing to the level it deserves. As we’ve seen since the coronavirus pandemic has droned on, more and consumers are turning to digital distribution outlets – their phones, laptops, and smart speakers – to access their favorite radio stations. Hopefully, this event signals the end of digital being the red-headed stepchild of radio programming and sales.

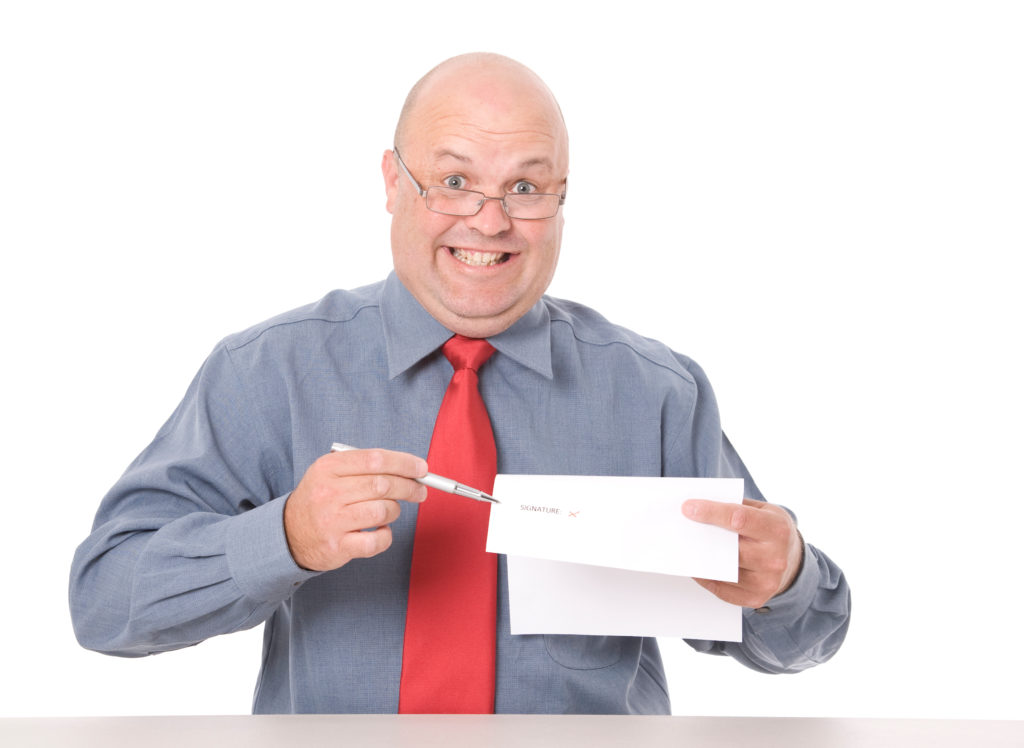

Simplify the media buying process. If I can buy a car or a pizza online, each customized to my specifications, and delivered to my doorstep, why can’t an advertiser buy an ad schedule online? If Google, Facebook, and others can make it dirt simple for any small business person to access and use their vast marketing platforms, why does broadcast radio make it so difficult? It’s time to elevate and streamline this process, because the simpler and more DIY it is, the more money will flow back into radio, especially post-COVID.

As President John F. Kennedy often said when he was running for the nation’s highest office in 1960, a crisis cuts both ways.

Decades ago, it took Detroit carmakers way too long to respond to the gas crisis, and the fallout that ensued. The result was economically devastating here in Michigan for years and years.

Today, radio finds itself in a similar position. An existential crisis is slamming the advertising environment in ways that were unimaginable back in February. So, why let a perfectly good crisis go to waste? Why not use this opportunity to reinvent and reinvest in what makes radio great and vital, so the industry can emerge stronger from the pandemic?

Please pass the lemonade.

- The Revolution Will Not Be Monetized - December 30, 2024

- What Kind Of Team Do You Want To Be? - October 4, 2024

- The Revolution Will Not Be Monetized - August 20, 2024

Taking the auto-industry analogy further, what would’ve happened if the non-Big Three companies sorted themselves out differently during the ’50s? It might’ve been only during the post-WWII era that GM, Ford, and Chrysler came to truly dominate the industry–with many of the other firms that had survived the War resorting to mergers to try to stay competitive (especially in light of a price war in the early ’50s).

The main example was AMC being created by merging Nash and Hudson–although both Studebaker and Packard were also courted. (Those latter two firms themselves merged, but Studebaker’s growing issues ended up sinking that combined company.) Likewise, the company that would eventually be known as Kaiser Jeep was created through a few other deals–and quickly realized that Jeep was much more successful, resulting in the company dropping its passenger-car lines. For many years, while perhaps never prospering financially, the scrappier AMC was able to innovate and focus on smaller cars–and ended up purchasing Kaiser Jeep in 1970.

Even though most folks (including myself) are more familiar with the AMC of the ’70s and ’80s (leading up to its purchase by Chrysler), all of this is a roundabout way of me saying that maybe there are some lessons to be learned (including for radio) from the early AMC and Kaiser Jeep.

(Thanks, Wikipedia!)

The Jeep story is a fascinating one, including how the brand helped Chrysler through the Daimler mess, and continues to be one of its brightest stories today. There’s a lot to be said about nurturing and investing in a heritage brand. When you consider the Jeep spinoffs, like Compass and now the return of the Wagoneer, these moves show you the importance of brand depth. Thanks, Eric.